Butterfly Attack: Operation Blaxit

Overview

Over the course of 3 years, a mix of pranksters and extremists (right wing) launched a butterfly attack campaign as part of a meme war within an organic Black Twitter hashtag, and utilized digital blackface to amplify memes workshopped on 4chan. Overall, the campaign targeted Black activists and communities online in an effort to sow confusion, discredit authentic support, and suppress voter turnout for the Democratic Party. This campaign was redeployed several times to correspond to cultural trends or breaking news events.

STAGE 1: Manipulation Campaign Planning and Origins

The first organic use of #Blaxit (Black people’s exit) as a hashtag and viral slogan dates to June 2016, a play on the Brexit referendum that passed in the UK that same month. The initial uses of Blaxit were a mix of pro- and anti-Black sentiment from a variety of Twitter users. The phrase formalized on July 11, 2016, when physician and public health advocate Ulyssess Burley III published a tongue-in-cheek op-ed on the The Salt Collective entitled “#BLAXIT : 21 things we’re taking with us if we leave.”1 The op-ed explored implications of a Trump presidency on Black America, and suggested expatriation as a response. On its Twitter account, The Salt Collective indicated the article’s popularity crashed its website.2

The op-ed picked up traction when it was shared by social media influencer Awesomely Luuvie, who followed up with her own version of things black people would be taking with them upon exiting.3 NPR covered this emergent phenomenon in an interview with Burley on July 16, entitled “Disheartened By Racial Violence In U.S., Inspired By Brexit, He Pondered A 'Blaxit.”'4 On July 18, The Root also published an article about #Blaxit and black expats living abroad.5

The organic #Blaxit hashtag picked up traction in Black spaces online, and was the inspiration for a multi-wave by campaign participants organized on ’s “Politically Incorrect” board (/pol/).

The first post on /pol/ mentioning “Blaxit” was on June 6, 2016, in response to a video about a Black Brexiteer in the UK.6 It was used again in threads dedicated to anti-Black racism for the next several weeks, specifically in a July 10 thread responding to a Breitbart article about black nationalism and autonomy.7 Within this thread, campaign participants called for others to “Get this trending on Twitter,” 8 and the following day, another participant declared that “Operation #Blaxit is a go.” 9 In the first campaign threads on July 9 and July 11, campaign operators described the butterfly attack strategy: “We pretend to be blacks and tell blacks on social media to return to Africa since its not safe for blacks in America anymore.”10

Campaign participants on /pol/ noticed the articles and posts from The Salt Collective, Luuvie and NPR, and discussed how they may take advantage of this opportunity by hijacking the movement and altering the legitimacy of Black ex-patriot movements.11 Campaign operators created an “Operation Blaxit” thread, and continued to iterate ideas for the campaign over the next several days in various threads devoted to anti-Blackness and repatriation.12 The stated goals of the operation were not consistent for every participant, though the use of fake accounts impersonating Black social media users was suggested. Campaign operators suggested that this inauthentic behavior could be used as a wedge issue to discourage the Black vote for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election.13

The initial operation seems to have lost interest from 4chan users in July. However, it was rekindled on November 10, 2016, two days after the 2016 election. Campaign operators, noticing the trending of #Blaxit as a Black response to President Trump’s victory in the election, resuscitated the operation. There were five dedicated threads for a Blaxit butterfly attack that day.14 In these threads rife with anti-Black racism, participants workshopped crude designed to be inserted into the hashtag conversation on Twitter.15 In order to appear authentic, participants discussed mimicking popular aesthetics of Black protest and nationalist movements. “I feel like a lot of really positive fake Blaxit memes could easily trick ***** into thinking they are capable of 'self-determination'. Could work.” 16 wrote one user a Blaxit thread, using a racial slur we won’t reproduce here.

One anonymous campaign participant created a fake YouTube video (now deleted) and a series of memes, using the Black Lives Matter logo and designing a consistent Black and Yellow color scheme, sharing them in threads related to impersonating Black people seeking African expatriation.17 Some participants described the Blaxit campaign as a “psyop” later in December, continuing to share the black and yellow branded imposter memes.18 Scattered calls to get #Blaxit trending continued during the winter into spring 2017, though it was largely abandoned by participants for its lack of impact.

During early 2017, /pol/ attempted several similar campaigns designed to exploit prejudice and social wedges, including #NoTaxForBlacks.19 Participants in these threads discussed creating and maintaining inauthentic accounts to impersonate Black people on Twitter, and attempts to seed into Black online spaces.

On June 26, 2017, the Operation Blaxit campaign became more organized. The creators of the operation left detailed instructions for potential participants on 4chan, and an agenda hosted on Pastebin.20 Participants workshopped memes, created false accounts, set up , and gathered supporting data to create the impression of an emergent movement of African repatriation by a group of Black Americans. The campaign’s style guide included specific instructions, such as:

“Make a fake twitter account and retweet the shit out of the memes in the drive, or just post material relevant to Blaxit. Tweet about other things too and follow relevant individuals (@officialblaxit, rappers, antifa, feminists, etc.) to make the account look legitimate. Alternatively, make , websites, channels, or any other sort of media that can contribute to the movement.”21

The anti-Black campaign participants expressed unfamiliarity with Black cultural expression, so campaign organizers included several articles and a wikipedia page that contained a list of Black scientists, inventors, and scholars to draw from for inspiration in creation of artificial pro-Black tweets. Stylistically, they focused on sources of Black pride and power. Their strategy included launching crowdfunding efforts to generate revenue for ad space and more polished video content, real websites, and an official “manifesto.” 22

Learning from earlier Blaxit and the #NoTaxForBlacks efforts, this time campaign operators applied a high level of specificity to the content in order to more legitimately mimic Black people and the Black Lives Matter movement explicitly. Memes were designed using the black and yellow esthetic and the branding of BLM, down the stripe. They used consistent fonts — American Typewriter, Kingthings Typewriter, and Gabriella Ribbon FG. Though not all of the graphics were in black and white, they encouraged people to use black and white stock photos and to focus on images that have a civil rights theme or conjure up the “Black American Dream.”23

- 1“‘#BLAXIT : 21 Things We’re Taking with Us If We Leave,’ by Ulysses Burley III,” The Salt Collective, July 11, 2016, https://thesaltcollective.org/6936-2/.

- 2The Salt Collective (@salt-collective), ”You beautiful people crashed our site all trying to read #BLAXIT at once! @ulyssesburley https://shar.es/1lyfRr,” Twitter, July 11, 2016, https://twitter.com/salt_collective/status/752608522714525696.

- 3“#BLAXIT: More Things We’re Taking With Us If We Leave,” Awesomely Luvvie (blog), July 11, 2016, https://www.awesomelyluvvie.com/2016/07/blaxit-taking-with-us.html.

- 4“Disheartened By Racial Violence In U.S., Inspired By Brexit, He Pondered A ‘Blaxit,’” NPR.org, July 17, 2016, https://www.npr.org/2016/07/17/486359426/disheartened-by-racial-violence-in-u-s-inspired-by-brexit-he-pondered-a-blaxit.

- 5Dayvee Sutton, “Want to Pull a #Blaxit? Becoming a Black Expat Is Harder Than You Think,” The Root, July 18, 2016, https://www.theroot.com/want-to-pull-a-blaxit-becoming-a-black-expat-is-harde-1790856053.

- 6Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #76302233,” 4chan, June 6, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/76302233/#76303190.

- 7Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #80529833,” 4chan, July 10, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/80529833/#80529833.

- 8Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #80529833.”

- 9Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #80604818,” 4chan, July 11, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/80604818/#80608946.

- 10Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #80651815,” July 11, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/80651815.

- 11Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #80894140, July 13, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/80894140.

- 12Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #81968239,” 4chan, July 20, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/81968239/#81971329.

- 13Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #81968239.”

- 14Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #97699291,” 4chan, Nov 10, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/97699291/#97699291; Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #97704260,” 4chan, Nov 10, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/97704260/#97704260; Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #97704260,” 4chan, Nov 10, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/97707136/#97707136; Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #97716211,” 4chan, Nov 10, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/97716211/#97716211; Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #97747770,” 4chan, Nov 10, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/97747770/#97747770.

- 15Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #97716211,” 4chan, November 10, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/97716211/#97716211.

- 16Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #80894140,” 4chan, July 13, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/80894140/#80897839.

- 17This video is no longer available, but it was hosted at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pBWN6sJTAOE; Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #99766481,” 4chan, November 22, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/99766481/#99773774.

- 18Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #102619794,” 4chan, December 12, 2016, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/102619794/#102619794.

- 19Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #127488808,” 4chan, May 28, 2017, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/127488808/#127488808; Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #127519664,” 4chan, May 28, 2017, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/127519664/#127519664.

- 20A Guest, “Untitled,” Pastebin, June 26, 2017, https://pastebin.com/EDiW5jQQ.

- 21A Guest, “Untitled.”

- 22A Guest.

- 23Ibid.

Stage 2: Seeding Social Media

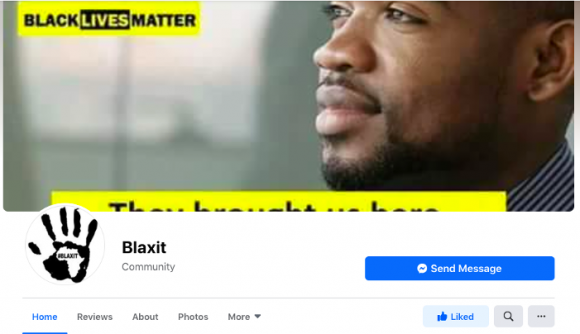

In lieu of creating a separate hashtag, users instead sought to astroturf the pre-existing #Blaxit hashtag. They made an “Official Blaxit” logo, website,1 Instagram,2 Facebook page,3 and Twitter profile4 to maximize search results and mimic the online presence of a social movement. They seeded their materials through the #BlackLivesMatter and #BLM hashtags.5 In response to the initial stage-setting of campaign organizers, other participants in the campaign set up Blaxit-branded accounts across all major platforms, including Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr6 , YouTube7 and Facebook. Calls to participate were posted in other far-right communities, like ’s the_donald.8 These accounts used images of pro-Black memes or images of Black people taken from the and social media as avatars. The YouTube channel “Cultural Refugee,” which was part of the campaign, featured video content of several Black men, including retired NFL player Cris Carter, and routed people to a now defunct website officialblaxit.org, run by the campaign operators.9

- 1Official Blaxit, July 1, 2017, accessed via web.archive.org, https://web.archive.org/web/20170701113714/http://officialblaxit.org/.

- 2Blaxit (@officialblaxit), , https://www.instagram.com/officialblaxit/.

- 3Blaxit, , https://www.facebook.com/Blaxit-698683190342056.

- 4Blaxit (@BlaxitOfficial), Twitter, https://twitter.com/blaxitofficial.

- 5Adam (@HobbitHarry81), “Support the undoing of racism and bigotry. Celebrate Diversity #Blaxit #BLM #BlackLivesMatter #Diversityisstrength,” Twitter, June 27, 2017, https://twitter.com/HobbitHarry81/status/879834257132322817.

- 6blaxxodus, “Black Exodus,” tumblr, https://blaxxodus.tumblr.com/.

- 7Cultural Refugee, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeCFQtnETjeUVWlmx0-rI0w.

- 8This page has been banned from reddit, but it was hosted at: https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Donald/comments/5c8vvh/blaxit_seems_to_be_a_thing_now_black_people/.

- 9Cultural Refugee.

Campaign participants shared and celebrated when people interacted with their content. “This is like catfishing an entire race,” wrote a participant on /pol/.1 Their multi-platform amplification strategy included following, tagging, and tweeting at Black news outlets and celebrities in the hopes they would retweet the content.2 Some participants shared the content with their alt-right accounts, an action that was criticized by campaign participants.3

- 1Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #131399612,” 4chan, June 26, 2017, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/131399612/#q131407173.

- 2Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #131399612,” 4chan, June 26, 2017, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/131399612/#q131424833.

- 3Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #131399612,” 4chan, June 26, 2017, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/131399612/#131416016.

Stage 3: Responses by industry, activists, politicians, and journalists

On the whole, the content of the Blaxit butterfly attack does not appear to have been discussed by groups, platforms, or policy-makers. Several social media users did identify the campaign as being manipulated by participants from /pol/. Attempts to tweet at high-profile accounts did not seem to get a lot of positive pickup. In one notable example, Black Lives Matter DC’s Twitter account, @DMVBlackLives, quickly shut down attempts to get it to retweet the fake Blaxit content. @DMVBlackLives recognized it was being targeted and accurately assessed the campaign participants as trolls and .1 To the campaign operators, though, even this negative attention was considered a chance to engage further.2 Others suggested that any attention, even or suspicion, was a sign of success.3 Some campaign participants misidentified The Root’s #Blaxit travel series as evidence of their influence,4 though there is no evidence this series is connected to the inauthentic behavior.5

Stage 4:

Many of the accounts and websites associated with the first wave of Operation Blaxit have since been removed. It is unclear if these accounts were removed by users, deleted directly by the platform, or because they were flagged for abuse. Some on social media who discovered the sought to mitigate the campaign through community-led debunking. They took to 4chan to spam the words “fake” and “hoax” with Blaxit, so as to redirect internet search engines to help diffuse the impact of the campaign.6 On Reddit, some users pointed out the campaign came from 4chan and warned their followers on Twitter.7 Campaign participants discussed their failures on 4chan. In the thread where they were discussing DC BLM, users proposed organizing offsite and publically blaming Reddit for ruining the campaign. They considered feigning a movement of “real Black activists” that would accuse the unveiled trolls of hijacking the movement. Meanwhile, they continued to foster division and spread the core Blaxit memes.

Continued organic use of #Blaxit by Black press and social media users has helped mitigate the impact of the manipulation campaign. This conversation was driven by Black social media users in response to BLM protests, and reduced the saturation and visibility of the 4chan posters in searches through the hashtag. The hashtag has been used alongside, or as a misspelling of, Blexit, a conservative brand operated by Candace Owens and Brandon Tatum.

Stage 5: Adjustments by manipulators to new environment

- 1Black Lives Matter DC (@DMVBlackLives), “Yes, #Blaxit is a troll campaign for sure. 😂😂😂 We were entertained nonetheless,” Twitter, June 27, 2017, https://twitter.com/DMVBlackLives/status/879776190365659137.

- 2Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #131535054,” 4chan, June 27, 2017, accessed via 4plebs, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/131535054/#131544579.

- 3Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #131452340,” 4chan, June 26, 2017, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/131452340/#131454525.

- 4Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #131379430,” 4chan, June 26, 2017, accessed via 4plebs, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/131379430/#131383078.

- 5Dayvee Sutton, “Want to Pull a #Blaxit? Becoming a Black Expat Is Harder Than You Think.”

- 6Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #131687029,” 4chan, June 28, 2017, accessed via 4plebs, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/131687029/#131703598.

- 7u/BlasianTyga, “Be Wary Of ‘Black’ People Promoting A #Blaxit Or ‘Back To Africa Movement’ On Social Media, The Alt-Right Has Launched A ‘Meme Operation’ To Convince Black-Americans To Self-Deport,” reddit, July 8, 2017, https://www.reddit.com/r/JustProBlackThings/comments/6m2ca7/be_wary_of_black_people_promoting_a_blaxit_or/.

From June 2016 to October 2020, there were 1,799 posts mentioning “Blaxit” on /pol/,1 and 113 unique threads that contained “Blaxit” in the subject.2

While this long-running campaign has seen little success in influencing conversation among Black social media users or other perceptions of impact, campaign participants have redeployed it repeatedly over the years. This includes: a prevalent use of the hashtag in the UK as a direct foil to Brexit; conflation with the right wing hashtag #blexit;3 the use of the hashtag in connection to Black Lives Matter protests in 2020; and the use of hashtag in connection to the “The Year of the Return,” a initiative of the Government of Ghana intended to drive diasporan interest, investment and tourism.4 It was also deployed in the lead up to the release of Black Panther in 2018,5 and in a few instances in 2019.

Among the far right, Blaxit has become a code word for anti-Black racism, and a strawman used for right-wing videos. In April 2019, a Daily Stormer blog post about the Duke and Duchess of Sussex’s visit to Africa, shared many of the Blaxit memes, showing the diffusion of the memes in far right networks.6

In June 2020, a new deployment of the butterfly attack circulated on social media in the form of a video called “MFW Blaxit.”7 The meme video combined previous examples of real back-to-Africa articles with faked Blaxit images, clearly mined from 4chan posts. The video was also shared on YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram.8

Blaxit memes have also been used in content by some conservative and right-wing YouTubers. In “Rebuttal: “Blaxit,”9 Right wing YouTuber Steven Crowder uses a superficial reading of the real Blaxit movement to attack BLM and Pan-African solidarity. The video uses a meme of the /pol/ Blaxit campaign in the video’s thumbnail, indicating that someone involved with the video process sourced the image for the title card, yet concealed any mention of the 4chan campaign in the actual video content. YouTuber Mr Obvious summarizes 4chan posts and culture war news stories in short videos, including IOTBW10 and other campaigns organized on 4chan and /pol/. On Jun 26, 2020 he released a video entitled “BLAXIT, African Americans Are LEAVING the USA, #Blaxit Makes a Comeback.”11 He describes the original movement as organic, but directs viewers to specific inauthentic organizing threads in screenshots.

But by far the most significant redeployment has been during the Black Lives Matters protests over the summer of summer 2020.12 The hashtag became more popular organically at this time, offering a new opportunity to reactivate the campaign. Amid the very real social movement, several inauthentic accounts or explicitly right-wing accounts shared the hashtag and the original Blaxit memes. None seem to be impacting conversations outside the far right.13

- 1Comment search results ”Blaxit,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, Oct 16, 2020, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/search/text/blaxit/.

- 2Subject search results “Blaxit,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, Oct 15, 2020, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/search/subject/blaxit/.

- 3Nadine White, “Why Black Brits Are Considering Leaving UK After Election: 'If The Conservatives Win, I'm Gone,'” HuffPost, November 12, 2019, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/boris-johnson-track-record-on-race_uk_5de7dfece4b0913e6f895667.

- 4Kim Hjelmgaard, “Black Americans leave USA to escape racism, build lives abroad,” USA Today, June 26, 2020, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2020/06/26/blaxit-black-americans-leave-us-escape-racism-build-lives-abroad/3234129001/.

- 5Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #157401620,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, January 20, 2018, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/157401620/#157417846.

- 6Andrew Anglin, “Thankfully, Prince Harry Is Taking His ****** Wife and ****** Child and Moving to Africa,” Daily Stormer, April 21, 2019, accessed via archive.is, https://archive.is/06oMG.

- 7This page has been banned from reddit, but it was hosted at: https://www.reddit.com/r/imgoingtohellforthis2/comments/hdp633/mfw_blaxit/.

- 8This link has been removed, but it was hosted at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CBlZ5UnAlRK/.

- 9Steven Crowder, “REBUTTAL: Blacks Need to Leave!?,” YouTube, 17:31, April 9, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6oHhA747SGU.

- 10Mr. Obvious, “4chan's Spooky Halloween: IOTBW Rises Again,” YouTube, 9:27, October 23, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ervEYvZ7ZSA.

- 11Mr. Obvious, “BLAXIT, African Americans Are LEAVING the USA, #Blaxit Makes a Comeback,” YouTube, 12:34, June 26, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nMD_B8ShaJs.

- 12Anonymous, “/pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #260452673,” 4chan, June 2, 2020, accessed via 4plebs, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/260452673/#260452673.

- 13Write Winger (@RealWriteWinger), “Even if all BLM’s demands are met and reparations are paid, in a country of 197 million white people, black people will still be living as a minority under systemic racism and white supremacy. There’s only one solution: #BLAXIT,” Twitter, June 26, 2020, https://twitter.com/RealWriteWinger/status/1276714079189561345; Politrickers = Politicians Conning Its People (@Politrickers), “Hey “Africans In America” or so-called “African-Americans,” there are places in the world where you will not be known or called a “black woman” or “black man.” You will simply be identified as a “woman” or “man.” LET’S GO. #Blaxit,” Twitter, June 26, 2020, https://twitter.com/Politrickers/status/1276543722839248898.

Cite this case study

Brandi Collins-Dexter, "Butterfly Attack: Operation Blaxit ," The Media Manipulation Case Book, July 8, 2021, https://casebook-static.pages.dev/case-studies/butterfly-attack-operation-blaxit.