Milk Tea Alliance: From Meme War to Transnational Activism

Overview

The Milk Tea Alliance is an online coalition of youth mainly from Thailand, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Myanmar. It originated in April 2020 after pro-Chinese Communist Party (CCP) internet accounts launched an online campaign to harass a Thai celebrity and his supporters. Soon, a loosely coordinated group of young, primarily Southeast Asian, pro-democracy netizens came together to offset the pro-CCP activities. This culminated in a meme war on between the two sides.

Once the with the pro-CCP supporters ended, the online activists began to coalesce as a group to share petitions and activist-oriented campaign materials under the banner of “Milk Tea Alliance.” Today, the Milk Tea Alliance is a loose international network of youth engaged in , using the hashtag #MilkTeaAlliance, to battle what they view as authoritarianism worldwide, whether targeting the CCP or their own governments. The #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag and coalition has been redeployed and adaptated numerous times and ways since its original purpose in Thailand, as Stage 5 of this case documents.

Because of the nature of this campaign, the stages of the media manipulation life cycle often overlap. Redeployments and adaptations of the hashtag and may fall chronologically very close to one another. Below, we try to delineate what was part of the original campaign, which actions were a response to the campaign, and which were subsequent readjustments and redeployments by campaign operators. As a result, the stages here are not purely chronological; they reflect the nature of the activity relative to the original #MilkTeaAlliance meme war.

Background

Officially, the Milk Tea Alliance was sparked by pro-Chinese Communist Party netizens who swarmed a Thai actor and his girlfriend, triggering an online response in their defense. But there are underlying issues that explain its rapid adoption across Asia – namely territorial claims about Taiwan and Hong Kong combined with fears of encroaching authoritarianism and CCP influence in Asia.

Taiwan, although independently governed since 1949, is still considered by CCP leaders as part of “One-China.” They vow to eventually unify Taiwan with the Chinese mainland – a position Taiwan’s government rejects.1 As a result, these two governments have a tense relationship, with Taiwan asserting its independence from China and China maintaining that the island is part of its territory.

Hong Kong, a “special administrative region” of China, is in a similarly tense and ambiguous relationship with mainland China. It has been free to manage its own internal affairs under a national unification policy that dates back to the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration when the British returned the territory to China. However, in recent years, Beijing has exerted increasing control over Hong Kong, leading to numerous ongoing protests there. This pro-democracy movement has, in turn, provoked further crackdowns from Beijing.2 Beyond these two territorial conflicts, pro-democracy and youth activists in Asia proximate to China demonstrate growing concern that its perceived authoritarian means of governance are having an undue influence on their own countries.3 Combined with their opposition to increasingly restrictive and illiberal actions by their own governments, the Milk Tea Alliance symbolizes much of this frustration.4

- 1Lindsay Maizland, “Why China-Taiwan Relations Are So Tense,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 10, 2021, archived on Perma.cc, perma.cc/P5G2-RDBF.

- 2 Chris Buckley, Vivian Wang and Austin Ramzy, “Crossing the Red Line: Behind China’s Takeover of Hong Kong,” The New York Times, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/U4JE-4BS

- 3 Leela Jacinto, “‘Milk Tea Alliance’ blends Asian discontents – but how strong is the brew?,” France 24, January 3 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/T2E4-MUG8; Mia Ping-Chieh Chen International 'Milk Tea Alliance' Faces Down Authoritarian Regimes,” Radio Free Asia, October 14 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/5X9L-9HT2

- 4 The Milk Tea Alliance draws its name from a shared affinity for milk tea. The beverage is found in many cultures, but ingredients and preparation differ regionally. Each member of the Milk Tea Alliance has their own local variation of the drink. Taiwan is known as the birthplace of bubble tea, a milk tea that features tapioca. Hong Kong is known for having extremely creamy milk tea, made by simmering tea leaves with condensed and/or evaporated milk, which dates back to British colonial rule. Thailand’s orange-colored Thai iced tea is milk tea mixed with a special dye. The hashtag #MilkTeaIsThickerThanBlood is used frequently to refer to the culinary bond between these three regions as well as other places that also share a love for the popular drink.

Stage 1: Manipulation campaign planning and origins

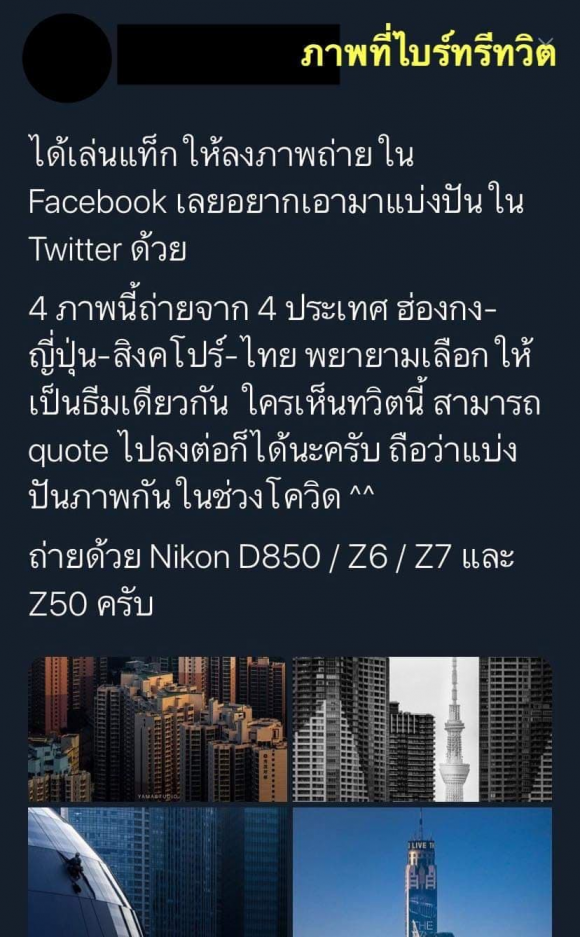

Over the weekend of April 4, 2020, Thai actor Vachirawit Chivaaree, also known as “Bright,” liked a Thai photographer’s tweet.1 The tweet by account @Yamastdio included a picture of Hong Kong alongside pictures of other places, and the caption referred to all places pictured in the tweet as “countries.”2 Some Chinese Twitter users perceived Bright’s “like” as a statement about Hong Kong’s independence. Circumventing their country’s internet firewall – which blocks Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook – they bombarded Bright on those platforms, demanding an apology, calling for a boycott of his TV show, insulting his appearance, and making other derogatory comments.3

- 1Khadsod Online, April 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/K92G-NZXS

- 2Taiwan News, April 13, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/CF3W-TG8R

- 3PROTECT BRIGHT (@ProtectBright), “ this account under TARGETED , OFFENSIVE AND DISRESPECFUL, HATEFUL/SPAM Do not Engage Faustgummi https://twitter.com/Bunnyyy84722877?s=09…i told you to smile https://twitter.com/whydxntyousmile?s=09” Twitter, July 16 2020, archived on https://perma.cc/23EB-XWMK; Mia Ping-Chieh Chen International 'Milk Tea Alliance' Faces Down Authoritarian Regimes,” Radio Free Asia, October 14 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/5X9L-9HT2; Laignee Barron, “'We Share the Ideals of Democracy.' How the Milk Tea Alliance Is Brewing Solidarity Among Activists in Asia and Beyond,” Time October 28 2020, archived on perma.cc,https://perma.cc/GCM8-S5UC

Figure 1: Chivaaree (@Brightvc) likes a tweet by a Thai photographer (@Yamastdio) that referred to Hong Kong as a country. Archived on Perma.cc, Keoni Everington, “Thais use humor to defeat Chinese in Twitter war,” Taiwan News, April 13, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/4BZ2-5D6W. Credit: Screenshot by TaiwanNews.

Bright apologized on Twitter on April 9, 20201 – four or five days after the post that sparked Chinese internet users’ fury. “I feel so sorry about my thoughtless retweet that I only saw the pictures and retweet. Next time I will be more careful about this,” he said. Still, pro-CCP netizens continued to harass the actor online.

- 1Bright (@bbrightvc), “i’m feel so sorry about my thoughtless retweet too , i only saw the pictures and did not read the caption clearly. Next time there will be no mistake like this again.,” Twitter, April 9, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, perma.cc/LRB4-QAKP.

Figure 2: Chivaaree (@Brightvc) apologizes for retweeting a post by a photographer that referred to Hong Kong as a country. Archived on Perma.cc, archived on perma.cc, https://perma.cc/R3MP-5DT3. Credit: Screenshot by TaSC.

Figure 3: Photographer @Yamastdio apologizes for calling Hong Kong a country and reposts his original photos, with an edited caption calling the places “locations”, rather than “countries.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/AFR5-LTCC. Credit: Screenshot by dailycpop.

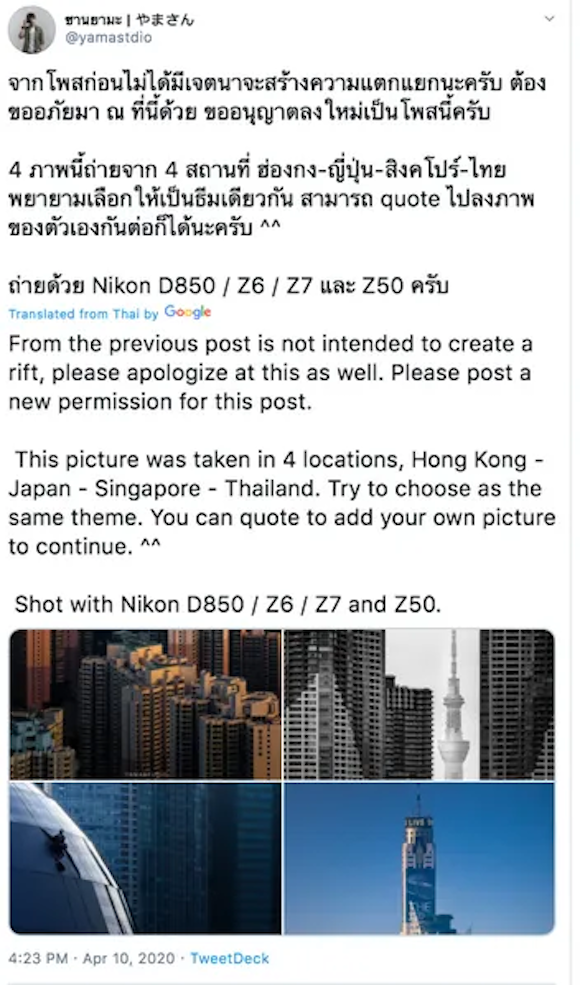

They also began targeting his girlfriend, Thai celebrity Weeraya “New” Sukaram, whom the CCP supporters believed had also insulted China, and in particular Chinese women, in a now-deleted post years before. On Sept. 15, 2017, Bright had commented on Instagram that New looked as pretty as a “Chinese girl,” to which New replied with a correction: She was pretty like a “Taiwanese woman.”1 Chinese nationalists also accused New of retweeting a tweet questioning whether COVID-19 originated in a Chinese laboratory, known as the lab theory, but this retweet has since been deleted from her Twitter feed.2

Using the hashtag #nnevvy, which is New’s Instagram handle, pro-CCP users in 2020 began demanding that she apologize, trolled her social media accounts, and insulted Thai social media users using memes to make fun of the Thai king and government policies.3 According to Twitter, the #nnevvy hashtag appeared 11 million times on the platform from April 2020 to April 2021.4 Al Jazeera reported that it had drawn 4.6 billion views across over 1.4 million posts on Weibo, China’s state-sponsored version of Twitter.5

- 1Nnevvy, “History of Milk Tea Alliance (Part 1)”, . Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/TCS5-2XJB

- 2 “China-Thailand coronavirus social media war escalates,” Al Jazeera, April 14 2020, archived on Perma.cc, perma.cc/Q7JP-RYDV

- 3 Lauren Teixeira, “Thais Show How to Beat China’s Online Army,” Foreign Policy, April 17 2020, archived on Perma.cc, perma.cc/YW9R-4KZE; James Griffith, “Nnevvy: Chinese troll campaign on Twitter exposes a potentially dangerous disconnect with the wider world,” CNN, April 14 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/2RTU-K4MX

- 4 Twitter Public Policy (@@Policy), “We have seen more than 11 million Tweets featuring the #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag over the past year. Conversations peaked when it first appeared in April 2020, and again in February 2021 when the coup took place in Myanmar:,” Twitter, April 7, 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/398R-ZLWW

- 5 Dan McDevitt, “‘In Milk Tea We Trust’: How a Thai-Chinese Meme War Led to a New (Online) Pan-Asia Alliance,” The Diplomat, April 18, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/GN2L-E4XW

Figure 4: New (@nnevvy) corrects Chivaaree in her Instagram comments, saying she looks “pretty” like a Taiwanese girl, not a Chinese girl. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/A7DS-8UAB. Credit: Screenshot by Taiwan News.

Figure 5: A screenshot of Chivaaree (Bright) liking a post that said COVID-19 originated from a lab in Wuhan. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/V5WQ-29XD. Credit: Screenshot by Twitter user @wearytolove.

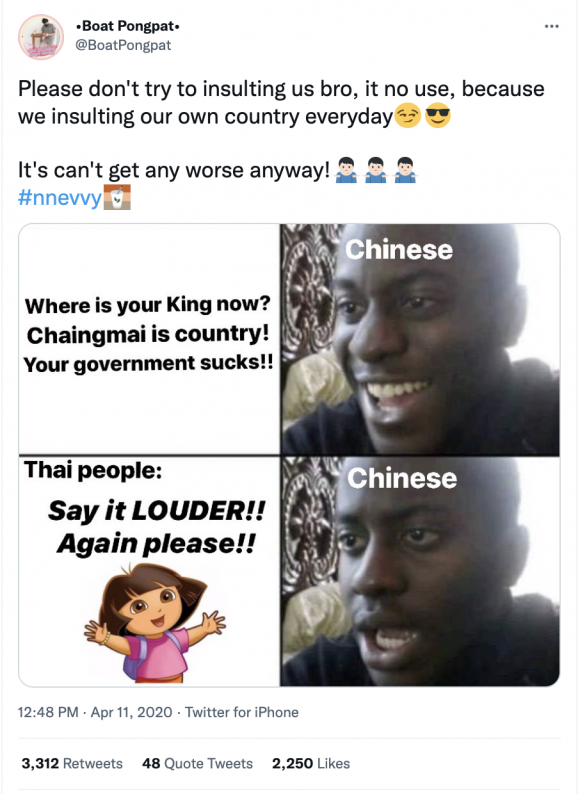

The pro-CCP attacks on Bright and New triggered a backlash from Thai netizens and fans of the two celebrities, who countered with their own memes. During the same weekend that CCP supports began to attack Bright, Thai users reclaimed the #nnevvy hashtag and used it to “dunk” on CCP supporters by singing self-deprecating humor about their own country. This form of community mitigation made it difficult for the pro-CCP accounts to troll the Thai netizens, as they often created more popular memes to make fun of their own country – and of China, too (see Figure 6 and 7 below).

Figure 6: A meme on Twitter where Thai user @BoatPongpat agreed with the Chinese criticism of their government. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/J4XV-4SGF. Source: Screenshot by TaSC.

Figure 7: Another meme where Thai people agreed with Chinese criticism of their government. Archived on perma.cc, https://perma.cc/XV2A-P34Y. Source: @nnevvymeme Facebook page.

Soon after, other Twitter users, primarily from Hong Kong and Taiwan, joined this counter-CCP campaign. On April 11, 2020, the Taiwanese blogger Emmy Hu posted in Chinese to her 100,000-plus followers on Facebook that Thai netizens were fighting CCP supporters online, in support of Taiwan's independence and Hong Kong’s autonomy. She encouraged her followers to search the #nnevvy hashtag on Twitter to find the meme war. Her post gained 42,000 likes and 14,000 shares as of March 2022.1 Normally, Hu’s posts – which tend to cover her political opinions and daily interactions – receive less than 5,000 likes and 100 shares.

On April 13, 2020, the first uses of #MilkTeaAlliance emerged on Twitter, often in conjunction with the #nnevvy hashtag. One of the first such tweets to achieve some traction (over 400 retweets) immediately made the connection between multiple Asian countries showing a map of the various milk teas in the region encircling China and a call to “form the #MilkTeaAlliance” (Figure 8 below).2 By April 15, 2020, the hashtag had reached trending status in Thailand.3

- 1Emmy Hu, “欸欸泰國為台灣開戰了超好笑的,” Facebook, April 11, 2020, archived via Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7362-EUC6.

- 2 Wen lui (@wenliunyc) “Best map on the #MilkTeaAlliance so far,” Twitter, April 15, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/KW5A-JMJ3

- 3Patpicha Tanakasempipat, “Young Thais join 'Milk Tea Alliance' in online backlash that angers Beijing,” Reuters, April 15, 2020, archived on perma.cc, https://perma.cc/RC4M-3WYN

Figure 8: A meme mapping the various regional members of the Milk Tea Alliance and their respective versions of milk tea. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/NYJ2-AZR9. Source: @wenliunyc on Twitter.

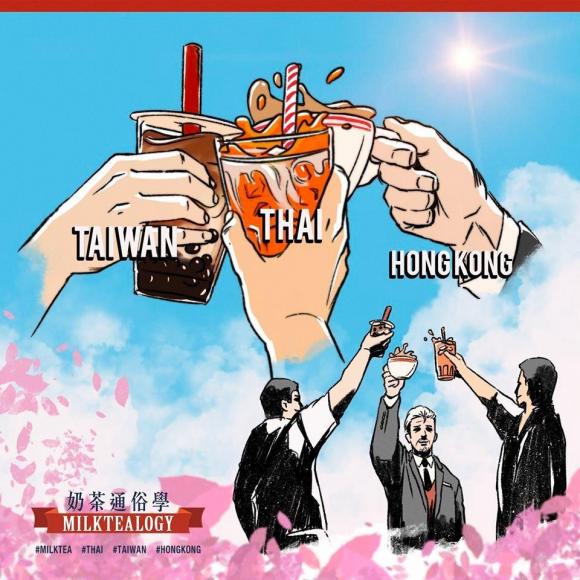

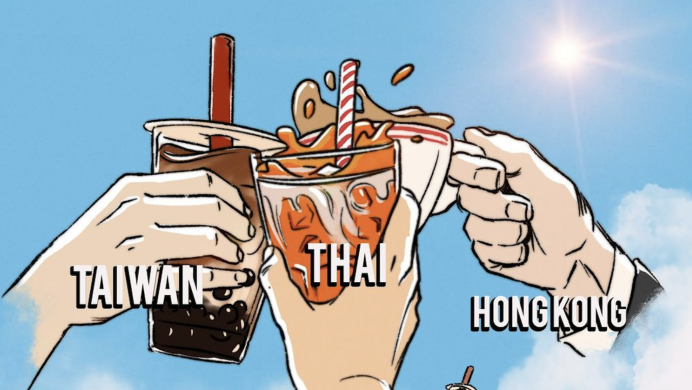

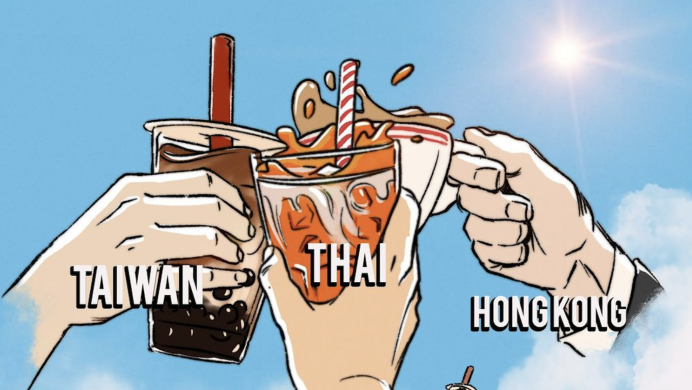

#MilkTeaAlliance also migrated from Twitter to other social media platforms. For example, on April 14, 2020, amidst the ongoing meme war against the pro-CCP accounts on Twitter, a Facebook page called “Milktealogy,” which was created in March 2014 to share apolitical memes celebrating milk tea, posted a photo of three people toasting with milk tea (Figure 8). One milk tea was Taiwanese, one was Thai and one was from Hong Kong – and the image was accompanied by the hashtag “#milktea #nnevvy,” referencing the meme war then underway.1 Nnevvy, a Facebook page started on April 12, 2020 by a social media marketer to post anti-CCP memes, reposted this image on April 14 with the caption “I like how milk tea unite us <3.” Its followers agreed. The post received more than triple the average number of engagement that most Nnevvy Facebook page posts had, with 18,000 likes, 513 comments, and 2,300 shares.2

From this point on, many #nnevvy posters referred to their coalition as the “Milk Tea Alliance” on Facebook and Twitter. April 15, 2020, is also the date that the #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag appeared in English-language media for the first time, in an article by Reuters.3 After the hashtag received thousands of tweets in the first two days of its inception, Reuters published a second article on the movement the next day, and called it a movement that united people from Thailand, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.4

- 1奶茶通俗學 Milktealogy, “#milktea #nnevvy” Facebook, April 14 2020, https://perma.cc/N939-HNGU

- 2Nnevvy, “I like how milk tea unite us Source” https://m.facebook.com/story.phpstory_fbid=1565079953649581&id=28365566… #nnevvy,” Facebook, April 14 2020, https://perma.cc/PUS5-2DVD

- 3Patpicha Tanakasempipat, “Young Thais join 'Milk Tea Alliance' in online backlash that angers Beijing,” Reuters, April 15 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/EEN3-ELT9

- 4Ibid.

Figure 9: A meme depicting the different milk teas of Taiwan, Thailand, and Hong Kong. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/47VE-WTSB. Credit: @HongKon93459885 Twitter account.

Figure 10: A meme of Thailand, Hong Kong, and Taiwan being united by milk tea. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/L5A7-SPCS. Credit: Joshua Wong (@joshuawong).

Stage 2: Seeding the campaign across all social platforms and the web

Following the dissemination of the hashtag around April 14th, #MilkTeaAlliance spread across Facebook and Twitter in English, Thai, and Chinese. The Alliance’s ability to be inclusive and adapt to different wedge issues helped expand its reach and membership. International and aimed at cross-border solidarity from the onset, the online alliance quickly expanded to countries such as Myanmar, Philippines, and even, in a rare non-Asian example, Belarus.1 The administrator of the Nnevvy Facebook page is based in Malaysia. And one of the largest Milk Tea Alliance Twitter accounts, @AllianceMilkTea (68.4K followers) is based in Myanmar.

The national origins of the two most prominent Milk Tea Alliance accounts illustrates how the sprawling network expanded beyond its three original regions by activating young netizens deeply invested in promoting democracy in their own countries and regionally. The accounts actively recruit global page administrators as a way to diversify the membersship of this expanding online alliance. One post on the Nnevvy Facebook page advertises that the group is looking “for at least one person from Thailand/Taiwan/Hong Kong/Philippines/Vietnam/India/US/Australia/South Korea/ Malaysia and Singapore.” It states that people from other countries are also welcome to join, with skills and requirements including language translation from English to their local language and brainstorming on how to improve the Milk Tea Alliance.2

In addition to the #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag becoming a pro-democracy call to action, the memes it gave rise to – those making fun of the CCP, mocking its internet firewall, and its supporters – continued to spread across affiliated Facebook groups and Twitter accounts. Sites of particular #MilkTeaAlliance meme activity include the Nnevvy page on Facebook (92K followers as of March 2022) and, on Twitter, the accounts @AllianceMilkTea (68.3K), and @MilkTeaMM_MTAM (52K). Multiple hashtags are generally used along with #MilkTeaAlliance, such as #MilkTeaIsThickerThanBlood, to imply the transnational bond of Milk Tea Alliance members. #WhatsHappeningIn[XCountry] updates people about specific local events. Alliance members also tend to use hashtags that include the country and date in it, to inform users of daily activities and updates.

Sharing practices differ between the platforms. For example, Facebook pages primarily share memes, while Twitter accounts retweet updates on news and information from countries within the Milk Tea Alliance.

- 1 Shui-Yin Sharon Yam, “From Thailand to Belarus, Hong Kong’s spirit of resistance is nurturing grassroots protests elsewhere,” Hong Kong Free Press, October 22, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/BWR4-JWUX

- 2Nnevvy, “Milk Tea Alliance Volunteer ,” Facebook, May 17 2020, https://perma.cc/SZB9-9F4Y.

Figure 11: A post by Twitter user @JiPaTaBook informing Milk Tea Alliance supporters on how to leverage hashtags to spread information. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/8K5T-NBDF. Credit: Screenshot by TaSC.

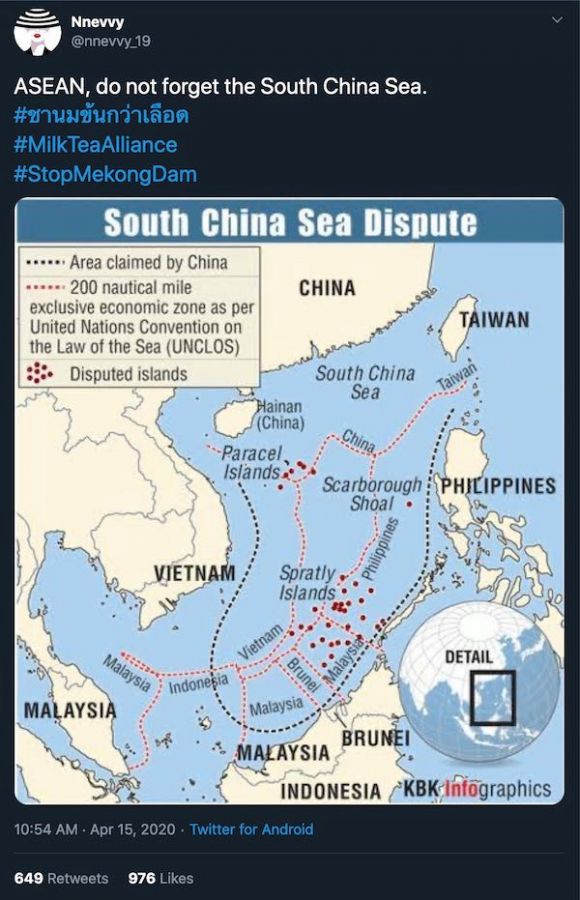

Using the momentum of the meme war between Nnevvy fans and CCP supporters, the newly formed Milk Tea Alliance seized this opportunity of virality to create further mass agitation against authoritarianism and the CCP.1 On April 16, 2020, one day after the Milk Tea Alliance hashtag first trended in Thailand, the administrators of the Nnevvy Facebook page mobilized followers. Their target: China's damming of the Lancang tributary (referred to by the Milk Tea Alliance as the Mekong Dam), the Chinese government’s upstream damming of the Mekong River.2 The dam, which is one of 11 hydropower dams on the Mekong River that China has completed since 1995, has aggravated ecological imbalances, reduced household fishing hauls, and jeopardized a critical food source for 60 million people across Southeast Asia.3 The river, which begins in China, also runs through Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The Nnevvy Facebook page administrators shared a petition calling on the White House administration to take action4 called #StopMekongDam. It asked for 100,000 signatures and provided links to information on why the project needed to be stopped, such as a January 2020 DW Asia video explaining the state of the Mekong Dam.5 The link to the video featured a call to action: “Dear Taiwanese and Hong Kongers now is the time for us to repay the kindness to Thailand. I strongly urge all countries including all south east / Asia and countries around the globe to participate in this petition!”6

- 1 Jackson, Sarah J., Moya Bailey, and Brooke Foucault Welles, “Digitally Dismantling Asian Authoritarianism: Activist Reflections from the #MilkTeaAlliance,” The Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Protest (2020), archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/W6SL-F3DR

- 2 Jill Li and Adrianna Zhang, “#MilkTeaAlliance Brews Pan-Asian Solidarity for Democratic Activists,” VOA News, August 28, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/3HG2-QGVK

- 3Kay Johnson, “Chinese dams held back Mekong waters during drought, study finds,” Reuters, April 13, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/U643-L39F

- 4 T.D, “Stop China to build dam on the upstream Mekong River,” April 16, 2020, archived on web.archive.org, https://web.archive.org/web/20201109040658/https://petitions.whitehouse…

- 5DW News, “Are dams killing the Mekong river? | DW News,” , January 18, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/75PZ-EM4P; https://www.facebook.com/page/107529564254130/search/?q=mekong%20river

- 6 Nnevvy, “” Facebook, May 14 2020, https://perma.cc/Q5MP-QT5E https://www.facebook.com/page/107529564254130/search/?q=petition

Figure 12: Twitter user @akaellenchang using the #StopMekongDam hashtag alongside #MilkTeaAlliance. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/NA2L-XPWH. Credit: Screenshot by TaSC.

A few days later, on April 22, 2020, the Nnevvy Facebook page began using the hashtag #StopMekongDam1 alongside the #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag – a tactic called gaming the algorithm. Since then, many of the top tweets for #MilkTeaAlliance include the hashtag #StopMekongDam. On the last day before the petition reached its deadline for 100,000 signatures, May 22, 2020, the administrators of the Nnevvy Facebook page posted that they needed 30,000 more signatures to reach their goal, urging their followers to sign.2 Two days later, the administrator posted that they had received 21,000 signatures. Ultimately the petition amassed 93,892 signatures in total, just shy of its 100,000 goal.

The TaSC team cannot verify whether the White House received this petition, but it did not receive recognition from the Trump administration. Nevertheless, the petition is an example of the reach and mobilization of the Milk Tea Alliance network.3

While the petition failed to meet its goal, it did not stop other members within the alliance from re-using the hashtag and tactic. While the #StopMekongDam petition campaign was in progress, the Nnevvy Facebook page again employed #MilkTeaAlliance to mobilize its 98,000 followers against alleged CCP involvement in South Korea’s presidential elections. On May 6, 2020, the Nnevvy Facebook page urged its followers to sign a petition that called on the US Congress to act upon the reportedly rigged presidential elections in South Korea.4 This post received 415 comments – many of which were screenshots of Milk Tea Alliance members supporting the petition – and 661 shares. Most of Nnevvy’s posts receive less than 100 comments or shares. Five days later, the page posted that the petition had received over 100,970 signatures, surpassing the petition’s 100,000 signature goal.5

- 1Nnevvy “#nnevvy #StopMekongDam #MilkTeaAlliance” Facebook, April 21 2020, https://perma.cc/Z9HL-EG57

- 2Nnevvy, “Dear Milk Tea Alliance” Facebook, May 14 2020, https://perma.cc/Q5MP-QT5E

- 3Nnevvy “#9K To GO !!! #StopMekongDam” Facebook, May 16 2020, https://perma.cc/KS29-B2NP

- 4Nnevvy “Dear Milk Tea Alliance Korea need our help!” Facebook, May 6 2020, https://perma.cc/XJQ3-946W

- 5Nnevvy “#9K To GO !!! #StopMekongDam” Facebook, May 16 2020, https://perma.cc/KS29-B2NP

Figure 13: Twitter user @nnevvy_19 uses #StopMekongDam alongside their post about the #MilkTeaAlliance. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/4PKD-6VWM. Credit: Screenshot by TaSC.

Stage 3: Responses by industry, activists, politicians, and journalists

As the #MilkTeaAlliance gained momentum on social media through the encouragement of page administrators and of participants of this new, loosely formed group, politicians were quick to comment on the online activism. The #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag garnered significant media attention, political adoption, civil society response, and recognition by politicians – including members of the Chinese Communist Party.

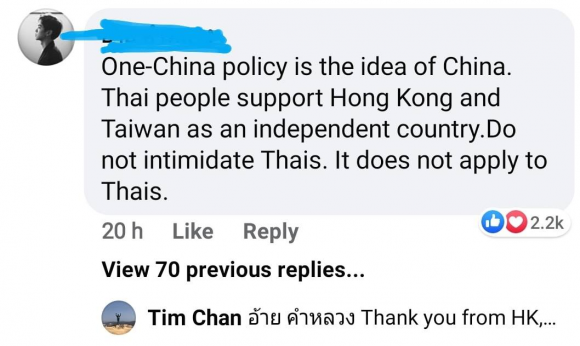

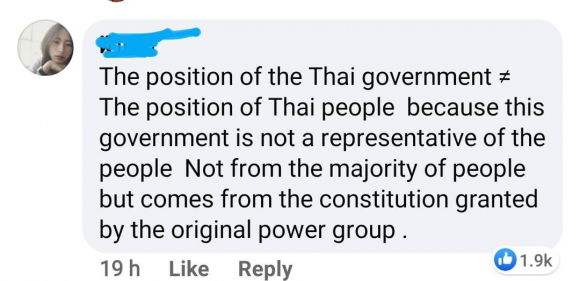

The first official Chinese government recognition of the Milk Tea Alliance came on April 14, 2020. That day, the Chinese Embassy in Thailand – where the Alliance first emerged one day earlier – posted a statement on Facebook: “The recent online noises only reflect bias and ignorance of its maker, which does not in any way represent the standing stance of the Thai government nor the mainstream public opinion of the Thai People.”1 The post received nearly 20,000 comments (most posts there receive less than 50 comments), many of which rejected the embassy’s statement and reaffirmed the Thai people’s commitment to the #MilkTeaAlliance.2

- 1Chinese Embassy Bangkok สถานเอกอัครราชทูตสาธารณรัฐประชาชนจีนประจำประเทศไทย “使馆发言人就近期网上涉华言论发表谈话” Facebook, April 14 2020, https://perma.cc/LCK2-3N8H

- 2Nnevvy, “Many fans informed me regarding of yesterday Chinese Embassy Bangkok announcement of supporting the one wumao country policy” Facebook, April 15 2020, https://perma.cc/VYH8-79TQ

Figure 14: A Facebook user comments on the Chinese Embassy in Thailand’s post on the Milk Tea Alliance. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/VYH8-79TQ. Credit: Screenshot by TaSC.

Figure 15: Another Facebook user comments on the Chinese Embassy in Thailand’s post on the Milk Tea Alliance. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/VYH8-79TQ. Credit: Screenshot by TaSC.

around the world reported on the Milk Tea Alliance, from its meme war origins to its impact on geopolitics in Asia. Headlines such as “How the Milk Tea Alliance became an Anti-China symbol” from The Atlantic1 and “How the Milk Tea Alliance is Remaking Myanmar” by The Diplomat2 show the welcome reception and amplification the Alliance has received from primarily Western press.

The Diplomat article, published in September 2021, contended that this online Alliance rivaled established organizations such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in its influence in Southeast Asia.3 Time, Reuters,4 Bloomberg, and NBC News have all written articles during the days, months, and year since its inception. These mainly explain what the Milk Tea Alliance is, given its leaderless structure, sudden creation, and massive number of followers. Many other outlets, including the South China Morning Post, BBC, Hong Kong Free Press, Al-Jazeera, France 24, Foreign Policy, and Axios have also covered the Milk Tea Alliance.5

Beyond media exposure and a reaction from its political targets, the Milk Tea Alliance also garnered attention from other activists and organizations. On Twitter, a leading Hong Kong pro-democracy activist, Joshua Wong, tweeted his support of the Alliance on May 4, 2020, suggesting that the “#MilkTeaAlliance could create a ‘pan-Asia’ grassroots movement that would draw more attention to social causes in Asia...perhaps we can build a new kind of pan-Asian solidarity that opposes all forms of authoritarianism.”6

Almost one year after the inception of the Milk Tea Alliance, on Feb. 21 2021, the decentralized international hacktivist group Anonymous (@YourAnonCentral), posted to its 5.6 million followers on Twitter that “Anonymous supports the #MilkTeaAlliance with #OpCCP. #WhatsHappeningInMyanmar #WhatsHappeningInThailand #WhatsHappeningInHongKong #WhatsHappeningInIndia #WhatsHappeningInTaiwan #WhatsHappeningInIndonesia.”7 The post received 25,100 retweets, 3300 quote tweets, and 32,300 likes (most of @YourAnonCentral’s tweets receive fewer than 1,000 likes or retweets).

Twitter itself has also recognized and endorsed the Milk Tea Alliance. In April 2021, one year after the Milk Tea Alliance first emerged, the social media platform launched a new emoji: a white cup with a straw in it, set against a backdrop of three different colors (Figure 16). Now, when a tweet mentions the Milk Tea Alliance in English, Thai, Burmese, and Chinese (both simplified and traditional characters), the emoji is automatically added.8 The colors represent the three shades of milk tea – in reference to the milk teas found in the three founding regions of the Milk Tea Alliance – Thailand, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.9 This is not unique – in 2016 Twitter created a Black Lives Matter emoji that appears at the end of the hashtag #blacklivesmatter – but it is a rare show of support from the social media company.

One day after this announcement, #MilkTeaAlliance once again hit trending status in Thailand.10

- 1 Timothy McLaughlin “How Milk Tea Became an Anti-China Symbol,” The Atlantic, October 13 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7LC8-6Q8N

- 2 Jasmine Chia and Scott Singer, “How the Milk Tea Alliance Is Remaking Myanmar,” The Diplomat, July 23, 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/ZH9Z-TLV3

- 3 Ibid.

- 4Patpicha Tanakasempipat, “Young Thais join 'Milk Tea Alliance' in online backlash that angers Beijing,” Reuters, April 15, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/J7HA-TAPG

- 5Wolfram Schaffar and Praphakorn Wongratanawin “The #MilkTeaAlliance: A New Transnational Pro-Democracy Movement Against Chinese-Centered Globalization?” Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 14 (1), 5-35. Archived on Perma.cc, perma.cc/DK5K-4SC8

- 6 Joshua Wong 黃之鋒 (@joshuawongcf) “4/ The alliance represented not only widespread anger over China’s stance on Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang and Tibet, but also wider regional issues linked to growing Chinese influence and expansion through its Belt and Road initiative and infrastructure development, he added,” Twitter, May 4, 2020 archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/M23U-NUDT

- 7 Anonymous (@YourAnonCentral) “Anonymous supports the #MilkTeaAlliance with #OpCCP. #WhatsHappeningInMyanmar #WhatsHappeningInThailand #WhatsHappeningInHongKong #WhatsHappeningInIndia #WhatsHappeningInTaiwan #WhatsHappeningInIndonesia,” Twitter, February 25 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/H4A6-PU4S?type=image

- 8Maerzli ผู้รู้ ผู้ตื่น ผู้กด snooze แล้วนอนต่อ(@_Maerz_) “In milk tea we trust. #MilkTeaAlliance #ชานมข้นกว่าเลือด” Twitter, April 14 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/U7JF-RZXT

- 9“Milk Tea Alliance: Twitter creates emoji for pro-democracy activists,” BBC News, April 8 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/3Z2B-GYW2

- 10“#milkteaalliance in Thailand,” GetDayTrends, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/C3H6-K7Z7

Figure 16: Twitter’s Public Policy account @Policy tweets about the release of the Milk Tea Alliance emoji. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/R77P-G7S2. Credit: Screenshot by TaSC.

Figure 17: The Milk Tea Alliance emoji on Twitter. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/NPG4-9D3L. Credit: Yahoo! News.

Stage 4:

While the CCP recognized and subsequently dismissed the Alliance, the Chinese government made little to no effort to prevent the Milk Tea Alliance from expanding and spreading on Facebook and Twitter, or to mitigate its effects on those platforms. There was, in other words, no mitigation or unclear mitigation in this case. The two U.S.-based platforms are already blocked in China, meaning the government did not need to take further action against the company.

The Chinese government did, however, occasionally try to diminish the movement through critical official statements, but there is little evidence there was any deliberate or coordinated effort to suppress the campaign. In addition to the April 2020 statement by the Chinese embassy in Thailand, China’s foreign ministry dismissed the coalition as a “conspiracy” at a press conference in August 2020. “People who are pro-Hong Kong independence or pro-Taiwan independence often collude online, this is nothing new,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian told Reuters.1 Their conspiracy will never succeed.”

Stage 5: Adjustments by manipulators to the new environment

Unmitigated and increasingly international in its reach, the #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag continues to emerge as a mode of rallying and recruiting supporters on social media during times of regional geopolitical tension or localized conflict. It has continuously been adapted and redeployed across multiple awareness-raising and action-based campaigns.

Fueling offline movements

2020 Hong Kong Protests

A few months after its inception, the #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag trended on Twitter in June 2020, when Beijing passed the controversial Hong Kong National Security Law. The law, which has created a chilling effect on free speech and the island’s movement for autonomy,2 criminalizes activities that the CCP see as “subversion”, “secession”, and “terrorism.” It also allows some people arrested in Hong Kong to be tried in Mainland China. The security law has been used against pro-democracy political candidates in Hong Kong and has been denounced by not only pro-democracy activists there but also Amnesty International,3 Human Rights Watch,4 and Freedom House.5

2020 Thai protests

On July 18, 2020, the #MilkTeaAlliance found a new use in Thailand, where it originally began. University students in Bangkok resumed demonstrations that had been delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020, demanding “the dissolution of the government, a new constitution, and the end of threats to citizens.”6 Two Thai graduate students in Bangkok organized a sister protest with approximately thirty Thai and Taiwanese demonstrators in front of the Thai embassy in Taipei in solidarity with students in Bangkok on Aug. 2, 2020. One week from this initial demonstration, the Taiwan Alliance for Thai Democracy (TATD) was created.7

On Aug. 16, the TATD organized a second protest at the Taipei Main Station, mobilizing hundreds of demonstrators. To promote attendance and spread awareness of the protest, the TATD used the Thai-language hashtag #ไทเปจะไมท่ น(#TaipeiHasHadEnough) and #MilkTeaAlliance on both its Facebook page (@tatdnow) and on Twitter. International and domestic media coverage of the protest included discussions of the hashtags that were propelling attendance.8

For example, on Aug. 18, 2020, Reuters reported on the TATD. In that story, Thai student named Akrawat Siripattanachok said that “[these demonstrations] the first physical expression of the #MilkTeaAlliance.”9 Thai scholar Pavin Chachavalpongpun told The Guardian that the Milk Tea Alliance “effectively shifted online debates concerning critical hurdles against democratization toward street activism and political movements, led by the voices of young netizens.” He highlighted the international influence of the online alliance by pointing out that pro-democracy demonstrators as far as Belarus have been inspired by the Milk Tea Alliance in “their fight against the government of Alexander Lukashenko.”10

Moreover, the Milk Tea Alliance had become an international pipeline for sharing tactics online that members could use at home in their offline protests for democracy. Tips shared through the Milk Tea Alliance, primarily from Hong Kong-based members, ranged from ways to stay safe from police on the barricades to how to extinguish police tear-gas canisters. Thai demonstrators in the country’s 2020 wave of pro-democracy student protests and Myanmar’s anti-coup demonstrators both adopted Hong Kong’s “be water” tactic: they conducted quick and fluid protests that disassembled before police could coordinate proper action. They also had “frontliners” – volunteers who choose to be closest to police so that others could escape to safety if clashes broke out.11

- 1Patpicha Tanakasempipat and Yanni Chow “Pro-democracy Milk Tea Alliance brews in Asia,” Reuters, August 18 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/ZD2R-NAHM

- 2 “China: New Hong Kong Law a Roadmap for Repression,” Human Rights Watch, July 29 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/8KYJ-6UDEn

- 3 “Hong Kong’s national security law: 10 things you need to know,” Amnesty International, July 17, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/WP3W-PLF4

- 4Angeli Datt, “The Impact of the National Security Law on Media and Internet Freedom in Hong Kong,” Freedom House, October 19 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/RNB3-6FMG

- 5“Dismantling a Free Society: Hong Kong One Year After the War,” Human Rights Watch, June 25 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/CX3Z-TLUB

- 6Edoardo Siani, “Purifying Violence: Buddhist Kingship, Legitimacy, and Crisis in Thailand.” Coup, King, Crisis: A Critical Interregnum in Thailand, (2020) 145–166, https://perma.cc/9R3P-NC5Y

- 7Jackson, Sarah J., Moya Bailey, and Brooke Foucault Welles, “Digitally Dismantling Asian Authoritarianism: Activist Reflections from the #MilkTeaAlliance,” The Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Protest (2020), archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/W6SL-F3DR

- 8 Ibid.

- 9 Patpicha Tanakasempipat and Yanni Chow “Pro-Democracy Milk Tea Alliance Brews in Asia.” Reuters, 18 August. 2020. https://perma.cc/4JNK-ABZ7

- 10Schaffar, Wolfram “‘I Am Not Here for Fun’: The Satirical Facebook Group Royalists Marketplace, Queer TikToking, and the New Democracy Movement in Thailand : An Interview With Pavin Chachavalpongpun”. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies 14 (1):129-38. (2021) https://perma.cc/4ANG-5MHM

- 11Jessie Lau, “Myanmar’s Protest Movement Finds Friends in the Milk Tea Alliance,”h The Diplomat, February 13 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7XV4-KAKR

Figure 18: #StandWithThailand is graffitied onto a wall in Hong Kong. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/WD22-RA3W. Credit: Joshua Wong (@joshuawongcf).

The 2020 protests were the largest in Thailand since 2014, and local protestors found support in their Milk Tea Alliance counterparts who tweeted out to them in solidarity.1 Joshua Wong tweeted pictures of Hong Kong protests in 2019 alongside Thai protests to emphasize their solidarity. He received over 100,000 retweets on the post.2 Nathan Law, a pro-democracy Hong Kong activist and politician, tweeted3 a petition calling for global support for Thai student protests. By May 2022, it had received 24,981 signatures out of its 25,000 signature goal.4 Across Hong Kong, pro-democracy businesses have even hung up and disseminated #MilkTeaAlliance-themed postcards.5

India Celebrates Taiwanese National Day

The #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag re-emerged again when China issued a diktat to Indian publications on how to properly report on Taiwan’s National Day in October 2020.6 In response, the Milk Tea Alliance shared a meme depicting Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-Wen and and India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi toasting each other with milk tea and masala chai (Indian spiced milk tea). It was shared on social media with the hashtags #TweetForTaiwan and #TaiwanIndiaBhaiBhai (which translates to #TaiwanIndiaBrotherBrother).7 Posters congratulating Taiwan on its 109th National Day, celebrated on Oct. 10, 2020, were put up near the Chinese embassy in New Delhi.8

On the same day, Taiwanese Vice President Lai Ching-te tweeted “Proud to see our flag fly high and be recognized all over the world. We thank the people from so many countries who today expressed congratulations and support. Especially our Indian friends. Namaste! #TaiwanNationalDay #JaiHind #MilkTeaAlliance.” The tweet received 42,900 likes, which is his most-liked tweet as of March 2022 (most of Ching-te’s posts receive fewer than 1,000 likes).9 Taiwan’s envoy to the US, Bi-khim Hsiao, also retweeted a video of these posters, writing: “Wow! What a #MilkTeaAlliance” on her personal account.10 This tweet was one of the most popular tweets on her account, receiving 20,000 likes. #TaiwanNationalDay trended on Twitter in India on October 10, as Indians sent Taiwan their well wishes. In turn, one month later on November 14, 2020 during the Hindu festival of Diwali, Joshua Wong tweeted out “#दीपावली_की_हार्दिक_शुभकामनाएं #दीपावली #HappyDiwali to all of our #MilkTeaAlliance friends in India. Hong Kong and India had both faced threats posed by the pandemic and CCP while the friendship between us had been strengthened in this challenging 2020.”11

- 1Joshua Wong 黃之鋒 (@joshuawongcf) “#SaveThaiDemocracy #WhatsHappeningInThailand #RespectThaiDemocracy,” Twitter, August 17th 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/V5GC-H3JQ

- 2Joshua Wong 黃之鋒 (@joshuawongcf) “#MilkTeaAlliance” Twitter, October 17 2020, https://perma.cc/3JQD-Q8GL

- 3Nathan Law 羅冠聰 @nathanlawkc “[Urgent: Petition to #StandWithThailand] คำร้องเพื่อเปลี่ยนแปลง http://chng.it/KVz8msP9Fh We, Hongkongers, have faced endless political persecution in the year-long ongoing protest. The fight for democracy is a collective battle, and we stand with our fellows in #MilkTeaAlliance.” Twitter, October 17 2020, https://perma.cc/3JQD-Q8GL

- 4Sunny Cheung, “Global Petition: Supporting Thai Protesters,” Change.org, https://perma.cc/QN6A-9FMT

- 5Jackson, Sarah J., Moya Bailey, and Brooke Foucault Welles, “Digitally Dismantling Asian Authoritarianism: Activist Reflections from the #MilkTeaAlliance,” The Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Protest (2020), archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/W6SL-F3DR

- 6Eric Chang, “China instructs Indian media how to report on Taiwan’s National Day,” Taiwan News, October 8 2020, https://perma.cc/42X9-ZRF7

- 7The Diplomat, October 20 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/T6MV-8F3J

- 8Jassie Hsi Cheng “The Taiwan–India ‘Milk Tea Alliance,” The Diplomat, October 20, 2020, https://perma.cc/J39J-JA4U

- 9賴清德Lai Ching-te (@ChingteLai) “Proud to see our flag fly high and be recognized all over the world. We thank the people from so many countries who today expressed congratulations and support. Especially our Indian friends. Namaste! #TaiwanNationalDay #JaiHind #MilkTeaAlliance,” Twitter, Oct 9 2020, https://perma.cc/N7KC-3ZHC

- 10 Bi-khim Hsiao 蕭美琴 (@bikhim) “Wow! What a #MilkTeaAlliance” Twitter, October 9 2020, https://perma.cc/9B7K-XGF6

- 11 Joshua Wong 黃之鋒 (@joshuawongcf) “#दीपावली_की_हार्दिक_शुभकामनाएं #दीपावली #HappyDiwali to all of our #MilkTeaAlliance friends in India. Hong Kong and India had both faced threats posed by the pandemic and CCP while the friendship between us had been strengthened in this challenging 2020.” Twitter, November 14 2020, https://perma.cc/6WDS-PX2N

Figure 19: A meme circulating on Twitter during October 2020 depicts the milk teas of India, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Taiwan, signifying India’s inclusion into the alliance. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/4ZH2-92P8. Source: Twitter user @PingloveTaiwan.

Figure 20: A meme depicting Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi cheersing Indian milk tea with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, who holds Taiwanese bubble tea. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/4ZH2-92P8. Source: Twitter user @PingloveTaiwan.

US Republican Party

While the initial Milk Tea Alliance campaign was primarily used by Southeast Asians, the anti-CCP rhetoric of the Milk Tea Alliance often dovetailed with that of the U.S. Republican Party, This has lead to support from perhaps unlikely corners.

A petition to the White House circulated by members of the Milk Tea Alliance in April 2020 from Hong Kong called for reparations on behalf of Hong Kongers “for loss due to Chinese Virus.” Smaller and accounts have tweeted the #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag alongside #ChineseVirus and #ChinaVirus, echoing terms that were popularized by Pres. Donald Trump in 2020 to incite and spread blame for the COVID-19 pandemic on the Chinese people.1 The #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag can be found accompanying tweets of other Republican accounts, such as @SolomonYue, the CEO of Republican Overseas lobbying group. He refers to COVID-19 as the "Wuhan Coronavirus."2 Other individual Twitter accounts used the #MilkTeaAlliance and #WuhanCoronavirus to wish Trump a get well soon when he contracted COVID-19 in October 2020.3 The Nnevvy Facebook page is one of the first and largest Milk Tea Alliance pages to allude to COVID-19 in the same way that American right-wing leaders do. These sentiments of aligning with U.S. Republican Party views can also be found within factions of the Asian pro-democracy movement that are sympathetic to Trump.4

Re-emergence During Political Upheaval

2021 Myanmar Coup

Almost a year out from its birth, the Milk Tea Alliance once again activated its network – which had long included pro-democracy youth in Myanmar – in February 2021 to oppose a military junta that had overthrown Myanmar's elected government. To signify Myanmar's official incorporation into the Alliance, Thai artist Sina Wiyyayawiroj created an online graphic including Myanmar, which was then posted on Milk Tea Alliance online hubs such as the Nnevvy Facebook page (Figure 21).5

Two weeks after the Myanmar military coup, on Feb. 14, 2021, Hong Kong's Nathan Law encouraged his Twitter followers to support the resistance movement in Myanmar. “Friends from #MilkTeaAlliance and democratic countries, I think all of you should be concerned with the latest developments in #Myanmar: Mass military presence, firing at citizens, internet cutoff… A potential massacre is happening. Let's keep tweeting and supporting them.”6

- 1St (@stsk1v3) “Food Culture in the World #MilkTeaAlliance #nmslese #ChineseVirus” Twitter, April 28 2020, https://perma.cc/F8F3-CATY

- 2CatZ (@Z_princcess) “One world one fight! Say NO to communist China! #CCPVirus #ChinaLiedAndPeopleDied #ChineseVirus #Chinazi #MilkTeaAlliance,” Twitter, May 12 2020, https://perma.cc/9ULB-RUEP

- 3“#wuhancoronavirus #milkteaalliance” Twitter, https://perma.cc/9SLF-TWAP?type=image

- 4 Mary Hui “Hong Kong’s democracy activists see kindred spirits in the US Capitol insurrection” Quartz, January 20 2021, https://perma.cc/H9UC-BUTA; Helen Davidson “Why are some Hong Kong democracy activists supporting Trump’s bid to cling to power?” The Guardian, November 12 2020, https://perma.cc/ZTU4-D7VC

- 5Vijitra Duangdee “Asia’s #MilkTeaAlliance has a new target brewing – the generals behind the Myanmar coup,” SCMP February 4 2021, https://perma.cc/5WWW-34WW

- 6Nathan Law 羅冠聰 (@nathanlawkc) “Friends from #MilkTeaAlliance and democratic countries, I think all of you should be concerned with the latest developments in #Myanmar: Mass military presence, firing at citizens, internet cutoff… A potential massacre is happening. Let's keep tweeting and supporting them.” Twitter, February 14 2021, https://perma.cc/GA8T-WKPZ

Figure 21: A poster of the Milk Tea Alliance featuring milk tea from Taiwan, Thailand, Hong Kong, India, and Myanmar. By artist Sina Wittayaqiroj. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/R27C-NDGT. Source: South China Morning Post

Figure 22: Demonstrators in Myanmar bring Milk Tea Alliance posters to their protest. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/3Z2B-GYW2. Source: Jack Taylor/AFP

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine

Elsewhere, the Milk Tea Alliance has used its networks to raise awareness of issues outside Asia, though with varying levels of intensity, efficacy, and coordination.

Most recently, on Feb. 26, 2022, the Nnevvy Facebook page tweeted a photo of the Ukrainian flag overlaid with the text “Stand with Ukraine'' – the account’s first post since September 2021. Other participants in the Milk Tea Alliance have taken an interest in Ukraine, too. Three days after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Twitter page @AllianceMilkTea on Feb. 27 retweeted a thread in support of Ukrainian refugees by the Hong Kong activist @lausanhk. This was @AllianceMilkTea’s first post on Ukraine. The next day, the account published a thread “on solidarity with Ukraine across the #MilkTeaAlliance,”1 and retweeted photographs of pro-Ukraine protests held in Hong Kong, Myanmar, Taiwan, Malaysia, Belarus, China, and Thailand. Uhgyur refugees around the world also gathered to show their support for Ukraine, and photos of their February 2022 mobilizations were shared in Milk Tea Alliance circles (see Figure 23 below).

- 1#MilkTeaAllianceBrew (@AllianceMilkTea) “Hong Kongers in Netherlands! Talk about transnational solidarity,” Twitter, February 28 2022, https://perma.cc/ACL6-LAA8?type=image

Figure 23: A protest in Myanmar against the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/ZC7F-KTQE. Source: Civil Disobedience Movement (@cvdom2021) on Twitter.

Many @AllianceMilkTea posts regarding the Russian invasion in Ukraine are critical of Western media’s vigorous response to that war, contrasting it with the same outlets’ negative or absent coverage of many conflicts in the Global South. The account has also highlighted the involvement of Russia in areas more directly related to the original Milk Tea Alliance, such as Russia’s supply of military arms to the Myanmar military.1

Conclusion

The Milk Tea Alliance is an example of how an online meme war can both transcend borders and jump the online-offline divide, provoking reactions from governments, activists, and academics worldwide. The case also demonstrates how online campaigns for democracy can be adapted and redeployed in other countries where people are organizing to struggle against illiberal governments. What started as a Thai-led counter-campaign against pro-CCP Twitter accounts became an international activist network that captured youth frustration against their own governments and with the growing influence of China in the region.

Although many of the participants in the Milk Tea Alliance are operating under severe constraints in their own countries, the network itself has provided support and a means of mobilization.

“The young people know that their political capital is weak because they don’t have money, and not many of them have political connections. But they have found support and political resonance online,” Veronica Mak, a sociology professor at Hong Kong Shue Yan University, told Time magazine in October 2020. Joshua Wong echoed these sentiments in a thread on Twitter, quoting from an interview he had done about the Milk Tea Alliance for the Telegraph.2 “Milk Tea Alliance is more about how netizens and key opinion leaders on social media can take a leadership role and generate pressure against the momentum of Beijing’s machine,” he said.3

However, as repression increases in the places where the Milk Tea Alliance emerged, from Thailand to Myanmar, it remains to be seen whether this network can continue to fuel political engagement that translates into real world change.

As the coalition grows, so do its politics, motivations, and objectives.

Twitter user @XunlingAu, who identifies as a part of the Milk Tea Alliance, wrote on April 9, 2021: “Too many ‘articles’ on the #MilkTeaAlliance treat it as a monolithic organisation instead of a fluid, loose coalition of diff[e]rent movements/causes. Each movement contained is also not monolithic. It is sp[r]awling & has contradictions. There isn't a single source that covers it all.”4 Later in the thread, a post explains that, “We have to recognise that in all the diversity there will be contradictions, problems, challenges, bad faith actors but this shouldn't detract from the fact that as a vehicle to raise up the voices of the oppressed the #MilkTeaAlliance does that very well.”5

@XunlingAu touches upon the problems that reporters, researchers and those even within the Alliance have faced in defining and explaining the objectives and intentions of this massive, leaderless and structureless online alliance. As noted in Stage 5, the movement encompasses actors from both the left and right on the political spectrum. Sometimes, they share content that may be deemed racist or at odds with the network’s original values and objectives. That said, although the alliance consists of diverse actors within various geopolitical contexts and different goals, the solidarity that fuels the alliance is rooted in a common contempt for authoritarianism in general and for the CCP in particular.

- 1Niao Collective (@NiaoCollective) “ASEAN, showing us all once again that they are clowns,” Twitter, May 28 2022, https://perma.cc/AKX3-QGL5; #MilkTeaAlliance Brew( @AllianceMilkTea) “Quick sanctions all over the world against Russia's invasion of Ukraine shows how the lack of response towards Myanmar's military violence, is simply because countries are profitting from it,” Twitter, March 1 2022, https://perma.cc/64GN-UCC3; Justice For Myanmar (@JusticeMyanmar) “#Russia and #China are aiding and abetting the #Myanmar military's international crimes through arms sales and tech transfer. The international community must act to stop the flow of arms to #MyanmarMilitaryTerrorists. We demand a #GlobalArmsEmbargo now!” Twitter, March 5 2022, https://perma.cc/YW4Y-Q8FS

- 2Nicola Smith “#MilkTeaAlliance: New Asian youth movement battles Chinese ,” Telegraph, May 3 2020, https://perma.cc/K5SW-GQNU

- 3 Joshua Wong 黃之鋒 (@joshuawongcf) “3/ “Milk Tea Alliance is more about how netizens and key opinion leaders on social media can take a leadership role and generate pressure against the momentum of Beijing’s propaganda machine,” he said” Twitter, May 4 2020, https://perma.cc/9PSR-DPQQ?type=image

- 4 Xun-ling Au 歐迅灵 (@XunlingAu) “Too many "articles" on the #MilkTeaAlliance treat it as a monolithic organisation instead of a fluid, loose coalition of diffrent movements/causes. Each movement contained is also not monolithic. It is spawling & has contradictions. There isn't a single source that covers it all,” Twitter, April 9 2021, https://perma.cc/6NUG-W7J7?type=image

- 5 Xun-ling Au 歐迅灵 (@XunlingAu) “Even this amazing work (Defo go read it) doesn't capture it all. It is a 36 page peer reviewed paper by @taiwanadam & Autumn Lai on the #MilkTeaAlliance and this is the work of months not days but the MTA morphs and changes rapidly,” Twitter, April 9 2021, https://perma.cc/M7C2-VYHF?type=image

Cite this case study

Jazilah Salam, "Milk Tea Alliance: From Meme War to Transnational Activism," The Media Manipulation Case Book, March 7, 2023, https://casebook-static.pages.dev/case-studies/milk-tea-alliance-meme-war-transnational-activism.