Astroturfing: How Hijacked Accounts and Dark Public Relations Faked Support for China's Response to COVID-19

Overview

In 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a network of accounts on Twitter, which had previously posted narratives friendly to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), switched their messaging to focus on the pandemic, attempting to portray government actions in response to the pandemic in a more positive light. The accounts, many of which exhibited the hallmarks of automation and inauthenticity, were also linked to a public relations firm in China, indicating they may have been created and operated by the company. This case study, written by ProPublica’s Jeff Kao, a computational journalist and data scientist, breaks down this campaign, highlighting the various tactics and network terrain used and the pro-CCP narratives that were seeded.

STAGE 1: Manipulation Campaign Planning and Origins

Because of the limited amount of evidence, it is difficult to ascertain with certainty who the operators of this network and the origins of the campaign. However, based on a number of indicators later revealed through an investigation conducted at ProPublica, this network of pro-Beijing accounts was likely operated by a Beijing-based social media consulting firm who had been contracted to do this work. This determination was made based on multiple indicators. First, the existence of a 2019 contract between the public relatitons company OneSight (Beijing) Technology Ltd. and China News Service (CNS), a state-owned news agency, to increase the Twitter following of CNS.1 Second, close parallels in content and tactics between this network and influence operation accounts previously banned by Twitter and linked to China (further explained below). Third, the network conducting the campaign was also found boosting the Twitter account of the PR company, as well as the Twitter accounts of CNS and other Chinese state media, such as Xinhua and People’s Daily. OneSight declined to comment and CNS did not respond to inquiries by ProPublica.

- 1“Source Document Contributed to DocumentCloud by Jeff Kao (ProPublica),” accessed March 10, 2021, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6817072-0714中标公告-1.html.

STAGE 2: Seeding Campaign Across Social Platforms and Web

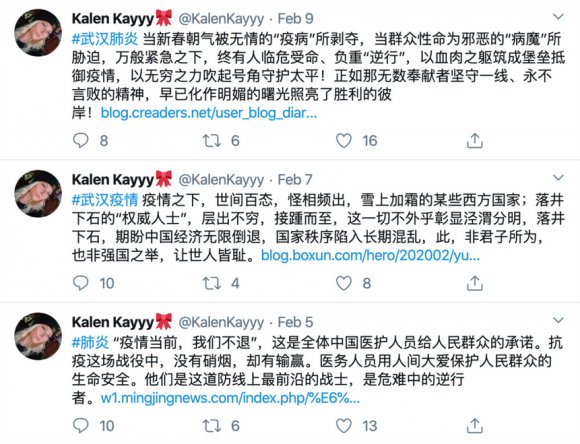

At the start of the coronavirus outbreak in December 2019, a Twitter network of at least 2,000 accounts was posting content in the interest of the CCP, such as disparaging political opponents and criticizing the pro-democracy protest movement in Hong Kong. But as the Chinese government acknowledged the situation in Wuhan in late January 2020, some of the accounts quickly switched their focus to the active crisis, and the epidemic became their main concern. Figures 1a and 1b below compare one of the accounts’ posts prior to and after COVID-19 started spreading across the globe.

The network exhibited a pattern where central accounts were amplified by other accounts in the network through likes, retweets, and replies that were often lifted directly from state editorials (see figure 2 below).1 Notably, the central accounts had relatively richer profiles (i.e., a wider diversity of posts, a longer history, plausible names and profile photos, and realistic friends and followers), and in some cases, had been hijacked from real users. In contrast, the amplifier accounts were far less detailed, and, due to the volume and coordinated nature of their activity, are likely to be automated. In total, over 2,000 accounts were identified as clearly belonging to this network based on their content, patterns of posts, retweets and likes.

- 1 Jeff Kao and Mia Shuang Li, “How China Built a Twitter Machine Then Let It Loose on Coronavirus,” ProPublica, March 26, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/how-china-built-a-twitter-propaganda-machine-then-let-it-loose-on-coronavirus?token=6gUgP8l5cJIpT-zNaKZUM1en4qd5mMoT.

Overall, the messaging was primarily written in simplified Chinese and traditional Chinese. These messages appeared to be aimed at Chinese-language Twitter users in China and the diaspora, cheerleading the CCP’s response to the pandemic. For example, common messages repeatedly shared by the network celebrated health workers as heroes and martyrs, called on people to support the government in fighting the outbreak, and sought to dispel “rumors” about the situation in Wuhan on social media. In addition to the coronavirus and Hong Kong, the network also disparaged the exiled political dissident Guo Wengui, a billionaire with ties to Steve Bannon.1 The content of these posts paralleled those found in datasets of Chinese state-backed accounts released by Twitter in 2019 and 2020.2

However, there was also content posted in English that sought to bolster the government’s image abroad and highlight its mask diplomacy, China’s aid of medical supplies to other countries around the world.3

The network contained a mix of manually created content and automated posting and boosting by . For example, identical tweets would be repeatedly posted to different central accounts, and automated amplifier accounts would engage with them in the same way, leading to similar reply, retweet, and like metrics for those posts (see figure 3 below). This automated activity also made it possible for researchers, like ProPublica, to crawl the network of centrally controlled accounts and identify other accounts benefiting from this false engagement.

- 1Amy Qin, Vivian Wang, and Danny Hakim, “How Steve Bannon and a Chinese Billionaire Created a Right-Wing Coronavirus Media Sensation,” The New York Times, November 23, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/20/business/media/steve-bannon-china.html.

- 2Twitter Safety, “Disclosing Networks of State-Linked Information Operations We’ve Removed,” Twitter, June 12, 2020, https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2020/information-operations-june-2020.html.

- 3Brian Wong, “China’s Mask Diplomacy,” The Diplomat, March 25, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/03/chinas-mask-diplomacy/.

These accounts also sometimes used hashtags, for example, #武汉真相 (#wuhantruth) and #香港暴徒 (#hongkongrioters) in an attempt to boost certain messaging and insert themselves into conversations around trending topics such as the coronavirus outbreak or the Hong Kong protests, as seen in figure 4 below.

Another tactic was the use and reuse of pre-approved comment banks, aka copypasta: short snippets of text that can be reused, off-the-shelf, to reply to posts quickly. Posts with original content in the network were often accompanied by canned replies from a number of inauthentic accounts -- i.e. accounts with thin profiles and repetitive patterns of posting. The comment texts were often lifted word-for-word from state media editorials and the same comments were used over and over.

Sometimes hijacked central accounts would launder their profile by changing their display name and username, or by deleting old posts that would indicate a user’s past history (see figure 5 below). It is unclear whether the were originally hacked by Chinese government affiliates, or purchased on the secondary market.1

- 1See, e.g., Nicholas Confessore et al., “The Follower Factory,” The New York Times, January 27, 2018, sec. Technology, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/01/27/technology/social-media-bots.html, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/01/27/technology/social-media-bots.html.

Although it is difficult to attribute with certainty, the network bears striking similarity to Chinese government influence campaigns unmasked by Twitter in 2019. Both networks contained a pattern of coordinated activity that appeared to be aimed at building momentum for particular posts. As with this network, central accounts would post a political message, meme, or a provocative video, for example, and a network of shallow supporting accounts would engage the content with likes, retweets and positive comments, presumably to boost their algorithmic visibility.

STAGE 3: Responses by Industry, Activists, Politicians, and Journalists

It appeared that this ostensibly false activity was intended to generate an illusion of grassroots support for the Chinese government and its positions — in other words, astroturfing. Certain fake accounts in the network were picked up and amplified by traditional media reports, particularly Chinese state media, and Hong Kong media with a history of pro-government positions. The most prominent fake account in this network to be boosted was “Amanda Chen,” a Twitter account claiming to belong to the wife of a Hong Kong policeman with thousands of followers. Its posts had previously attracted attention from pro-Beijing media during the 2019 protests such as Sing Tao Daily, and government outlets such as Southern Metropolis Daily.1 The persona was continually suspended by Twitter for suspicious behavior during 2019 and 2020, but would soon reappear under a different account name with thousands of followers. ProPublica has found this account being boosted by the same propaganda networks, but hasn’t been able to find any independent evidence that Amanda Chen actually exists.

- 1 Southern Metropolis Daily, “Hong Kong Police Sister’s Diary,” STNN.CC, September 22, 2019, http://m.stnn.cc/pcarticle/673569; Southern Metropolis Daily, “‘Hong Kong Police Sister’s Diary’ Replied,” Sohu, September 21, 2019, www.sohu.com/a/342498389_161795.

STAGE 4: efforts

Efforts to mitigate these campaigns are ongoing as of February 2021. The most prominent efforts are those by Twitter through account takedowns and the release of data to researchers, as well as an investigation and reporting of ProPublica.

Beginning in August 2019, ProPublica wrote computer programs that used Twint, an open-source Twitter scraping API, to find and scrape millions of interactions by potential bots within the network. These accounts were then analyzed and classified using network analysis and machine learning. Through this process, ProPublica was able to identify more than 10,000 suspected inauthentic accounts due to their profile characteristics (e.g., account name, twitter handle, account age, profile picture, etc.) and their activity (e.g., timing, frequency and content of posts, hashtags used, retweeting and liking activity, etc.) Using this method, we were able to identify a subset of more than 2,000 accounts that formed a network of artificial amplification of the fake accounts (i.e. the central accounts). Based on these indicators as well as offline reporting, we attributed this network to Chinese government operations with high confidence. This critical press exposed the existence of the network and was published on March 26, 2020.1

In preparation for publication, ProPublica shared a number of account names with Twitter. Twitter declined to respond specifically to ProPublica’s findings, but in June 2020 the company released its own dataset of accounts linked to the campaign.2 Some of these accounts and posts overlapped with data that ProPublica had collected from August 2019 to March 2020.

In addition, Twitter has detected and removed some of the accounts within the network, but it is unclear whether these takedowns were done by automated systems designed to catch influence campaigns, or whether these networks were identified by internal investigators. All accounts from the network are now either deleted or suspended.

Twitter’s data release has led to continued research and analysis of the Chinese state-linked fake account networks. In conjunction with Twitter’s June 2020 release, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) and the Stanford Internet Observatory produced reports analyzing the messaging and tactics of Chinese state-linked accounts.3 ASPI has traced accounts in the network to other social media platforms, such as and . These cross-platform connections have also been explored in detail by the research firm Graphika.4

- 1 Kao and Shuang Li, “How China Built a Twitter Propaganda Machine Then Let It Loose on Coronavirus.”

- 2 Twitter Safety, “Disclosing Networks of State-Linked Information Operations We’ve Removed.”

- 3Dr. Jacob Wallis et al., “Retweeting through the Great Firewall” (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, June 12, 2020), https://www.aspi.org.au/report/retweeting-through-great-firewall; Carly Miller et al., “Sockpuppets Spin COVID Yarns: An Analysis of PRC-Attributed June 2020 Twitter Takedown” (Stanford Internet Observatory, June 17, 2020), https://stanford.app.box.com/v/sio-twitter-prc-june-2020.

- 4Ben Nimmo et al., “Return of the (Spamouflage) Dragon” (Graphika, April 2020), https://public-assets.graphika.com/reports/Graphika_Report_Spamouflage_Returns.pdf.

STAGE 5: Adjustments by campaign operators

At this time, it is unclear whether the operators have adapted their tactics, or whether they are continuing to operate. Evidence suggests that similar operations are continuing despite platform crackdown and identification by researchers. In addition, new networks have also appeared — many with similar characteristics as those described here. An investigation by Italian news outlet Formiche, for example, found covert propaganda networks bots pushed pro-China Covid, Italian-language hashtags in Italy.1 Research by the Digital Forensics Center found similar Twitter bots spreading pro-CCP Covid propaganda in Serbia.2 Recent reporting also indicates that similar state-linked campaigns continue to respond to current events, and appear to increasingly target non-Chinese Twitter users. The New York Times, for example, reported that likely fake accounts linked to the Chinese government were artificially amplifying statements made by Chinese diplomats.3 However, without further analysis, it’s difficult to ascertain whether there is any relation between these campaigns.

- 1Gabriele Carrer and Di Francesco Bechis, “How China Unleashed Twitter Bots to Spread COVID-19 Propaganda in Italy,” Formiche, March 31, 2020, https://formiche.net/2020/03/china-unleashed-twitter-bots-covid19-propaganda-italy/.

- 2“A Bot Network Arrived in Serbia along with Coronavirus,” Digital Forensic Center, April 13, 2020, https://dfcme.me/en/dfc-finds-out-a-botnet-arrived-in-serbia-along-with-coronavirus/.

- 3Raymond Zhong et al., “Behind China’s Twitter Campaign, a Murky Supporting Chorus,” The New York Times, June 8, 2020, sec. Technology, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/08/technology/china-twitter-disinformation.html.

Cite this case study

Jeff Kao, "Astroturfing: How Hijacked Accounts and Dark Public Relations Faked Support for China's Response to COVID-19," The Media Manipulation Case Book, August 2, 2022, https://casebook-static.pages.dev/case-studies/astroturfing-how-hijacked-accounts-and-dark-public-relations-faked-support-chinas.