Distributed Amplification: The Plandemic Documentary

Overview

Plandemic, a 26-minute trailer video about coronavirus conspiracy theories, went viral in May 2020 because of distributed amplification. In response to its high viewership, major social media platforms moderated Plandemic and prepared for the full-length video. The platforms’ efforts slowed the spread of Indoctornation, the anticipated 75-minute movie. Indoctornation failed to achieve the virality Plandemic had.

STAGE 1: Manipulation Campaign Planning and Origins

On May 4, a little over month into the COVID-19 crisis hitting the US, a 26-minute video trailer called Plandemic hit all the major social media platforms in a coordinated launch. With high production quality, Plandemic teased an upcoming full-length film, but stood on its own as a product of planned . By misquoting physicians and researchers and by citing conspiracy theorists, Plandemic argued that the coronavirus was planned, vaccines are harmful, masks “activate” coronavirus, and that the ocean has “healing microbes.” In short, it sought to sow doubt and discredit the scientific and medical community.

Plandemic’s anti-vax messaging connected with vaccine-hesitant communities — and those with general distrust in the upcoming coronavirus vaccine,1 fears that have only grown more severe over the course of the pandemic.2 These anxieties are rooted in government distrust, distaste for pharmaceutical corporations, fallacies about historic vaccination harms, and preferences for natural remedies.3

From the start of the pandemic, these fears were repeated and amplified across social media by pre-existing online conspiracy movements. Plandemic was designed to resonate with these groups. It did. It muddied the waters, offering a counter-narrative that attempted to confuse and dissuade viewers from scientific evidence about the pandemic, the upcoming coronavirus vaccination, and public health recommendations. Within four days of hitting the internet, it had been viewed tens of millions of times.4

The video features Judy Mikovits, a discredited scientist with a PhD in biochemistry and molecular biology. She was fired from Whittemore Peterson Institute, the lab where she conducted research — and wrote a now-retracted paper in Science — on chronic fatigue syndrome.5 Mikovits has spoken at anti-vax conferences since 2014, and she published “Plague of Corruption” in April,6 wherein she portrayed herself as a whistleblower and a martyr. In her 2014 book, she made her case against the National Institute of Health personal,7 claiming that Dr. Fauci “barred her from the NIH premises”8 (a claim he denied.)9 Mikovits' academic and professional history facilitated her use of cloaked science in that it gave the video a degree of presumed credibility.

Mikki Willis produced Plandemic.10 Prior to Plandemic, the “closest he’d ever come to viral fame” was his 2015 YouTube video about buying his son a doll, which resulted in four million views and praise on local news. The next year, he helped create “Never Hillary” and “Bernie or Bust” videos during the 2016 campaign season. Willis is also the Plandemic’s funder, narrator, and the interviewer conversing with Mikovits in the video.

It was Willis who uploaded the video to , Facebook, Vimeo and Plandemic’s now-deleted website on May 4.11 The website was a tool for the video’s spread. Anticipating that the video would face content moderation, the page called on campaign participants to disseminate the video themselves: it read, “In an effort to bypass the gatekeepers of free speech, we invite you to download this interview by simply clicking the button below, then uploading directly to all of your favorite platforms.”12

This strategy, , coaches participants to re-upload banned content in an effort to circumvent platform efforts.

- 1Alec Tyson, Courtney Johnson, and Cary Funk, “U.S. Public Now Divided Over Whether To Get COVID-19 Vaccine,” Pew Research Center Science & Society (blog), September 17, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/17/u-s-public-now-divided-over-whether-to-get-covid-19-vaccine/.

- 2Sarah Zhang, “COVID-19 Is a Perfect Storm for Vaccine Skepticism,” The Atlantic, May 24, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2020/05/covid-19-vaccine-skeptics-conspiracies/611998/.

- 3Anna Kata, “Anti-Vaccine Activists, Web 2.0, and the Postmodern Paradigm – An Overview of Tactics and Tropes Used Online by the Anti-Vaccination Movement,” Vaccine, Special Issue: The Role of Internet Use in Vaccination Decisions, 30, no. 25 (May 28, 2012): 3778–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.112.

- 4Alex Mahadevan, “Fact-Checking ‘Plandemic,’ a Documentary Full of False Conspiracy Theories about the Coronavirus,” Poynter (blog), May 8, 2020, https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2020/plandemic-video-fact-check/.

- 5Jane Lytvynenko, Ryan Broderick, and Craig Timberg, “Coronavirus Pseudoscientists And Conspiracy Theorists,” BuzzFeed News, May 21, 2020, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/janelytvynenko/coronavirus-spin-doctors.

- 6Davey Alba, “Virus Elevate a New Champion,” The New York Times, May 9, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/09/technology/plandemic-judy-mikovitz-coronavirus-disinformation.html.

- 7Alex Kasprak, “Was a Scientist Jailed After Discovering a Deadly Virus Delivered Through Vaccines?,” Snopes, December 8, 2018, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/scientist-vaccine-jailed/.

- 8Lytvynenko, Broderick, and Timberg, “Coronavirus Pseudoscientists And Conspiracy Theorists.”

- 9Lytvynenko, Broderick, and Timberg.

- 10Alba, “Virus Conspiracists Elevate a New Champion.”

- 11Sheera Frenkel, Ben Decker, and Davey Alba, “How the ‘Plandemic’ Movie and Its Falsehoods Spread Widely Online,” The New York Times, May 20, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/20/technology/plandemic-movie-youtube-facebook-coronavirus.html.

- 12"Plandemic," May 5, 2020, accessed via web.archive.org, https://web.archive.org/web/20200506093510/https://plandemicmovie.com/.

STAGE 2: Seeding Campaign Across Social Platforms and Web

Their instructions worked. Media Matters’ Alex Kaplan says, “you could see the impact: dozens of reuploads of the video on YouTube — even after they tried to remove the original — and shares of it on other platforms.”1

In addition to reuploads, shares across different blogs and online communities made Plandemic go viral. Internet researcher Erin Gallagher “found that posts referencing it appeared most often in groups devoted to QAnon, anti-vaccine misinformation, and conspiracy theories in general.”2 (Gallagher now works with the Technology and Social Change team at Shorenstein but was independent at the time of this research.)

Gallagher noted that Plandemic “spread from YouTube to Facebook thanks to highly active QAnon and conspiracy-related Facebook groups with tens of thousands of members which caused a massive cascade.”3 She further emphasized that these platforms “were instrumental in spreading viral .”4

MIT Technology Review’s Abby Ohlheiser laid out the tactics that drove views, describing how activists pursued interviews with “mainstream YouTubers” and “latched on to existing trends, encouraged their fans to amplify their messages, and built presences on every social platform they can find.”5 Its removal made Plandemic more popular — leading to censorship claims, increased attention, trending hashtags, and media exposure.6

Plandemic created a successful campaign by employing scarcity marketing tactics (i.e. “see it before it’s gone”) and a narrative attractive to groups outside of the scientific mainstream, suspicious of vaccines, and/or repudiating coronavirus precautions. As Research Director Joan Donovan explained to NBC, “[in] knowing they will be removed from the major platforms, they create a hype cycle around the piece of content, which would probably only get marginal engagement if it was uploaded to a regular website.”7

On May 5, Plandemic was shared with the text “Exclusive Content, Must Watch”8 by a Facebook group dedicated to QAnon (~25K members); by Dr. Christiane Northrup, a women’s health physician and prominent anti-vaxxer whose “status as a celebrity doctor made her endorsement of ‘Plandemic’ powerful”9 (to her ~500K Facebook followers); on Facebook by Reopen Alabama (~36K members) and then by other Reopen groups; and by MMA fighter and anti-vaxxer Nick Catone (to his ~70K Facebook followers), who led with “Watch this before it’s taken down.”10

- 1Frenkel, Decker, and Alba, “How the ‘Plandemic’ Movie and Its Falsehoods Spread Widely Online.”

- 2Casey Newton, “How the ‘Plandemic’ Video Hoax Went Viral,” The Verge, May 12, 2020, https://www.theverge.com/2020/5/12/21254184/how-plandemic-went-viral-facebook-youtube.

- 3Newton, “How the ‘Plandemic’ Video Hoax Went Viral.”

- 4Newton.

- 5Abby Ohlheiser, “Facebook and YouTube Are Rushing to Delete ‘Plandemic,’ a Conspiracy-Laden Video,” MIT Technology Review, May 7, 2020, https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/05/07/1001469/facebook-youtube-plandemic-covid-misinformation/.

- 6Ohlheiser, “Facebook and YouTube Are Rushing to Delete ‘Plandemic,’ a Conspiracy-Laden Video.”

- 7Brandy Zadrozny and Ben Collins, “As ‘#Plandemic’ Goes Viral, Those Targeted by Discredited Scientist’s Crusade Warn of ‘Dangerous’ Claims,” NBC News, May 7, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/plandemic-goes-viral-those-targeted-discredited-scientist-s-crusade-warn-n1202361.

- 8Frenkel, Decker, and Alba, “How the ‘Plandemic’ Movie and Its Falsehoods Spread Widely Online.''

- 9Frenkel, Decker, and Alba.

- 10Ibid.

STAGE 3: Responses by Industry, Activists, Politicians, and Journalists

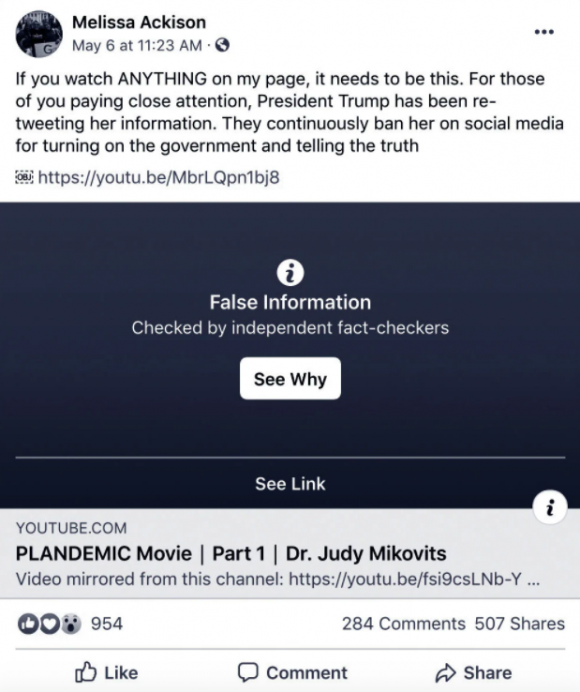

On May 6, by Melissa Ackison, a Republican candidate for Ohio’s 26th District Senate (~20K followers) pleaded on Facebook: “If you watch ANYTHING on my page, it needs to be this.”1

Facebook posts to followers of QAnon, Dr. Northrup, the Reopen movements, Catone, and Ackison — and the engagement of these groups with the video — led to the “massive cascade”2 that Gallagher describes. Within their posts, the authors’ captions emphasized the urgency and importance of watching Plandemic.3

On May 7, BuzzFeed reported on Plandemic and its falsehoods, signifying the conspiratorial video had made it to mainstream media. Moreover, BuzzFeed’s article was shared to Occupy Democrats and 62 other Facebook pages — introducing Plandemic to groups who may not have seen it yet.4

The Atlantic,5 NPR,6 Wall Street Journal,7 Science,8 and BBC News9 are among the publications that published Plandemic articles within the first week of its release. Advocacy groups — including global health, pro-vaccine, and pro-science groups — also covered Plandemic.

As word (and links) continued to spread, NBC News reported that Plandemic “has been shared by celebrities, including the comedian Larry the Cable Guy, NFL players and with millions of followers.”10 In the same article, George Washington University’s David Broniatowski discussed Plandemic’s resonance — and hazard — across normally unaligned groups: "The danger with movies like this is that they can weave all of the disparate streams into a common narrative, building a coalition for political and collective action, even when the reasons for this coalition aren't universally shared.”11

In addition to the rapid spread of Plandemic, Mikovits, the video’s protagonist, became a popular figure, receiving a disproportionate amount of media coverage. The New York Times’ Davey Alba, in an article that brought Mikovits to the attention of Times readers, describes Mikovits’ new fame: “She has become a darling of far-right publications like The Epoch Times and The Gateway Pundit.”12 Prior to the Plandemic and “Plague of Corruption,” Mikovits’ online mentions were rare, but by April, she was mentioned about 800 times a day, spiking as high as 14,000 a day by May 9th.13

- 1Ibid.

- 2Newton, “How the ‘Plandemic’ Video Hoax Went Viral.”

- 3Frenkel, Decker, and Alba, “How the ‘Plandemic’ Movie and Its Falsehoods Spread Widely Online.”

- 4Frenkel, Decker, and Alba.

- 5 Joe Pinsker, “If Someone Shares the ‘Plandemic’ Video, How Should You Respond?,” The Atlantic, May 9, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2020/05/plandemic-video-what-to-say-conspiracy/611464/.

- 6Scott Neuman, “Seen ‘Plandemic’? We Take A Close Look At The Viral Conspiracy Video’s Claims,” NPR.org, May 8, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/05/08/852451652/seen-plandemic-we-take-a-close-look-at-the-viral-conspiracy-video-s-claims.

- 7 Georgia Wells, “Doctors Are Tweeting About Coronavirus to Make Facts Go Viral,” Wall Street Journal, May 15, 2020, sec. Tech, https://www.wsj.com/articles/doctors-are-tweeting-about-coronavirus-to-make-facts-go-viral-11589558880.

- 8Martin Enserink and Jon Cohen, “Fact-Checking Judy Mikovits, the Controversial Virologist Attacking Anthony Fauci in a Viral Conspiracy Video,” Science, May 8, 2020, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/05/fact-checking-judy-mikovits-controversial-virologist-attacking-anthony-fauci-viral.

- 9“Coronavirus: ‘Plandemic’ Virus Conspiracy Video Spreads across Social Media,” BBC News, May 8, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-52588682.

- 10Zadrozny and Collin, “As ‘#Plandemic’ Goes Viral, Those Targeted by Discredited Scientist’s Crusade Warn of ‘Dangerous’ Claims.”

- 11Zadrozny and Collins, “As ‘#Plandemic’ Goes Viral, Those Targeted by Discredited Scientist’s Crusade Warn of ‘Dangerous’ Claims.”

- 12Alba, “Virus Conspiracists Elevate a New Champion.”

- 13Alba.

STAGE 4: Mitigation

By May 6, Facebook, YouTube, and had removed Plandemic. In statements to The Washington Post, Facebook explained “[s]uggesting that wearing a mask can make you sick could lead to imminent harm, so we’re removing the video;” YouTube said it prohibits “content that includes medically unsubstantiated diagnostic advice for covid-19;” and Vimeo emphasized it “stands firm in keeping our platform safe from content that spreads harmful and misleading health information. The video in question has been removed by our Trust & Safety team for violating these very policies.”1 Twitter implemented de-indexing, saying it had “removed the hashtags #PlagueofCorruption and #PlandemicMovie from its searches and trends sections.”2 Mashable reported that allowed the link to remain on the site because users were correcting the information and including the video for context.3

Mainstream news outlets provided critical press, profiling the team, plotting Plandemic’s timeline of views, contextualizing it within the national vaccine conversation, and making platform action known. Fact-checking organizations debunked baseless arguments, reattributed misquoted statements, and gave context to mostly or partially false statements.4

To counter Mikovits’ claims, Science stated that vaccines save lives and that there is no evidence that coronavirus was planned, is mask-activated, or can be cured by nature.5

Plandemic has also been fact-checked by PolitiFact,6 FactCheck,7 MedPage Today,8 and Snopes.9

- 1Travis M. Andrews, “Facebook and Other Companies Are Removing Viral ‘Plandemic’ Conspiracy Video,” Washington Post, May 7, 2020, http://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/05/07/plandemic-youtube-facebook-vimeo-remove/.

- 2Andrews, “Facebook and Other Companies Are Removing Viral ‘Plandemic’ Conspiracy Video.”

- 3Matt Binder, “Twitter Takes Action against Sequel to Coronavirus Conspiracy Film ‘Plandemic,’” Mashable, August 18, https://mashable.com/article/twitter-plandemic-sequel/.

- 4Daniel Funke, “Fact-Checking ‘Plandemic’: A Documentary Full of False Conspiracy Theories about the Coronavirus,” PolitiFact, May 7, 2020, https://www.politifact.com/article/2020/may/08/fact-checking-plandemic-documentary-full-false-con/; Angelo Fichera et al., “The Falsehoods of the ‘Plandemic’ Video,” FactCheck.Org (blog), May 8, 2020, https://www.factcheck.org/2020/05/the-falsehoods-of-the-plandemic-video; Mikhail Varshavski, DO, “Point-by-Point ‘Plandemic’ Smackdown,” MedPage Today, May 14, 2020, https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/covid19/86487; Team Snopes, “Fact Check Collection: Snopes Debunks ‘Plandemic,’” Snopes.com, May 11, 2020, https://www.snopes.com/collections/plandemic/.

- 5Enserink and Cohen, “Fact-Checking Judy Mikovits, the Controversial Virologist Attacking Anthony Fauci in a Viral Conspiracy Video.”

- 6Funke, “Fact-Checking ‘Plandemic’: A Documentary Full of False Conspiracy Theories about the Coronavirus.”

- 7Fichera et al., “The Falsehoods of the ‘Plandemic’ Video.”

- 8Varshavski, DO, “Point-by-Point ‘Plandemic’ Smackdown.”

- 9Team Snopes, “Fact Check Collection: Snopes Debunks ‘Plandemic.’”

STAGE 5: Adjustments by Manipulators to New Environment

As instructed, campaign participants reposted clips from major platforms onto lesser-known . Poynter reported that one such site, , had Plandemic clips with more than 64,000 views by May 14.1 Less than a week later, BitChute’s top search result for “Plandemic” had over 1.6 million views, according to CBC.2

Beyond migrating to minor platforms, Plandemic adjusted its campaign tactics by releasing Indoctornation, a second video on August 18, three months after the first.

Unlike the trailer, Indoctornation wasn’t a surprise bombshell; it was expected. Before it launched, it was promoted “at least 887 times on Facebook, from pages with hundreds of thousands of followers,”3 writes The Verge’s Casey Newton. To market Indoctornation, the creators again relied on its anticipated removal.

Indoctornation was uploaded to https://plandemicseries.com/, which was built for its release and now includes the trailer Plandemic. The trailer’s now-deleted website was https://plandemicmovie.com/ — now an available domain. The new website directs campaign participants to:

“(1) Download the videos

(2) Upload Everywhere

Give the video your own title so that it’s harder for the censors to find it

(3) Invite others to watch and share

The Plandemic series is 100% people powered. You are the distributor. Please share far and wide!”4

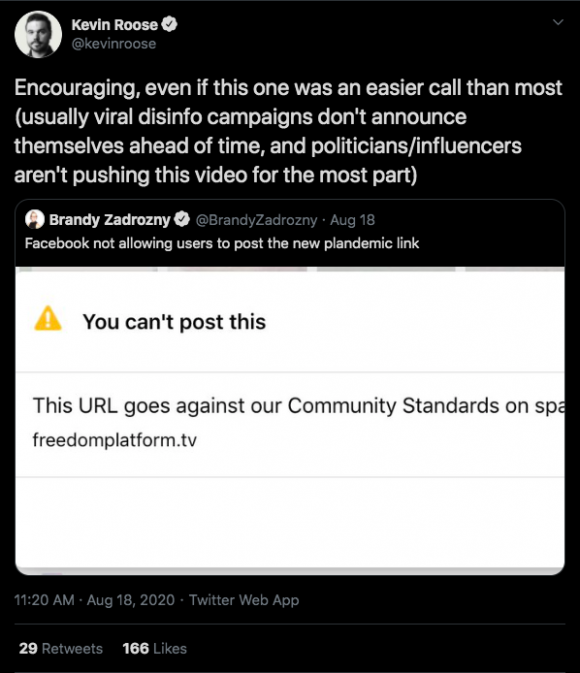

These instructions were meant to circumvent moderation by major platforms. Social media companies did respond to Indoctornation, as expected. Prior to its release, LinkedIn deleted an account Indoctornation.5 Facebook prohibited users from posting the link. Twitter allowed the link, but warned it was “potentially spammy or unsafe.”6 Mashable reported that Twitter users who try to use the link are met with CDC information.7

In response to Facebook the link, The New York Times’ tech columnist Kevin Roose tweeted, “Encouraging, even if this one was an easier call than most (usually viral disinfo campaigns don't announce themselves ahead of time, and politicians/influencers aren't pushing this video for the most part).”8

As a result, Indoctrination received far less attention and views. By taking proactive action, major platforms did not facilitate the transmission of the documentary and were able to avoid a repeat of Plandemic’s virality. That being said, both Indoctornation and Plandemic continue to live on smaller platforms, easily accessible to those searching for it.

- 1Aiyana Ishmael, “‘Plandemic’ Recirculates after Platforms Say They Took It Down,” Poynter (blog), May 18, 2020, https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2020/plandemic-recirculates-after-platforms-say-they-took-it-down/.

- 2Andrea Bellemare, Katie Nicholson, and Jason Ho, “How a Debunked COVID-19 Video Kept Spreading after Facebook and YouTube Took It Down,” CBC, May 21, 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/alt-tech-platforms-resurface-plandemic-1.5577013.

- 3Casey Newton, “Platforms Successfully Stopped a COVID Conspiracy Video from Going Viral,” The Verge, August 19, 2020, https://www.theverge.com/interface/2020/8/19/21373820/plandemic-indoctornation-facebook-youtube-twitter-removal-block-covid-hoax-block.

- 4“Plandemic: Indoctornation,” Plandemic Series, accessed September 29, 2020, https://plandemicseries.com/.

- 5Newton, “Platforms Successfully Stopped a COVID Conspiracy Video from Going Viral.”

- 6Newton, “Platforms Successfully Stopped a COVID Conspiracy Video from Going Viral.”

- 7Binder, “Twitter Takes Action against Sequel to Coronavirus Conspiracy Film ‘Plandemic.’”

- 8Kevin Roose (@kevinroose), “Encouraging, even if this one was an easier call than most (usually viral disinfo campaigns don't announce themselves ahead of time, and politicians/influencers aren't pushing this video for the most part),” Twitter, August 18, 2020, https://twitter.com/kevinroose/status/1295787696657272833.

Cite this case study

Jennifer Nilsen, "Distributed Amplification: The Plandemic Documentary," The Media Manipulation Case Book, July 7, 2021, https://casebook-static.pages.dev/case-studies/distributed-amplification-plandemic-documentary.