TikTok, the War on Ukraine, and 10 Features That Make the App Vulnerable to Misinformation

As Vladimir Putin continues to wage war in Ukraine, the video sharing app is an increasingly popular source of digital content about the invasion. Videos on the feature on-the-ground updates, testimonials from within Ukraine, and calls to action (such as requests for donations and political advocacy). Some of these are authentic, and some are hoaxes. How can we tell the difference?

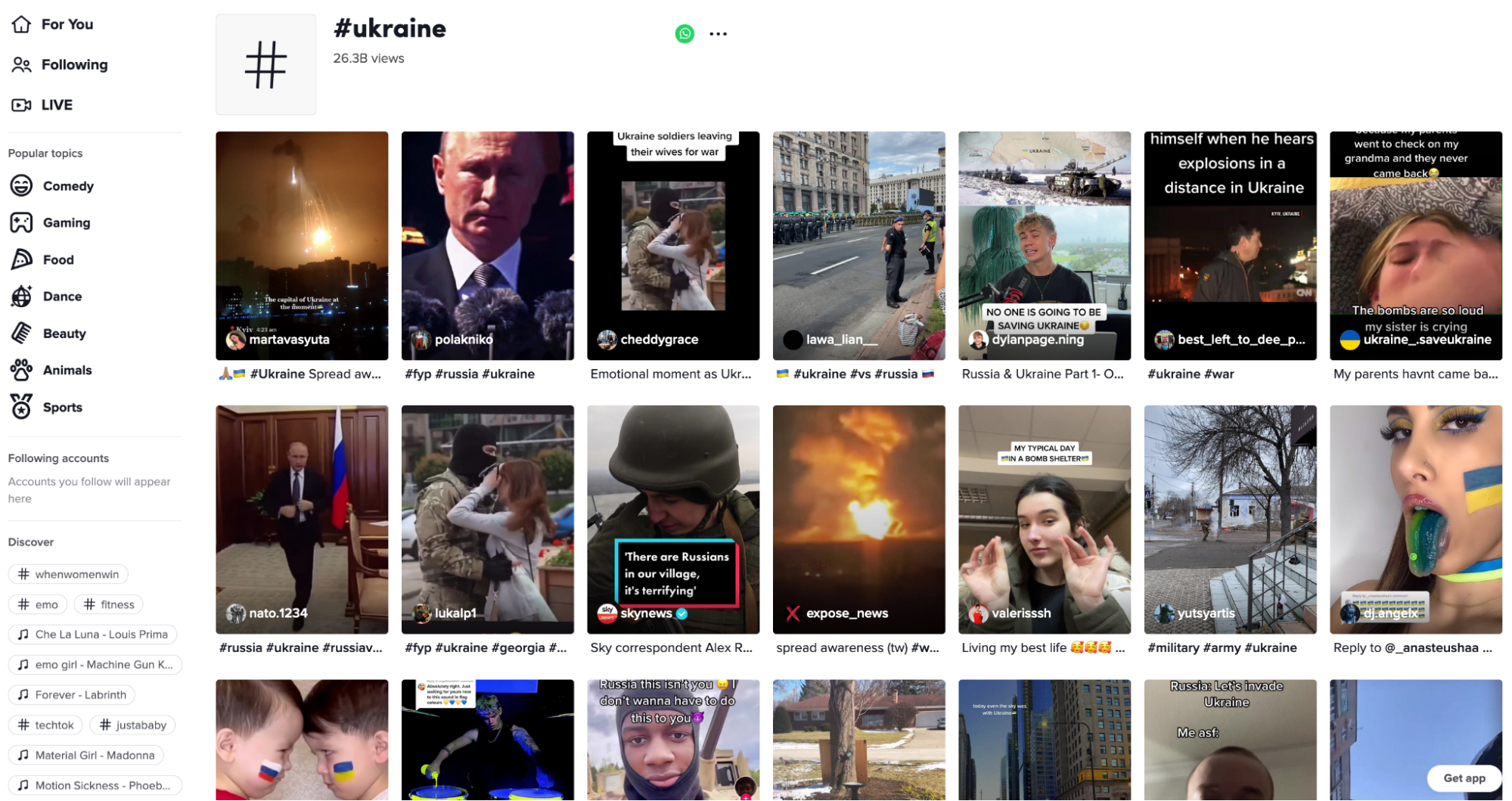

At the time of writing on March 9, 2022, videos on TikTok featuring the hashtag “#ukraine” had collectively amassed more than 26.8 billion views. In comparison, the hashtag “#ukraine” on had 33 million posts (hovering over the below image and others in the text will display image source).

Since Feb. 24, 2022, the Technology and Social Change team at Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center has been monitoring and cataloging the discourse about Ukraine across the major social media platforms in the U.S. In this popularity contest, where the race to publish challenges the commitment to truth, it’s incumbent upon those who create information systems to ensure they are not abused and to protect vulnerable groups from attack. Over the last few years, we have witnessed the enormous financial success of social media companies, who have managed to scale their systems to reach hundreds of millions of people instantaneously. Along with that success has followed the rapid scaling of and campaigns, which capitalize on the design of social platforms to reach massive audiences extremely quickly.

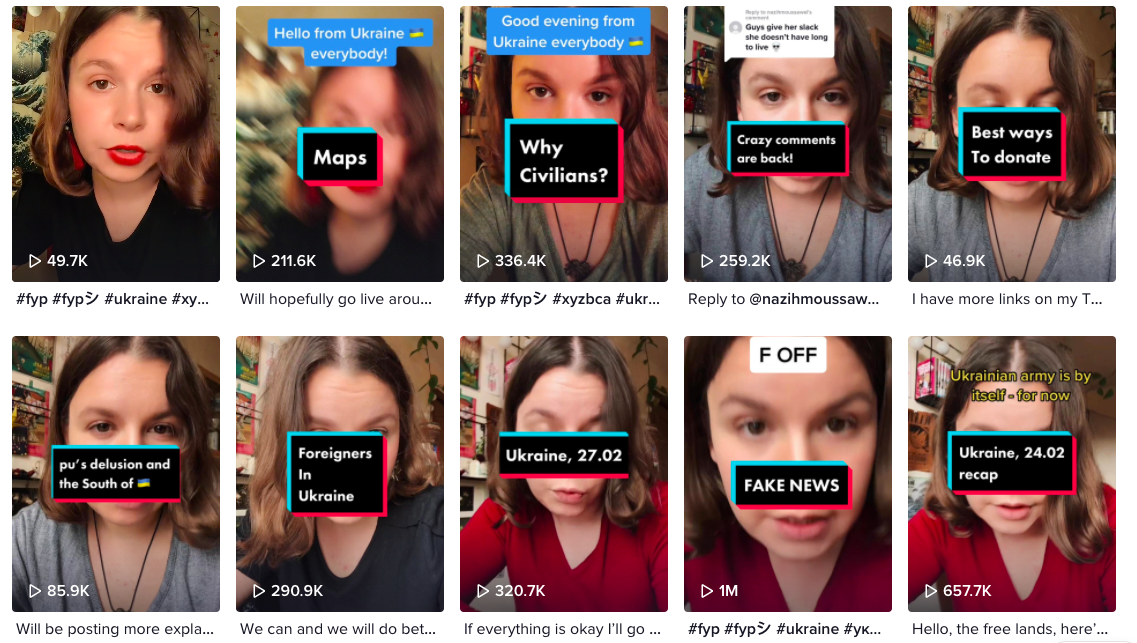

It’s not all bad, though. We have observed TikTok users inside Ukraine using the app to raise awareness about the crisis and document their experiences under siege. These videos range from sardonic to deeply emotional. Videos detailing the violence and destruction occurring in several of the country’s major cities are also common on the app. Ukrainians in and outside the country are using the platform to speak directly to western audiences who may not know the history of Ukraine. A good example of this can be seen on the account @xenasolo, run by a woman who identifies as Crimean who has been contextualizing the situation in Ukraine for English speaking audiences since before the February invasion.

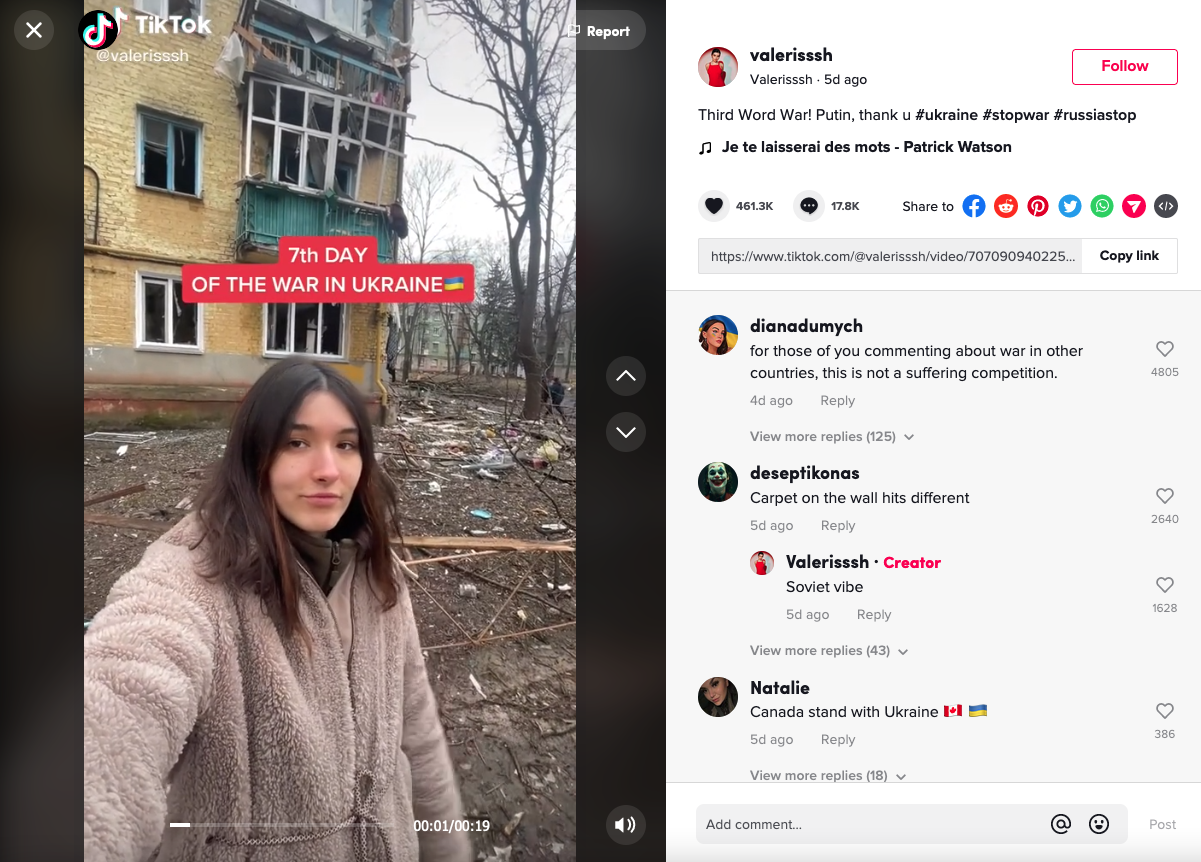

Other accounts, such as @valerisssh and @moneykristina, frequently post videos that debunk internet rumors and share glimpses into the horrors Ukrainians are experiencing as the invasion continues. They show scenes of Putin’s destruction of the country, such as collapsed and mangled buildings, daily life from inside bomb shelters, empty grocery shelves and long lines for gas.

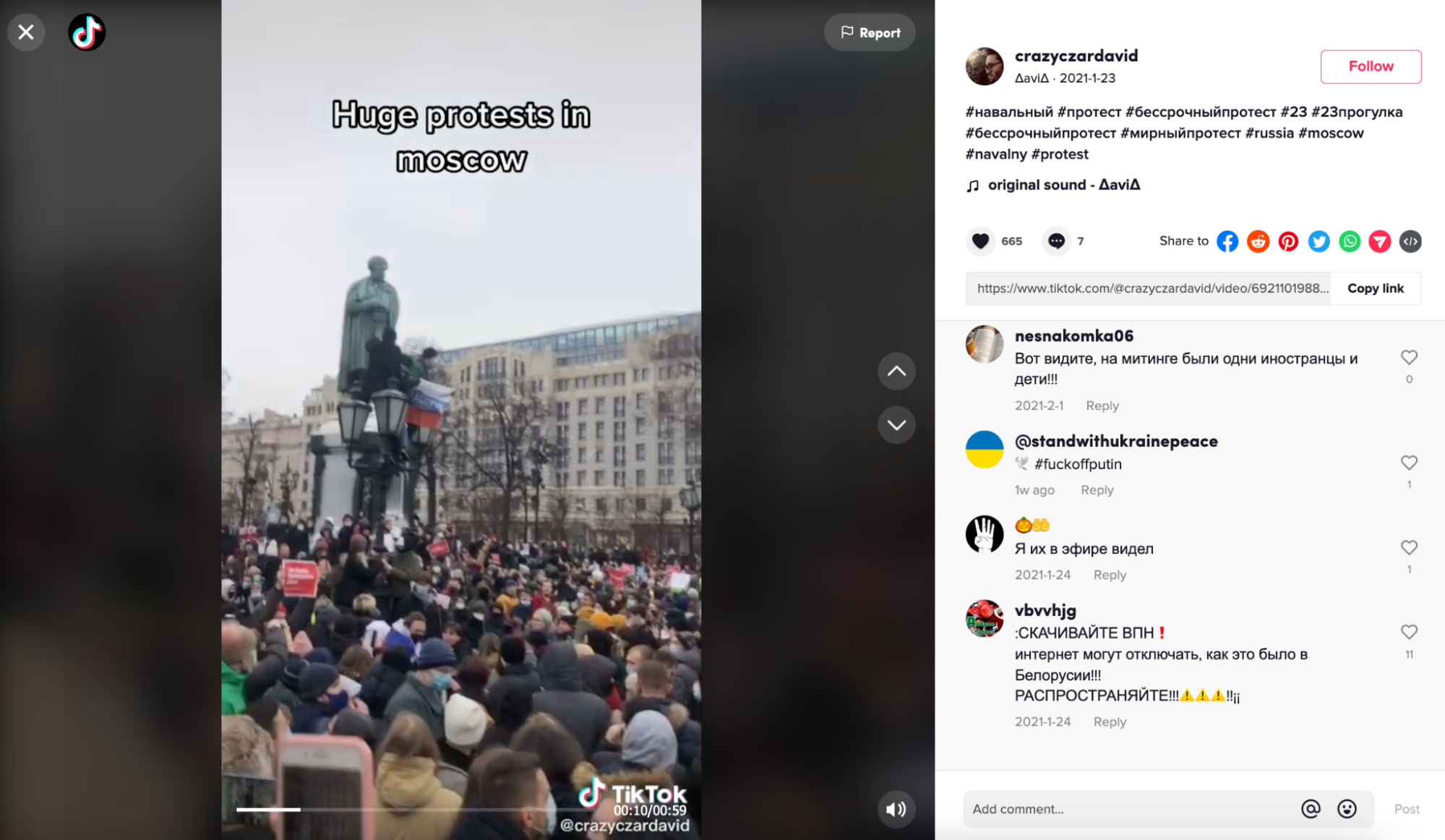

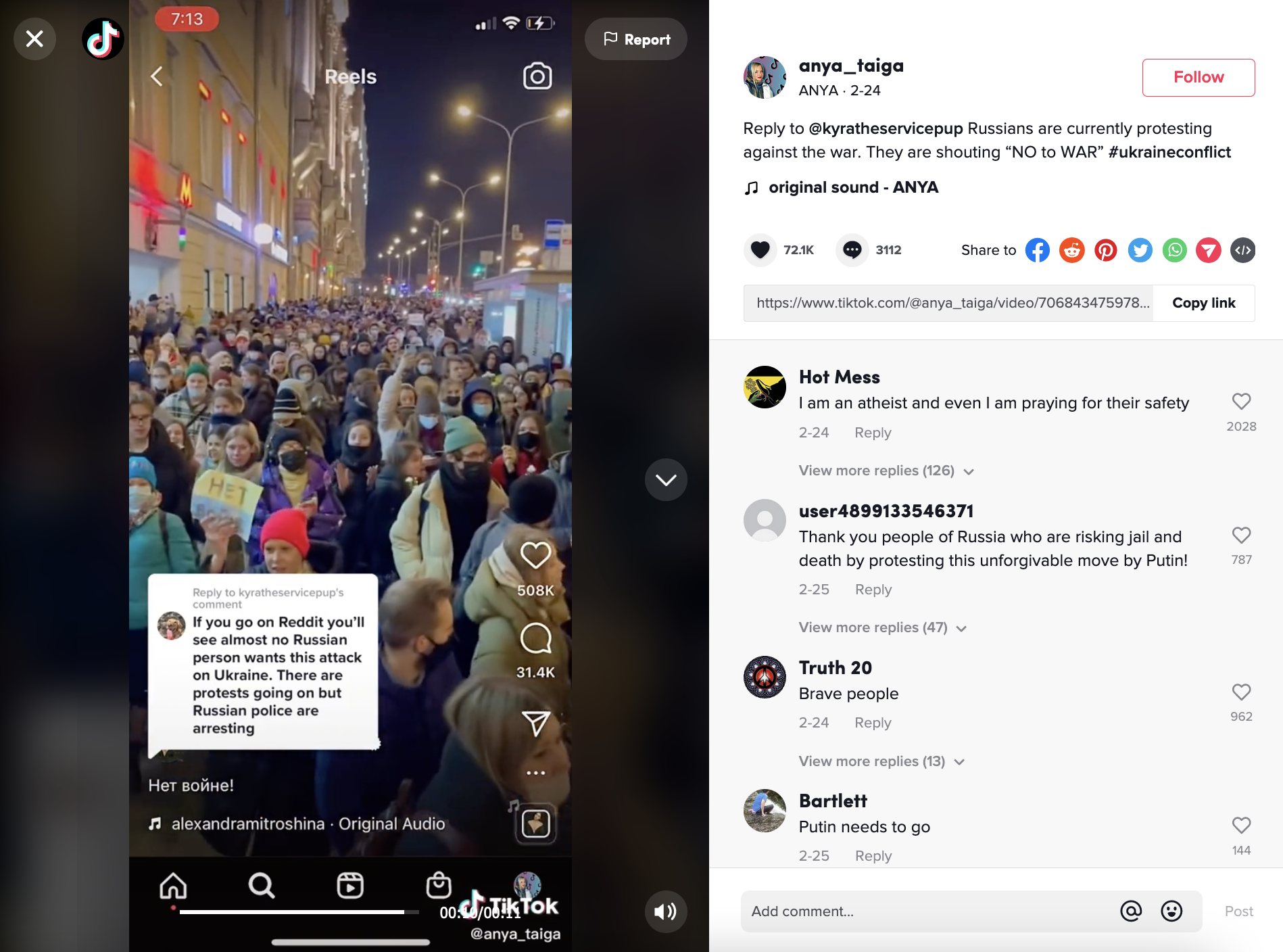

Russian users, on the other hand, have been barred from uploading and livestreaming to the platform since March 6, 2022, when TikTok suspended service in the country in response to a Russian law criminalizing “fake news” (meaning information that conflicts with state-sanctioned reports related to the invasion).1 Before that, many Russian users posted videos of the antiwar protests that broke out at the onset of the invasion in Moscow and other Russian cities.

- 1Sheera Frenkel, “TikTok Suspends Livestreaming and New Uploads from Russia,” The New York Times, March 6, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/06/technology/tiktok-russia-ukraine.html.

Despite TikTok’s suspension of service in Russia, many Russian-owned and even state-run TikTok accounts are still visible on the platform, and videos posted from inside Russia prior to March 6 can still be viewed and commented on.1 As such, these suspended accounts could still kindle or reignite pro-Russian sentiment if they were to be amplified by the app’s For You algorithm or reposted by other users.

TikTok’s decision to suspend its services in Russia has also failed to prevent pro-Russian accounts from cropping up outside of Russia. In the US, TikTokers are taking to the platform to express their support for Putin and for the Russian army by posting clips of Putin’s old speeches, favorable news clips, and pro-Russian memes.

Despite debunks, these videos continue to go viral on TikTok, raking in millions of views. This results in a “muddying of the waters,” meaning it creates a digital atmosphere in which it is difficult – even for seasoned journalists and researchers – to discern truth from rumor, parody, and fabrication. In effect, without robust metadata, it’s difficult to know much about the origins of a video or how it is being amplified on the platform.

The Design of TikTok Makes Certain Media Manipulation Easy

We have observed instances of mis- and disinformation across all the major social media platforms during the in Ukraine. Shared social media features, such as the use of anonymity in usernames and the ease with which content can be reposted, can make it hard to trace a post to its source across many platforms. This sourcing becomes even more challenging during breaking news events, when the demand for on-the-ground updates outpaces the speed at which reliable, authoritative news sources can verify information. In this search for news, people turn to social media platforms to fill the gaps.

TikTok, in particular, presents a unique challenge for viewers attempting to decipher fact from fiction, according to our research. Several features of TikTok's technological infrastructure and user culture make the platform particularly susceptible to hosting and spreading and other forms of viral misinformation.

1. On Tiktok, anyone can publish and republish any video, and stolen or reposted clips are displayed alongside original content.

TikTok’s intellectual property policy does “not allow posting, sharing, or sending any content that violates or infringes someone else's copyrights, trademarks or other intellectual property rights.”2 Even so, the algorithm doesn't punish users who post movie clips and the like. Professionally made content such as movies and music videos also are served in the same places as personal testimonials.

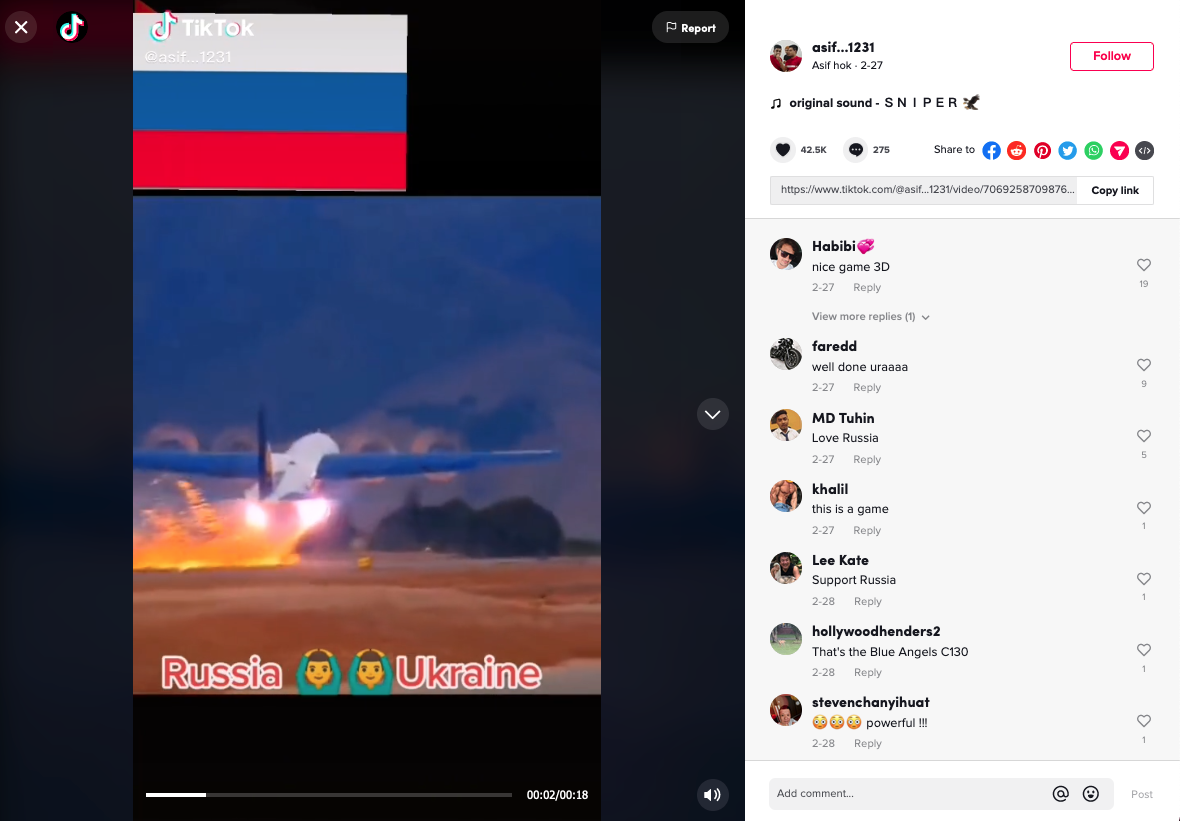

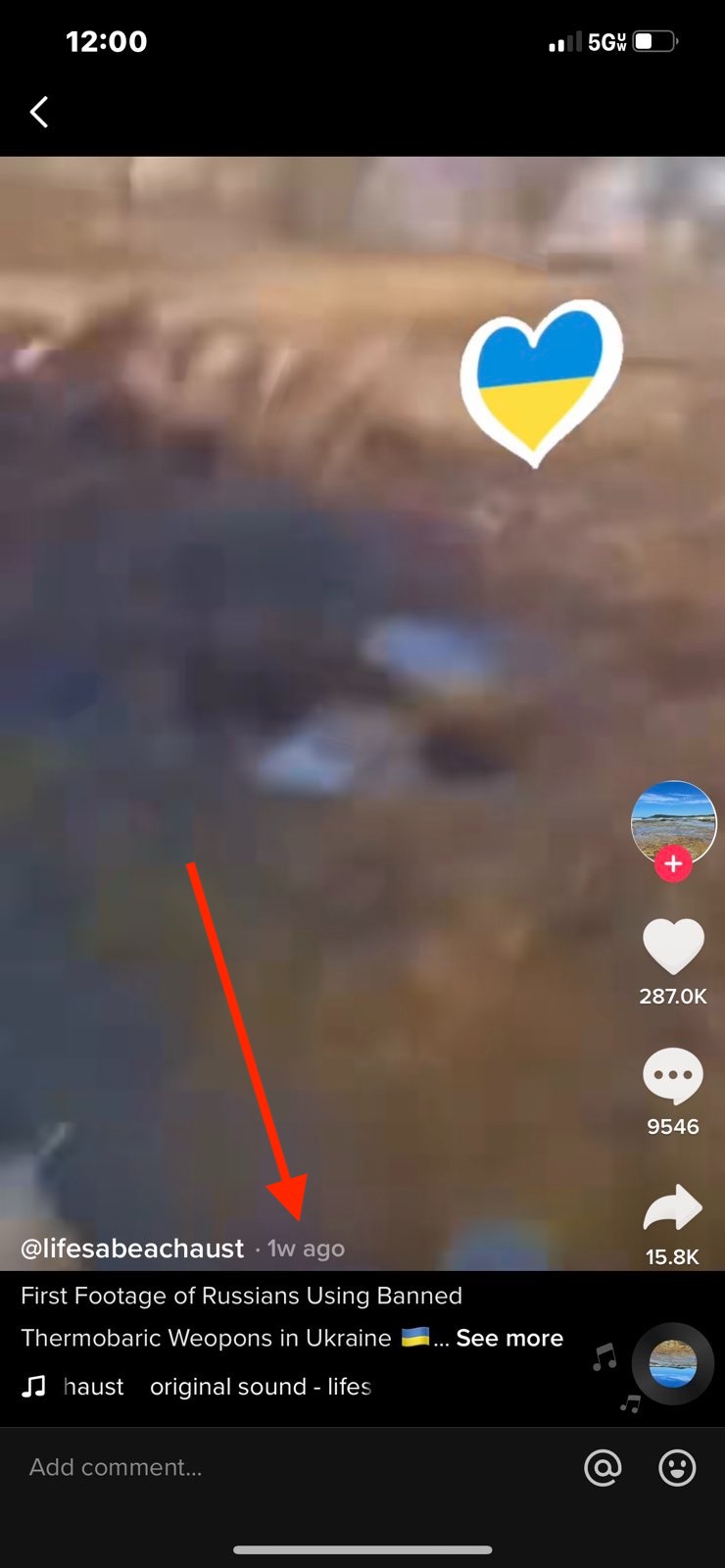

Here is an example of a video that has been taken from a video and reposted to TikTok without attribution, as if it were related to the invasion:

- 1 “RT NEWS (@rt.News),” TikTok, accessed March 9, 2022, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/CR29-8ZSC; “ТАСС (@tass_agency),” TikTok, accessed March 9, 2022, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/27S8-6WWT; “РИА Новости (@ria_novosti),” TikTok, accessed March 9, 2022, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/KK8N-A8Q3.

- 2 “How Does Tik Tok Use Music Legally?,” Tech Junkie, July 10, 2020, https://social.techjunkie.com/how-does-tik-tok-use-music-legally/; “Intellectual Property Policy,” TikTok, June 7, 2021, https://www.tiktok.com/legal/copyright-policy?lang=en.

Although the video, posted on Feb. 27, 2022, is captioned as if it depicts a recent scene from within the invasion, PolitiFact debunked it as being stolen from a 2017 YouTube video showing one of the Blue Angels, a U.S. Navy flight demonstration squadron.1

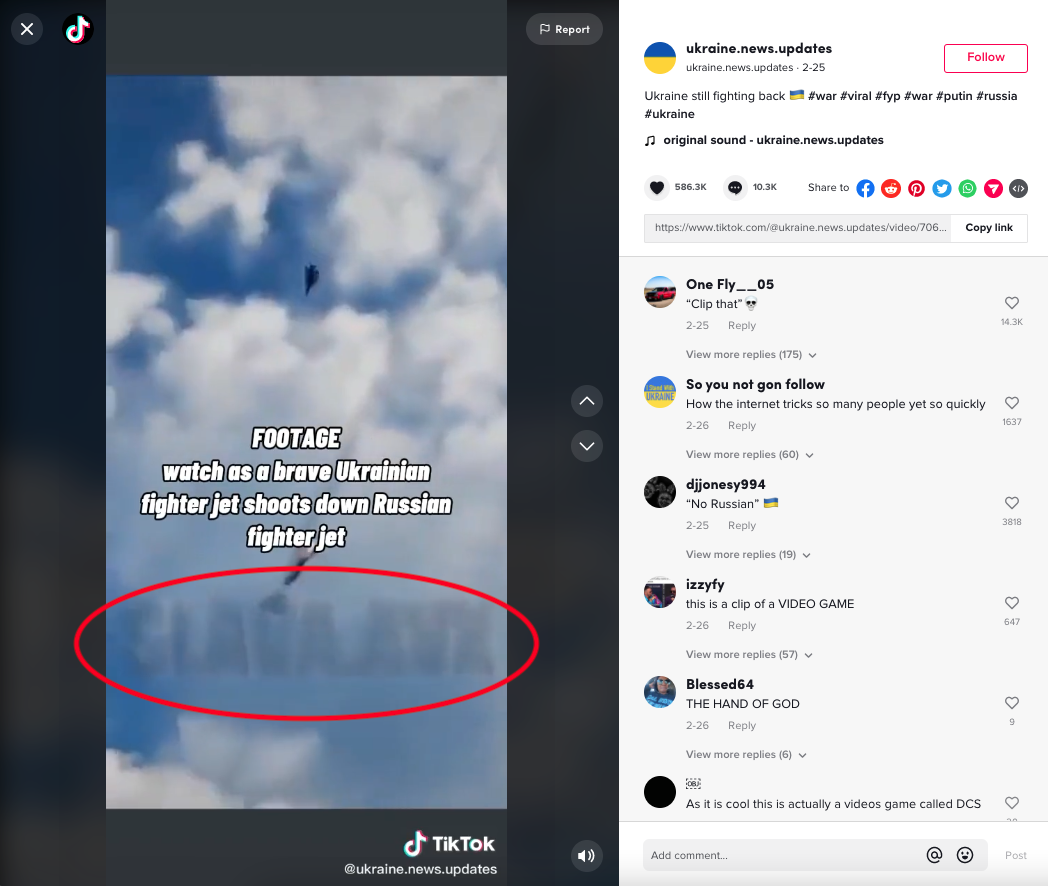

Another example (seen below) claiming to show a Ukrainian fighter jet shooting down a Russian plane has been debunked by Snopes and others as a clip from the video game, “Digital Combat Simulator.”2 In this case, the watermark on the video, which bears the username of someone other than the user posting it, gives it away as stolen footage.

- 1 Bill McCarthy, “As Russia Invades Ukraine, Misinformers Exploit TikTok’s Audio Features to Spread Fake War Footage,” PolitiFact, March 4, 2022, https://www.politifact.com/article/2022/mar/04/russia-invades-ukraine-m….

- 2 Dan Evon, “Is This ‘Ghost of Kyiv’ Video Real?,” Snopes, February 25, 2022, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/is-this-ghost-of-kyiv-video-real/.

2. Pseudonyms are popular on TikTok, making it harder to discern who a poster is, where they are, and whether their video content is original or real.

Many TikTok channels are pseudonymous, meaning the person posting to them does not publish their real name, and uses a screen name or handle instead. Anonymity (when a user posts with no personal details or way to trace the post to other online activity) and pseudonymity (the use of a name other than their real name to post or build an audience) are core to the internet – from chat rooms to social media platforms. In contrast, users on platforms like and tend to use their real names and to post autobiographical details about themselves. Oppositely, on , users are completely anonymous, and can only be identified by their unique tripcodes.

Examples of pseudonymity on TikTok can be seen throughout this research in usernames such as @stopthwar, @blue_eyes_1223, and @redsparrowpeaky, none of which reveal the true identifies of their owners.

This pseudonymity, within TikTok’s culture of quick reposting and easy-to-replicate audio, is a feature that contributes to the challenge of finding the source (or the component parts) of a video. Pseudonymous accounts lack biographical and geographical information, which is essential context for viewers attempting to determine if someone is posting their own video or reposting content that came from somewhere else.

3. Factual information about TikTok videos – especially the dates and times of publication – are not clearly displayed for viewers on TikTok mobile app.

Crucial metadata that can help verify images and videos – such as the date on which something was uploaded to the site – are not clearly displayed on TikTok’s mobile app. This information is accessible, but is much easier to find using the desktop version of TikTok. The main way users consume TikTok videos, however, is via the mobile app, which as of 2020 had been downloaded 315 million times. The challenges outlined below represent the mobile user’s experience trying to timestamp content on TikTok.

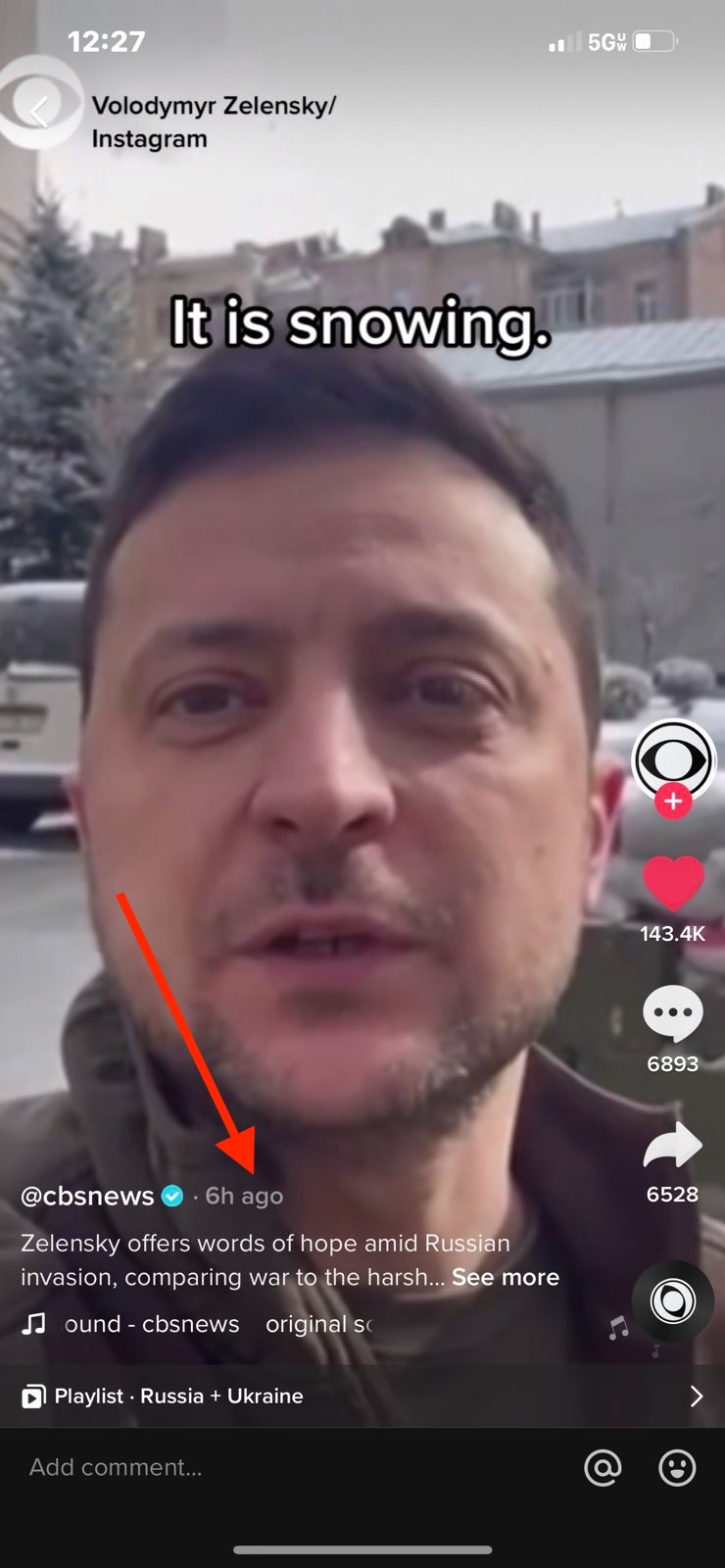

On other social media platforms, such as Twitter or Facebook, the date and time a post was created is a fixed piece of data that accompanies the post no matter how long it has been on the site and no matter how a user comes across it (be that on their news feed or through a retweet or search). But on TikTok this information is not displayed automatically when a video is presented in a user’s feed. When a user comes across a video on their personalized, somewhat randomized "For You Page," there is no date or time displayed. Users need to take multiple actions to figure out when it was posted. If a user “likes” that video and then looks back at it, the date appears in small text next to the name of the user who uploaded it. The date is also visible on a video if that video is found through search, rather than directly on a person’s For You Page.

Here is how a video is presented on the FYP, sans date:

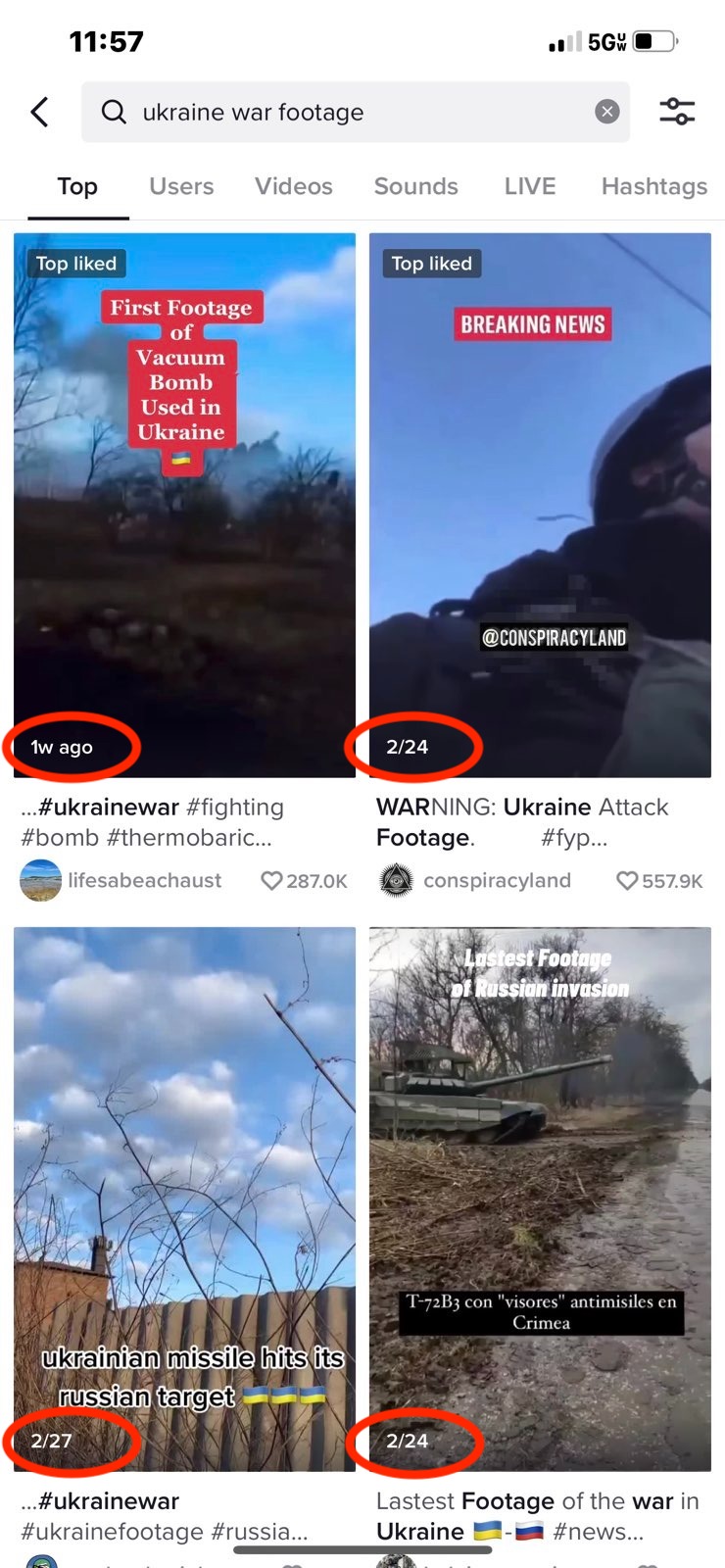

When searching for videos by specific users or about specific topics, the search grid of videos shows some date information, but the varies. If the video was uploaded within one week it may display “1w ago,” whereas videos uploaded longer ago than that will have a date. Viewers can’t tell what time of day a piece of content was uploaded, unless they are looking at the video the day it first hit the app, in which case the app will indicate how many hours old the video is. Here is an example of the kind of date information displayed when searching for videos about “ukraine war footage,” a phrase TikTok suggested after typing in “Ukr.”

Comments, on the other hand, are always accompanied by an automated date no matter whether one finds the video through search or the For You Page, so one way to assess the timeframe something was uploaded is to click on the comments and see when they were left. This is imprecise, however, as comments could have been left at any time after a video was uploaded, and there is no hourly information.

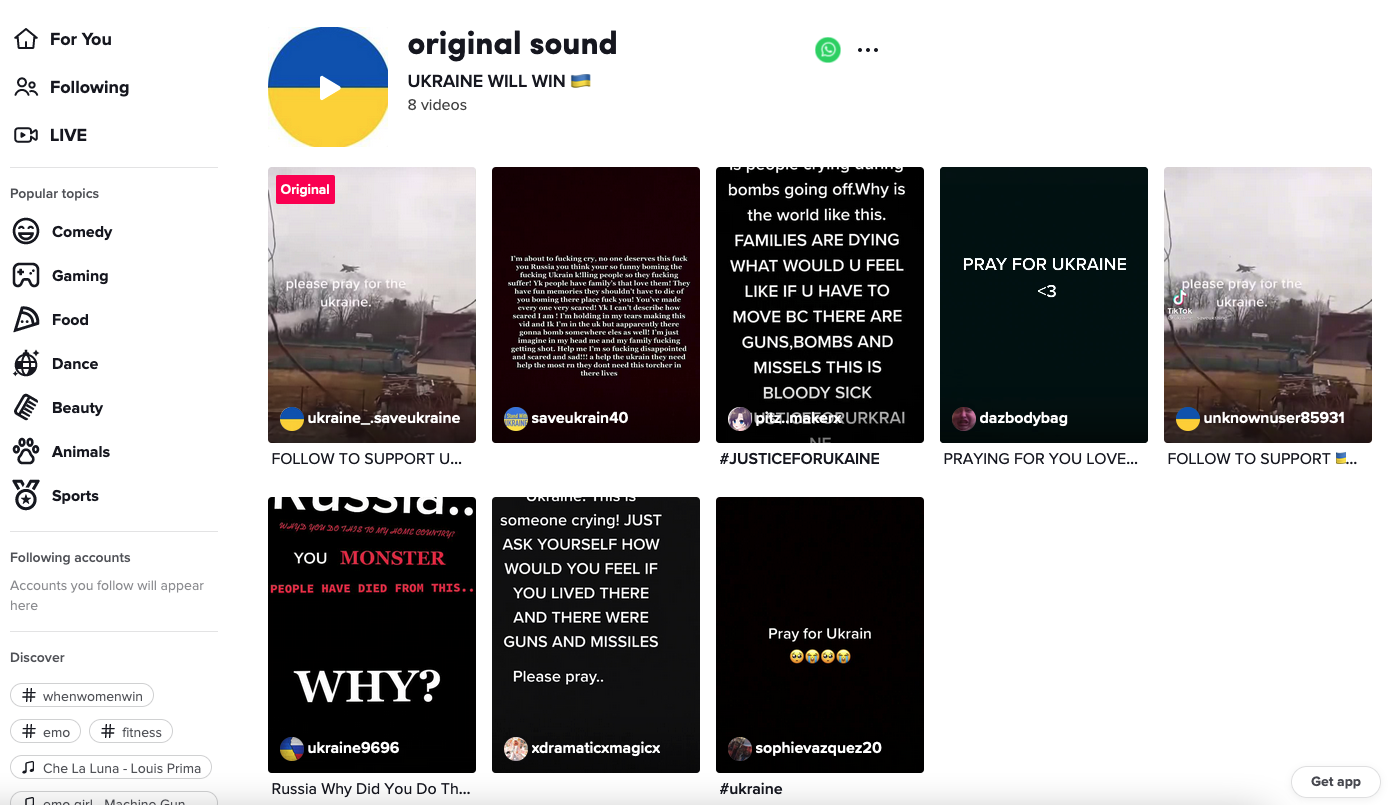

This lack of temporal context is true of reusable sounds on TikTok as well. If you click on the right-lower circle of a TikTok video that uses a stitchable sound, you are presented with a list of other videos that used that sound, as well as the original video in which the audio appeared. But there is no date and time information presented in this grid of videos. For example:

4. TikTok’s suite of built-in video editing tools allows users to manipulate video and audio in a misleading way.

When creating a post on TikTok, users are able to add background music, sound effects, filters, on-screen text, stickers and other effects to their videos. These effects can drastically change the tone, the lighting, or other major elements of the video. The platform also allows users to take the audio from any video and use it in their own uploads. While this feature is widely used in the context of making remixed dance and lipsyncing videos, it can be weaponized by media manipulators to make footage sound more authentic.When used maliciously, however, these tools can be used to fabricate footage from within a warzone or to depict a scene that never actually took place.

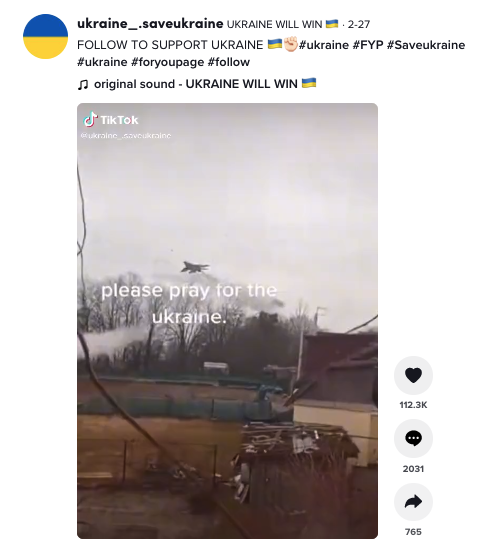

For example, the video shown below uses two effects to change its meaning. First, it uses a non-original background sound effect that has been used on 659 other videos at the time of writing. Watching the video closely shows that the gunshots captured on screen do not line up with the shots heard in the audio.

Second, the video has been overlaid with text that reads, “UKRAINE LIVE.” This leads the viewer to believe that this video was taken recently, or was even being broadcasted in real-time when it was posted. However, the fact that the soldiers are not wearing yellow-colored armbands (as Ukrainian soldiers have been doing during the 2022 Russian invasion), along with the presence of green, summer-time foliage, suggests that the clip was not captured in Ukraine just weeks into the war.

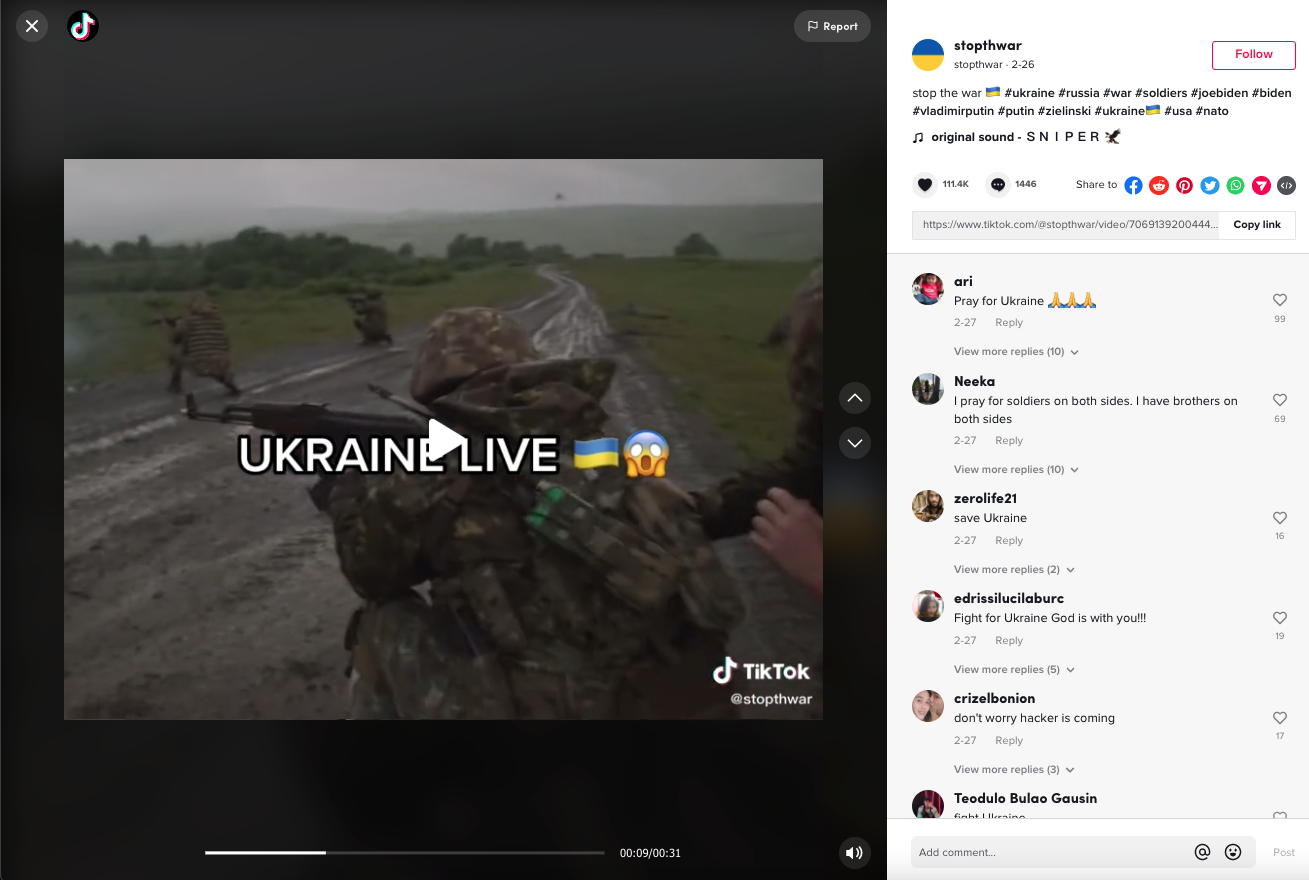

In a much more cut-and-dry example, the video below falsely claims to show “The Situation right now in Russia.” The video, which has garnered much less engagement than the previous example, combines a repurposed audio clip of people screaming and reacting to an explosion (which has been used in 57 other videos) with a shaky view from inside a nondescript building. Notably, there are no landmarks or signs seen in the video that could be used to confirm it was taken inside of Ukraine.

5. Reposting and “dueting” with another user’s videos is common.

Because it is not uncommon for TikTok users to repost other people's videos, sometimes as part of a "duet" (where the new poster reacts on screen to the original video), it can be difficult for viewers to discern where the original video came from.

For example, the below video uploaded by @blue_eyes_1223 on Feb. 24, 2022, is a repost of MSNBC reporting. The caption acknowledges “#duet with @msnbc #prayforukraine #🙏🏻 #fyp,” and the video is a copied clip from a newscast that MSNBC posted to TikTok on Feb. 23, the day before this video. The creator added “Praying for the people of Ukraine” to the video. When quickly scrolling through TikTok, the origin of the video could be missed.

6. , parody, and role-playing videos are all common genres on the platform, and viewers who aren't familiar with this specific form of comedy could mistake them as real.

Jokes, and particularly sarcasm, do not always translate over the internet. This is especially true in situations where multiple language barriers are present, and where community norms within a platform can be hard for newcomers to decipher.

Often, English-speaking TikTok users will present a silly or recontextualized video along with a serious-sounding caption, for comedic effect.

For example, the video below is captioned, “NATO on the way to Ukraine,” implying that it shows several NATO countries sending military aid to the front lines. The video, however, shows a clip from the 2010 British political satire film “Four Lions” with flag emojis of several NATO countries overlaid.

The comedic clip, contrasted with the seriousness of the caption, would be understood by most English speakers as a joke, akin to a digital political cartoon. But in the fog of war, when Ukrainians and other concerned observers are seeking accurate updates about international aid coming into Ukraine, this joke could be misinterpreted as a reference to a real aid mission.

7. TikTok pledges to label and remove misinformation, as well as take potential misinformation out of its recommendation algorithm, but as with other social media platforms, the application of this policy is inconsistent.

Below is an example of a blatantly fake video identified by the TaSC team, which claims that US troops are parachuting into Ukraine. Despite the misleading caption, users in the comments section (which had 17.5K responses at the time of writing) lists the reasons that the video is not actual footage of US troops in Ukraine.

And even though the commenters have disproven the original poster’s claims, at the time of publication, the video remains visible on TikTok and does not feature a label denoting it as containing misinformation.

TikTok does not have any specific policies pertaining to war or the current invasion, but it has removed some fake videos on an ad hoc basis.

The video above bears a striking resemblance to a separate video claiming to show Russian paratroopers dropping into Ukraine (which was actually filmed in 2015; little other information is available about it) that was debunked by several news organizations earlier this week.1 After those debunks came out, the video disappeared from the app,2 although it is unclear whether the video was removed by the original poster or TikTok moderators.

With COVID-19 , TikTok has taken more direct action against misinformation. It worked with fact-checkers at Politifact, Lead Stories, Science Feedback, and the AFP; removed or labeled posts; and redirected searches. TikTok also has specific safety policies pertaining to the depiction of sexual assualt, eating disorders, bullying, suicide/self-harm, and well-being on the platform. 3

TikTok spokeswoman Hilary McQuaide described the platform's work to moderate inauthentic and unsafe content as “newly energized in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine.”4

8. Comment sections become places for both debunks and misinformation.

Because the information presented about the provenance of a video is so sparse in the main presentation of a video on TikTok, the comment section is often where users look for more context about posts. When it comes to misleading videos, the comment section can become the place for attempted (as well as a place to debate the veracity of any given video). Commenters often list why they think a video isn’t real-time footage from inside of Ukraine, pointing to the absence of flags, the landscape, the audio, or other sources that have discussed the video (such as new sites or other social media platforms). While these comments flag doubt for other users, TikTok’s lack of “false” or “misleading” labels leaves suspicions unconfirmed.

Moreover, the way TikTok weights which comments to feature at the top of a comment section can lead to abuse and the spread of misinformation. The comment section surfaces the most popular comments first. So if a comment that spreads misinformation receives many likes, it is what users see at the top of the comment section when they go looking for more information. Ranking comments by popularity also gives media manipulators an advantage when organizing spamming campaigns across popular videos.

TikTok comment sections are a very clear example of a place that misinformation – as opposed to disinformation – has the opportunity to thrive, because when viewers leave comments guessing at the context of a video (or making a joke) these comments can then, unintentionally on the part of the person who wrote them, become a source of misinformation for future viewers of the video.

9. TikTok’s algorithm doesn’t amplify videos displaying graphic violence or gore.

Although one can find videos containing graphic violence on TikTok using certain search terms, the app’s algorithm does not typically recommend videos containing blood, injuries, corpses, or other graphic imagery on the For You Page. And these kinds of images are prohibited in TikTok’s terms of service.5 TikTok’s audiences are younger than the typical Facebook and Twitter user,6 so it is of special interest to the platform to shield its users from harmful images.

The of graphic and gory images on TikTok, as with other platforms, is done to protect users from trauma and harm and to disincentivize the glorification of violence. However well intentioned, such mitigation can risk portraying an inaccurate picture of what is happening on the ground. When bombed buildings are allowed to appear but bodies are omitted, it can give off the the impression that death and injury is not occuring.

10. TikTok has a history of being used as a tool for documenting instances of political conflict or disasters.

During times of crisis, TikTok becomes a platform for finding and sharing information faster than the mainstream press can verify and publish it. The platform has distributed on-the-ground footage from the war in Afghanistan, the Nov. 5, 2021, Astroworld tragedy, and the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, to name just three examples.7 Its livestream feature brings in observers as crises or breaking news events are unfolding, and the amount of platform moderation as well as attention from researchers and journalists is lower in comparison to other social media platforms.

This fact makes TikTok – as well as Twitter and other social media platforms – a useful terrain for various groups and people to inject political ideology, media manipulation, or advocacy into the public discourse, as researcher Abbie Richards has pointed out.8 Examples include posts about election fraud using the hashtag #stopthesteal in the lead up and months after the 2020 U.S. presidential election9 and TikTok users encouraging their followers to hoard tickets for a 2020 Donald Trump rally, in the hopes of making the rally appear to have an embarrassingly low turnout.10

Final thoughts

On the plus side, TikTok’s design makes it less vulnerable to a tactic called brigading, the act of coordinated campaigners attempting to get something to go viral, than platforms like Twitter or Facebook. TikTok bills itself as a content platform – not a social media network. It is difficult for large groups to work together on the platform to influence what appears on the For You Page, which is TikTok’s version of a somewhat randomized flow of new and trending content akin to Youtube's homepage. Each For You Page is programmed according to an ’s preferences, and relies less on which you follow unlike Twitter and Facebook feeds.

TikTok is driven by a culture that values individual creators and platform-specific microcelebrities. Therefore, TikTok influencers play a large role in the proliferation of both factual information and mis- and disinformation. And while popular TikTok personalities have an opportunity to mitigate the spread of mis- and disinformation by posting timely, accurate, local knowledge (TALK), the incentives to do so are low compared to the massive rewards of posting manipulated media.

In the rush to add information to a amid breaking news, weigh in on current events, and to stay relevant, influencers often post videos about crises using popular, but unrelated, hashtags and keywords. Influencers have great incentive to enter the discourse about a breaking news event or ongoing crisis, since these posts can boost users’ profiles; even one viral video can popularize an entire account.

Massively open platforms present benefits to society in times of war, but they also present risks. The question for technologists and researchers is how to design platforms to optimize for those benefits while mitigating the harms.

- 1 Chiara Vercellone, “Fact Check: TikTok Video First Posted in 2015, Doesn’t Show Russian Soldiers Parachuting into Ukraine,” USA TODAY, accessed March 9, 2022, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/2022/02/25/fact-check-tik…; “Fact Check-TikTok Clip of Paratrooper Recording Himself Was Not Filmed during Russian Invasion of Ukraine,” Reuters, February 25, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/article/factcheck-ukraine-russia-idUSL1N2V011G; Bethania Palma, “No, This Isn’t a Video of a Russian Paratrooper TikToking the Invasion of Ukraine,” Snopes, February 24, 2022, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/russian-paratrooper-selfie-tiktok/.

- 2 Video unavailable, accessed on March 10, 2022, https://perma.cc/GZL3-JQMU.

- 3 “COVID-19 | Safety Center,” TikTok, accessed March 8, 2022, https://www.tiktok.com/safety/en-us/covid-19/.

- 4 Bobby Allyn, “TikTok Sees a Surge of Misleading Videos That Claim to Show the Invasion of Ukraine,” NPR, February 28, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/02/25/1083255054/tiktok-sees-a-surge-of-mislea….

- 5 “Community Guidelines – Violent and Graphic Content,” TikTok, accessed March 8, 2022, https://www.tiktok.com/community-guidelines?lang=en#35.

- 6 Brooke Auxier and Monica Anderson, “Social Media Use in 2021,” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech (blog), April 7, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-202….

- 7 Abbie Richards (@abbieasr), “Alongside Stories about TikTok Being Flooded with Ukraine War Footage, I’m Seeing Academics Say ‘TikTok Has Never Been Used This Way before.’ This Is False and It Says Much More about How Academics & Journalists Have Regarded TikTok than It Says about the App. (Thread),” Tweet, Twitter, March 7, 2022, https://twitter.com/abbieasr/status/1500956940775604225.

- 8 Abbie Richards (@abbieasr), “Alongside Stories about TikTok Being Flooded with Ukraine War Footage, I’m Seeing Academics Say ‘TikTok Has Never Been Used This Way before.’ This Is False and It Says Much More about How Academics & Journalists Have Regarded TikTok than It Says about the App. (Thread),” Tweet, Twitter, March 7, 2022, https://twitter.com/abbieasr/status/1500956940775604225.

- 9 Sarah Perez, “TikTok takes down some hashtags related to election misinformation, ignores others,” Techcrunch, Nov. 5, 2020. https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/05/tiktok-takes-down-some-hashtags-relat….

- 10 Taylor Lorenz, Kellen Browning, and Sheera Frenkel, “TikTok Teens and K-Pop Stans Say They Sank Trump Rally,” The New York Times, June 21, 2020, sec. Style, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/21/style/tiktok-trump-rally-tulsa.html.