Trading Up the Chain: The Hydroxychloroquine Rumor

Overview

In early 2020 as the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) took hold and turned from epidemic to pandemic, global information ecosystems became overwhelmed in what the World Health Organization called an infodemic, “an overabundance of information — some accurate and some not — that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it.”1 In times of crisis, when local, timely, and relevant information is sorely needed, medical misinformation thrives.

This case study focuses on one such rumor: that the antimalarial medications chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) were effective treatments for COVID-19. Beginning as cloaked science published as a document, the rumor quickly traded up the chain to President Trump and his administration, who amplified it and muddied the waters around COVID-19. This rumor ultimately led to a run on the medications, imperiling people who rely on them to treat existing ailments,2 and to at least one person’s death, after a man ingested chloroquine phosphate — aquarium cleaner — believing it to be the chloroquine he had heard Trump tout as a treatment.3

- 1 “1st WHO Infodemiology Conference,” World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2020/06/30/default-calendar/1st-who-infodemiology-conference.

- 2Maya Harris, “Some Patients Really Need the Drug That Trump Keeps Pushing,” The Atlantic, April 4, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/save-hydroxychloroquine-people-like-me/609865/.

- 3 “Coronavirus: Man dies taking fish tank cleaner as virus drug,” BB News, March 24, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/52012242.

STAGE 1: Manipulation Campaign Planning and Origins

In mid-March 2020, as measures aimed at containing COVID-19 were rolled out across the globe, unproven ideas about SARS-CoV-2 antidotes began to circulate. From among this mix of rumors, misinformation, and cutting-edge science emerged a dominant unproven idea: that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine — two anti-malarial drugs — could treat COVID-19.1 Scientists responded to these claims by quickly researching the medicine’s impact on COVID-19. Many early HCQ studies were anecdotal2 and mixed in their results.3 But by the end of 2020, as more studies were published, it became evident that HCQ was not an effective treatment.4 For example, a National Institutes of Health study published in November 2020 evaluating the safety and effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of adults with COVID-19 formally concluded that the drug provides no clinical benefit to hospitalized patients. At time of writing, the CDC and WHO have repeated the finding that HCQ does not reduce the death rate of hospitalized COVID-19 patients.5

However, in the early months of the pandemic, before there was scientific consensus, politicians, , online , and internet users alike recommended this course of treatment, seeding the rumor that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine could prevent and treat COVID-19 across the internet. The rumors had enough early engagement that Dr. Janet Diaz, the lead for clinical case management in the World Health Organization (WHO) Health Emergencies program, had to issue a statement that there was “no proof” that chloroquine was a coronavirus cure.6 But the speculation of HCQ’s therapeutic and preventive potential continued. A March 10, 2020 Science News story, for example, titled “Repurposed drugs may help scientists fight the new coronavirus” included chloroquine among its list of potential treatments.7

Although there were concurrent and separate studies and online conversations promoting HCQ, this case focuses on one specific campaign to spread the HCQ misinformation: a March 13, 2020 Google document titled “An Effective Treatment for Coronavirus (COVID-19),” by James Todaro and Gregory Rigano, two individuals who lobbied for HCQ as a treatment for COVID-19.8 Their Google document muddied the waters about the uses of the drugs and the public health response to the active crisis of the pandemic, and is an example of how open collaboration tools can be exploited to spread misinformation.

Their Google document is an example of — the use of scientific jargon and community norms to cloak or hide a political, ideological, or financial agenda within the appearance of legitimate scientific research. Although Todaro received his medical degree from Columbia University in 2014, he no longer practices ophthalmology. He has been “involved with” bitcoin technology since 2013,9 and is the CEO of MedX Protocol and Managing Partner of Blocktown Capital.10 Rigano, the other named author, is “a Long Island attorney and blockchain enthusiast . . . [who] was falsely presenting himself as an adviser to Stanford Medical School” in the Google doc, according to The New York Times Magazine.11

The Google document, which uses technical language and multiple graphs, cited guidance from South Korea12 and China13 on using chloroquine as an effective antiviral treatment against COVID-19. The Google document does not present original research. It instead summarizes other studies on chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. Included in Todaro and Rigano’s source list are articles from 2003, 2008, 2016, and 2019 about antimalarial drugs as treatments for viruses. The only citation that focuses on COVID-19 was from Dr. Didier Raoult, who on March 4, 2020 published an article entitled, “Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19,” which argued for their use in COVID-19 treatment.14

Todaro and Rigaro claimed their Google document was written “in consultation with Stanford University School of Medicine, UAB School of Medicine and National Academy of Sciences researchers.”15 Those parties denied these claims.

An excerpt of the Google document reads:

Use of chloroquine (tablets) is showing favorable outcomes in humans infected with Coronavirus including faster time to recovery and shorter hospital stay. US CDC research shows that chloroquine also has strong potential as a prophylactic (preventative) measure against coronavirus in the lab, while we wait for a vaccine to be developed.16

These sentences drove home the compelling idea that there was an existing drug that could both cure and prevent coronavirus. That false promise became a partisan issue when it was politically adopted and pushed by Trump, Fox News, and “Reopen” groups on social media that the economy must be reopened — and could be safely.17

The question of when to reopen the economy became a contentious wedge issue that pitted Trump’s team — and their economic priorities — against science, which promoted social distancing. As Politico reported, the divide between the Trump administration and public health “highlights widening tensions in the Trump administration between protecting the American public against the spread of the coronavirus and reopening the economy as soon as possible.”18

The HCQ Google document gave ammunition to those arguing that the economy should be reopened. It ended with a call for distributed amplification: readers should send it to their networks, translate it into other languages, and spread the word that hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine could treat COVID-19.

- 1 Hydroxychloroquine is also sold under the brand name Plaquenil.

- 2 Umair Irfan, “The Evidence for Using Hydroxychloroquine to Treat Covid-19 Is Flimsy,” Vox, April 7, 2020, https://www.vox.com/2020/4/7/21209539/coronavirus-hydroxychloroquine-covid-19-clinical-trial.

- 3 Katie Thomas and Knvul Sheikh, “Small Chloroquine Study Halted Over Risk of Fatal Heart Complications,” The New York Times, April 13, 2020, sec. Health, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/12/health/chloroquine-coronavirus-trump.html.

- 4 Lara Bull-Otterson et al, “Hydroxychloroquine and Chloroquine Prescribing Patterns by Provider Specialty Following Initial Reports of Potential Benefit for COVID-19 Treatment — United States, January–June 2020,” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69 (2020), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6935a4.htm; April Jorge, “Hydroxychloroquine in the prevention of COVID-19 mortality,” The Lancet Rheumatology, March 4, 2021, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanrhe/article/PIIS2665-9913(20)30390-8/fulltext .

- 5 “Hydroxychloroquine does not benefit adults hospitalized with COVID-19,” National Institutes of Health (NIH), November 9, 2020, https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/hydroxychloroquine-does-not-benefit-adults-hospitalized-covid-19.

- 6 Berkeley Lovelace, Jr., “Early trial results for potential coronavirus treatments expected in 3 weeks, WHO says” CNBC, February 20, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/20/early-trial-results-for-potential-coronavirus-treatments-expected-in-three-weeks-who-says.html.

- 7 Tina Hesman Saey, “Repurposed drugs may help scientists fight the new coronavirus,” Science News, March 10, 2020, https://www.sciencenews.org/article/coronavirus-covid19-repurposed-treatments-drugs.

- 8 James Todaro and Gregory Rigano, “An Effective Treatment for Coronavirus (COVID-19),” Google Docs, March 13, 2020, https://docs.google.com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vTi-g18ftNZUMRAj2SwRPodtscFio7bJ7GdNgbJAGbdfF67WuRJB3ZsidgpidB2eocFHAVjIL-7deJ7/pub.

- 9“James Todaro - Co-Founder, CEO @ Blocktown Capital,” Crunchbase, https://www.crunchbase.com/person/james-todaro.

- 10“James Todaro | People Directory,” CryptoSlate, https://cryptoslate.com/people/james-todaro/.

- 11 Scott Sayare, “He Was a Science Star. Then He Promoted a Questionable Cure for Covid-19.,” The New York Times, May 12, 2020, sec. Magazine, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/12/magazine/didier-raoult-hydroxychloroquine.html.

- 12 Kwak Sung-sun, “Physicians work out treatment guidelines for coronavirus,” KBR, February 13, 2020, http://www.koreabiomed.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=7428.

- 13 Expert consensus on chloroquine phosphate in the treatment of new coronavirus pneumonia, “Expert Consensus on Chloroquine Phosphate in the Treatment of New Coronavirus Pneumonia,” Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Medicine 43, no. 00 (n.d.): E019–E019, https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0019.

- 14 Philippe Colson et al., “Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine as Available Weapons to Fight COVID-19,” International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 55, no. 4 (April 1, 2020): 105932, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932.

- 15 Nick Robins-Early, “The Hucksters Pushing A Coronavirus ‘Cure’ With The Help Of Fox News And Elon Musk,” HuffPost, March 30, 3030, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/chloroquine-coronavirus-rigano-todaro-tucker-carlson_n_5e74da41c5b6eab77946c3b3.

- 16 James Todaro and Gregory Rigano, “An Effective Treatment for Coronavirus (COVID-19).”

- 17 Madeline Peltz and Justin Horowitz, “Pro-Trump Media Tout Hydroxychloroquine as a Treatment for Trump’s Case of Coronavirus,” Media Matters for America, October 5, 2020, https://www.mediamatters.org/coronavirus-covid-19/pro-trump-media-tout-hydroxychloroquine-treatment-trumps-case-coronavirus; Kayla Gogarty, “Trump and His Administration Are Leading the Discussion about Reopening Schools among Right-Leaning Pages,” Media Matters for America, July 17, 2020, https://www.mediamatters.org/facebook/trump-and-his-administration-are-leading-discussion-about-reopening-schools-among-right.

- 18 Dan Diamond and Nancy Cook, “Trump’s ‘Hail Mary’ Drug Push Rattles His Health Team,” Politico, April 6, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/04/06/trump-drug-coronavirus-hydroxychloroquine-170543.

STAGE 2: Seeding Campaign Across Social Platforms and Web

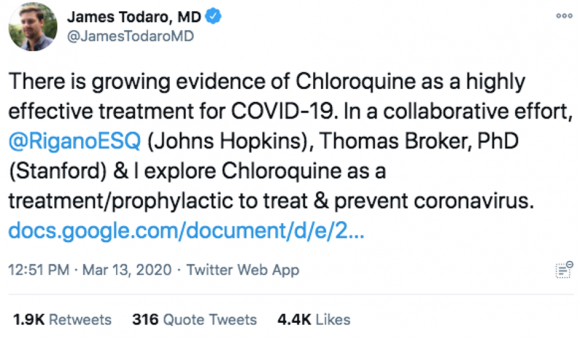

On March 13, James Todaro tweeted a link to the Google document on Twitter (figure 1 below).1 Todaro claimed the information in the Google document was presented in collaboration with researchers from Columbia, Stanford, and Johns Hopkins, whom he named. These details implied academic rigor and lent credibility to the hypothesis. The third author, however, later told ABC that he “had nothing to do with the paper whatsoever,” and asked the authors to remove him from the document.2 His name is no longer listed as an author, but the Google document still references March 12, 2020 phone calls with him.

- 1 James Todaro (@JamesTodaroMD), “There Is Growing Evidence of Chloroquine as a Highly Effective Treatment for COVID-19. In a Collaborative Effort, @RiganoESQ (Johns Hopkins), Thomas Broker, PhD (Stanford) & I Explore Chloroquine as a Treatment/Prophylactic to Treat & Prevent Coronavirus. Https://T.Co/GCgJDxhAjV,” , March 13, 2020, https://twitter.com/JamesTodaroMD/status/1238553266369318914; James Todaro and Gregory Rigano, “An Effective Treatment for Coronavirus (COVID-19).”

- 2 Fergal Gallagher, “Tracking Hydroxychloroquine Misinformation: How an Unproven COVID-19 Treatment Ended up Being Endorsed by Trump,” ABC News, April 22, 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/Health/tracking-hydroxychloroquine-misinformation-unproven-covid-19-treatment-ended/story?id=70074235.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became increasingly common for scientists to publish new results about the virus on open science preprint servers, to get information to the public and the research community quickly; in that environment, Todaro’s Google document appeared akin to those legitimate preprint articles.1 became a vulnerability for media manipulators to exploit.

The tweet received quick attention and was later amplified by celebrities, journalists, and politicians. CrowdTangle analysis suggests that the link to the Google doc received 69,000 Facebook interactions.2

- 1 Joan Donovan and Jennifer Nilsen, “Cloaked Science: The Yan Reports,” Casebook, February 12, 2021, https://mediamanipulation.org/case-studies/cloaked-science-yan-reports.

- 2 Between March 13, 2020 and February 4, 2021.

STAGE 3: Responses by Industry, Activists, Politicians, and Journalists

Three days after Todaro’s initial tweet, Tesla CEO and Twitter provocateur Elon Musk retweeted the study to his 40M followers,1 amplifying the rumor of a “cure” that had been circulated among technology investors. That same day, the document was referenced on Stratechery, a newsletter written by analyst Ben Thompson that is popular among venture capitalists and technology executives with over 26,000 paid subscribers.2

From here, it caught the attention of mainstream media and traded up the chain — eventually all the way to the White House. On March 16, Rigano appeared on Fox News on The Ingraham Angle to promote this study.3 Two days later, conservative , Breitbart and The Blaze, published stories on it.4

The Google document also attracted the attention of French professor, physician, and infectious disease expert Didier Rauolt. After he saw that Todaro’s tweet was gaining traction, he reached out to the co-authors and shared his own hydroxychloroquine data with them.5 He further allowed Todaro to tweet the results of his study (also as a Google document) two days before he published it as a preprint.6 Dr. Rauolt used Todaro and Rigano’s audience to amplify his research, and his name lent early credibility to Todaro and Rigano’s document. (Dr. Rauolt’s paper, which had been peer-reviewed, was later retracted).7

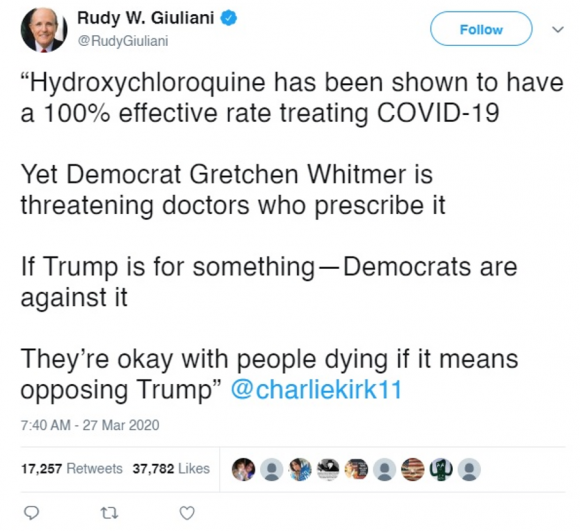

On March 19, the HCQ-as-cure rumor received further amplification when Rigano made two major media appearances: Glenn Beck had Rigano on his radio show,8 and Tucker Carlson hosted Rigano on his primetime Fox TV show. On Tucker Carlson Tonight, Rigano claimed that chloroquine had “a 100% cure rate against coronavirus.”9 This statement — a claim originally made by Dr. Rauolt — was false, but it gained attention from high-profile conservative voices. Rudy Guiliani repeated it in a tweet a week later (attributing the quotation to Charlie Kirk), which was removed by Twitter (figure 2 below).

- 1 Elon Musk (@elonmusk), “Maybe Worth Considering Chloroquine for C19 Https://T.Co/LEYob7Jofr,” Twitter, March 16, 2020, https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1239650597906898947.

- 2 Gallagher, “Tracking Hydroxychloroquine Misinformation;” “Case Study: How One Writer Makes $3.2 Million a Year From a Newsletter,” Medium, November 19, 2020, https://bettermarketing.pub/how-one-writer-makes-3-2-million-a-year-from-a-newsletter-476f011104a9.

- 3 Philip Bump, “The Rise and Fall of Trump’s Obsession with Hydroxychloroquine,” Washington Post, April 24, 2020, sec. Politics, http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/04/24/rise-fall-trumps-obsession-with-hydroxychloroquine/.

- 4Jeff Wise, “How Donald Trump’s Chloroquine Campaign Started,” Vanity Fair, March 24, 2020, https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2020/03/trumps-touting-of-an-untested-coronavirus-drug-is-dangerous.

- 5 Sayare, “He Was a Science Star. Then He Promoted a Questionable Cure for Covid-19.”

- 6Sayare.

- 7 Adam Marcus, “Hydroxychloroquine-COVID-19 Study Did Not Meet Publishing Society’s ‘Expected Standard,’” Retraction Watch, April 6, 2020, https://retractionwatch.com/2020/04/06/hydroxychlorine-covid-19-study-did-not-meet-publishing-societys-expected-standard/; Andrea Voss, “Statement on IJAA Paper,” International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement.

- 8 Glenn Beck, “The Glenn Beck Program - A Glimmer of Hope | Guests: Matt Walsh & Gregory Rigano,” Stitcher, March 19, 2020, https://www.stitcher.com/show/undefined/episode/a-glimmer-of-hope-guests-matt-walsh-gregory-rigano-3-19-20-68152571.

- 9 Jeff Wise, “How Donald Trump’s Chloroquine Campaign Started.

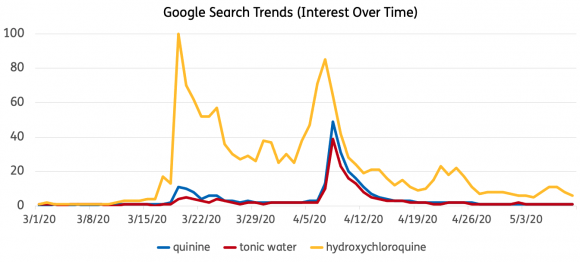

During the interview with Tucker Carlson, Rigano instructed viewers to go to his website, www.covidtrial.io, and his Twitter account for more information. Moments later, online searches for “quinine” and “tonic water” (which contains quinine) surged (figure 3 below), along with other keywords such as “quinine supplement” and “malaria drug for coronavirus.”

Figure 3: Google trends graph of “quinine,” “tonic water,” and “hydroxychloroquine.” On March 19th, the day of the first spike, Trump called the drug “a game changer.” That night, Rigano’s appeared on Tucker Carlson Tonight. The spike around April 8th follows Trump’s April 5th question -- “what do we have to lose?” -- about hydroxychloroquine, the press following his statement, and American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Rhythm Society joint statement about the dangers of hydroxychloroquine (Click image to view full size). Credit: TaSC.

Further, Rigano emphasized the urgency with which he thought Trump should act: “The President has the authority to authorize the use of hydroxychloroquine against coronavirus immediately. He has cut more red tape at the F.D.A. than any other President in history.”1

Smaller outlets also amplified Todaro and Rigano’s claims, contributing to the confusion and further muddying the waters. On March 19, 2020, the same day that Rigano was featured on Tucker Carlson and Glenn Beck, The Tennessee Star, The Ohio Star, The Minnesota Sun, and The Michigan Star all circulated the Google document via online articles published by journalist Jason Reynolds. Though these publications all have the appearance of local news sites, Politico reported that they were actually created by Tea Party-connected conservative activists Michael Patrick Leahy, Steve Gill, and Christina Botteri.2 Despite this partisan mission, the sites advertise themselves as “unbiased,” “local news,” and “most reliable.”3 The viewership of these sites contributed to the spread of Todaro and Rigano’s campaign, where it was disguised as reliable and unbiased information.

On social media, rumor sharing about hydroxychloroquine continued among prominent right-leaning individuals and groups. Charlie Kirk, the founder of Turning Point USA (a conservative non-profit organization), tweeted a video clip of the segment to his two million followers, encouraging, “RT If President @realDonaldTrump should immediately move to make this available.”4 A group of Republican billionaires, Job Creators Network, ran Facebook ads asking for signatures in a petition asking Trump to “CUT RED TAPE,” and making the drug available to COVID-19 patients.5

After Carlson’s segment, Trump, his allies, and those seeking to reopen the country adopted HCQ as a potential treatment for COVID-19. At a White House press briefings on March 19, Trump stated that HCQ had “shown very encouraging – very, very encouraging early results.”6

Fox News figures and guests made 275 claims promoting HCQ and chloroquine between March 23 and April 6.7 Media Matters argues that Fox’s promotion of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine resulted in Trump running with the insufficiently tested hypothesis.8 Senior Research Fellow Matt Gertz tweeted that “Fox is telling him antimalarials could be miracle cures & less disruption to economy needed.”9 Laura Ingraham bragged about her ability to influence Trump's thinking the same day on her show10 — which is backed up by Trump tweets that repeat her specific talking points.11

Beyond media exposure, the promotion of HCQ to the general public resulted in policy and behavioral changes. For example, under the direction of Governor Andrew Cuomo, New York City initiated clinical trials on the effectiveness of HCQ, citing positive results seen by doctors in Africa and elsewhere.12 The also shifted the demand for HCQ, creating a shortage of the drug for individuals suffering from malaria and lupus, conditions for which HCQ is a proven and critical treatment. Non-profit groups and advocates urged people not to deplete the stockpile for those in need.13

On March 28, following President Trump’s remarks, the FDA received an emergency authorization that fast-tracked the use of HCQ sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products to treat COVID-19.14 Discussion about the drug also led to rigorous National Institutes of Health trials on it. Simultaneously, clinical trials were happening internationally.15

Those who spoke out against HCQ, however, risked backlash. On April 22, Rick Bright, the former director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, said that he was demoted because he argued against the Trump administration’s promotion of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine and had been pressured to put funding toward it.16

In addition to mainstream media appearances, Todaro also joined a group of medical professionals advocating for national reopenings, called America’s Frontline Doctors. On July 27, 2020, the group released an anti-mask/pro-HCQ video that the group made while at the White House. The video emphasized reopening, suggesting COVID-19 could be treated (and the economy should be prioritized). "This virus has a cure. It is called hydroxychloroquine, zinc and Zithromax. I know you people want to talk about a mask. Hello? You don’t need [a] mask. There is a cure," the video claims.17 The video was funded by the pro-Trump/pro-reopening group Tea Party Patriots and livestreamed by Brietbart. The video reached over 20 million users within hours.18

The next day, the doctors from the video — Todaro among them — were invited to speak with Vice President Mike Pence and his Chief of Staff.19 “Just finished a great meeting,”Todaro tweeted, “We are doing everything to restore the power of medicine back to doctors. Doctors everywhere should be able to prescribe Hydroxychloroquine without repercussions or obstruction.”20

- 1 Paige Williams, “Trump’s Dangerous Messaging About a Possible Coronavirus Treatment,” The New Yorker, March 27, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/donald-trumps-dangerous-messaging-about-a-possible-coronavirus-treatment.

- 2 Alex Kasprak et al., “Hiding in Plain Sight: PAC-Connected Activists Set Up ‘Local News’ Outlets,” Snopes, March 4, 2019, https://www.snopes.com/news/2019/03/04/activists-setup-local-news-sites/.

- 3 The group also owns the domains americandailystar.com, minnesotanorthernlight.com, mosundaily.com, newenglandstar.com, thedakotastar.com, themichiganstar.com, thencstar.com, theohiostar.com, thepennstar.com, thevirginiastar.com and thewisconsinstar.com.

- 4 Williams, “Trump’s Dangerous Messaging About a Possible Coronavirus Treatment.”

- 5 Jake Pearson, “Republican Billionaire’s Group Pushes Unproven COVID-19 Treatment Trump Promoted,” ProPublica, March 26, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/republican-billionaire-group-pushes-unproven-covid-19-treatment-trump-promoted.

- 6 “Remarks by President Trump, Vice President Pence, and Members of the Coronavirus Task Force in Press Briefing – The White House,” White House Archives, March 19, 2020, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-vice-president-pence-members-coronavirus-task-force-press-briefing-6/.

- 7 Lis Power and Rob Savillo, “Fox News Has Promoted Hydroxychloroquine Nearly 300 Times in a Two-Week Period,” Media Matters for America, April 7, 2020, https://www.mediamatters.org/fox-news/fox-news-has-promoted-hydroxychloroquine-nearly-300-times-two-week-period.

- 8 Matt Gertz, “How Fox News Convinced Trump That It Found a Miracle Cure for Coronavirus,” Media Matters for America, April 6, 2020, https://www.mediamatters.org/fox-news/how-fox-news-convinced-trump-it-found-miracle-cure-coronavirus.

- 9 Matthew Gertz (@MattGertz), “Very Bad Combination: 1) Trump Is Impulsive, Suggestible, Impatient, Likes Quick Fixes 2) Social Distancing Measures Take Several Days to Show Results Because of the Incubation Period 3) Fox Is Telling Him Antimalarials Could Be Miracle Cures & Less Disruption to Economy Needed,” Twitter, March 21, 2020, https://twitter.com/MattGertz/status/1241417322226647040.

- 10 “From the March 19, 2020, Edition of Fox News’ ‘The Ingraham Angle,’” Media Matters for America, https://www.mediamatters.org/media/3860806.

- 11 Matt Gertz, “How Fox News Convinced Trump That It Found a Miracle Cure for Coronavirus.”

- 12Dawn Kopecki, “Coronavirus: NY Gov. Cuomo Says State to Start Clinical Drug Trial, Authorizes Temporary Hospitals, Asks US to Nationalize Medical Supply Buying,” CNBC, March 22, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/22/coronavirus-ny-gov-cuomo-says-state-to-start-clinical-drug-trial-authorizes-temporary-hospitals-asks-us-to-nationalize-medical-supply-buying.html.

- 13 “State Action on Hydroxychloroquine and Chloroquine Access,” Lupus Foundation of America, July 30, 2020, http://www.lupus.org/advocate/state-action-on-hydroxychloroquine-and-chloroquine-access.

- 14 “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: Daily Roundup March 30, 2020,” FDA, July 17, 2020, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-daily-roundup-march-30-2020.

- 15 Libby Cathey, “Timeline: Tracking Trump alongside Scientific Developments on Hydroxychloroquine,” ABC News, August 8, 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/Health/timeline-tracking-trump-alongside-scientific-developments-hydroxychloroquine/story?id=72170553.

- 16 Philip Bump, “The Rise and Fall of Trump’s Obsession with Hydroxychloroquine.”

- 17 Daniel Funke, “Don’t Fall for This Video: Hydroxychloroquine Is Not a COVID-19 Cure,” Kaiser Health News, July 31, 2020, .

- 18 Brandy Zadrozny and Ben Collins, “Dark Money and PAC’s Coordinated ‘reopen’ Push Are behind Doctors’ Viral Hydroxychloroquine Video,” NBC News, July 28, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/social-media/dark-money-pac-s-coordinated-reopen-push-are-behind-doctors-n1235100.

- 19Justine Coleman, “Pence Met with Doctors from Viral Video Containing False Coronavirus Claims,” The Hill, July 27, 2020, https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/509673-pence-met-with-doctors-from-viral-video-containing-false-coronavirus.

- 20 James Todaro (@JamesTodaroMD), “Just Finished a Great Meeting with Vice President Mike Pence and His Chief of Staff. We Are Doing Everything to Restore the Power of Medicine Back to Doctors. Doctors Everywhere Should Be Able to Prescribe Hydroxychloroquine without Repercussions or Obstruction.,” Twitter, July 28, 2020, https://twitter.com/JamesTodaroMD/status/1288247491385794566.

STAGE 4: efforts

Academic institutions, social media platforms, scientists, professional associations and the mainstream media1 quickly warned that there was no proof hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine could treat COVID-19.

But the spread of the HCQ theory proved challenging to mitigate, as the claim was being pushed by figures of authority and many journalists in the right-wing media ecosystem and beyond. Critical press reported on Trump’s and warned against the idea that the drugs were a cure-all. Many research articles and individuals went on record to try to disarm the myth of HCQ as a treatment, particularly as individuals increasingly were sickened or overdosed on the medication.2

Yet, despite the efforts of medical authority figures to debunk Trump’s HCQ claims, right-wing media outlets and right-wing medical personnel continued to support the theory, and some outlets continued to push this medication as a possible treatment.3

It is worth noting that by the time the HCQ claims had reached widespread amplification, it became difficult to separate what was a direct mitigation of Todaro and Rigano’s Google document and what was a mitigation of HCQ theories and Trump’s ideas about and comments on HCQ more generally.

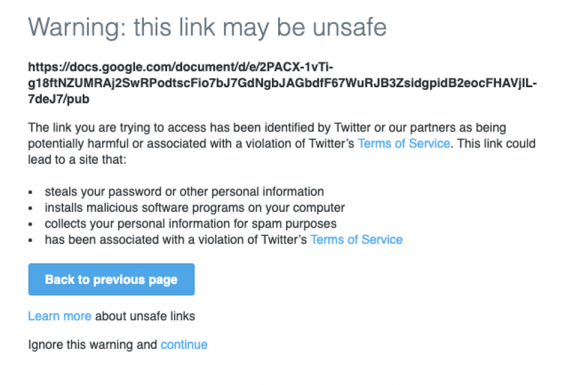

Google took the paper down in late March for violating its terms of service.4 Todaro appealed the decision, and Google reversed it on July 29, 2020.5 As of writing in February 2021, when the link is clicked via Todaro’s original tweet, a warning message appears before users can access the link. The label explains that the Google doc violates Twitter’s terms of service (figure 4 below), although the exact reason for the warning is unclear. Despite this warning, however, Twitter has not labeled or removed the tweet itself.

- 1 Williams, “Trump’s Dangerous Messaging About a Possible Coronavirus Treatment.”

- 2 Eli S. Rosenberg et al., “Association of Treatment With Hydroxychloroquine or Azithromycin With In-Hospital Mortality in Patients With COVID-19 in New York State,” JAMA Internal Medicine 323, no. 24 (June 23, 2020): 2493, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.8630.

- 3 Jeff Colyer and Daniel Hinthorn, “These Drugs Are Helping Our Coronavirus Patients,” Wall Street Journal, March 22, 2020, sec. Opinion, https://www.wsj.com/articles/these-drugs-are-helping-our-coronavirus-patients-11584899438; Jason Puckett and Linda Johnson, “VERIFY: The AMA Did Not Change Its Stance on Hydroxychloroquine and COVID-19,” Kare 11, December 16, 2020, https://www.kare11.com/article/news/verify/ama-stance-hydroxy-covid-unchanged/507-76cac7cc-bd0d-4c21-8771-06949c2220ae.

- 4 Tina Nguyen, “How a Chance Twitter Thread Launched Trump’s Favorite Coronavirus Drug,” Politico, April 7, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/04/07/twitter-thread-launched-trump-coronavirus-drug-170557.

- 5 James Todaro (@JamesTodaroMD), “After 4 Mos of Appeals since It Was Taken down, Google Finally Uncensored Our Initial Paper on HCQ in Treatment of COVID-19. Https://T.Co/GCgJDxhAjV It’s Strange Google Reversed This Decision IMMEDIATELY before Appearing in Front of Congress Today to Discuss Censorship,” Twitter, July 30, 2020, https://twitter.com/JamesTodaroMD/status/1288694517848211457; Didi Rankovic, “Google Censors Google Doc of Medical Hydroxychloroquine Coronavirus Treatment Trial Paper,” Reclaim the Net, March 25, 2020, https://reclaimthenet.org/google-censors-google-doc-hydroxychloroquine/.

In addition, the video by America’s Frontline Doctors has since been removed by Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter for its medical inaccuracies.1 Trump and Donald Trump, Jr. had shared the video. Twitter penalized Donald Trump, Jr. for sharing the video by locking his account for 12 hours.2

Stanford Healthcare posted an “IMPORTANT NOTICE” to its site stating, “A widely circulating Google document claiming to have identified a potential treatment for COVID-19 in consultation with Stanford’s School of Medicine is not legitimate. Stanford Medicine was not involved in the creation of this document, nor have we published a study showing the effectiveness of this drug.”3

Some right-wing conservatives amplified President Trump's HCQ push, while others on his team and the World Health Organization cautioned individuals not to take the drug for the treatment of COVID-19.4 On March 20, one day after Trump announced HCQ as a possible treatment, Director of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Dr. Anthony Fauci went on the record to discourage use of the drug, explaining that the evidence was anecdotal.5

The study published by Rauolt (who had given his data to Todaro and Rigano to tweet) in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents was roundly criticized for overgeneralizing based on a small sample size, only counting the twenty patients who finished the course of treatment. Others who dropped out or died during treatment were not included in final statistics.6 It was later retracted.7

Medical and regulatory agencies and organizations also warned against the use of HCQ. For example, the FDA warned against hydroxychloroquine outside of hospitals.8 The results of clinical trials were publicized, describing a risk of cardiac arrest.9 Likewise, on April 8, the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Rhythm Society put out a joint statement about the dangers of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for patients with existing heart conditions.10 On July 1, the FDA published their findings and focused on warning the public about the severe risks and heart complications associated with taking HCQ.11

E-commerce companies such as Amazon, eBay, and Walmart received millions of searches related to the purchase of chloroquine, following Trump and Fox News’ coverage. Retailers published warnings and withheld products that might contribute to the use of HCQ and chloroquine for treating COVID-19. eBay took the largest step by removing chloroquine sales from its site completely.12 Google, as the leading search site, responded to COVID-19 by adding an educational component to their search results related to the pandemic; this also included unapproved COVID-19 treatments.

- 1 Sam Shead, “Facebook, Twitter and Pull ‘false’ Coronavirus Video after It Goes Viral,” CNBC, July 28, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/28/facebook-twitter-youtube-pull-false-coronavirus-video-after-it-goes-viral.html; Kevin Liptak, “Some Doctors Met with Pence after Their Group’s Video Was Removed for Misleading Info,” CNN, July 29, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/29/politics/mike-pence-doctors-misinformation/index.html.

- 2 Sheera Frenkel and Davey Alba, “Misleading Hydroxychloroquine Video, Pushed by the Trumps, Spreads Online,” The New York Times, July 28, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/28/technology/virus-video-trump.html.

- 3 “Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Resource Center,” https://stanfordlab.com/patient-information/coronavirus-resource-center.html.

- 4“WHO Discontinues Hydroxychloroquine and Lopinavir/Ritonavir Treatment Arms for COVID-19,” World Health Organization, July 4, 2020, https://www.who.int/news/item/04-07-2020-who-discontinues-hydroxychloroquine-and-lopinavir-ritonavir-treatment-arms-for-covid-19; Ankit Kumar, “WHO Advises against Use of Hydroxychloroquine Even as ICMR Approves,” India Today, May 23, 2020, https://www.indiatoday.in/science/story/who-advises-against-use-of-hydroxychloroquine-even-as-icmr-approves-1681037-2020-05-23.

- 5 “Remarks by President Trump, Vice President Pence, and Members of the Coronavirus Task Force in Press Briefing – The White House,” White House Archives, March 20, 2020, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-vice-president-pence-members-c-oronavirus-task-force-press-briefing/; “Caution Recommended on COVID-19 Treatment with Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease,” American Heart Association, April 8, 2020, https://newsroom.heart.org/news/caution-recommended-on-covid-19-treatment-with-hydroxychloroquine-and-azithromycin-for-patients-with-cardiovascular-disease-6797342.

- 6 Williams, “Trump’s Dangerous Messaging About a Possible Coronavirus Treatment.”

- 7 Marcus, “Hydroxychloroquine-COVID-19 Study Did Not Meet Publishing Society’s ‘Expected Standard.’”

- 8 Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, “FDA Cautions against Use of Hydroxychloroquine or Chloroquine for COVID-19 Outside of the Hospital Setting or a Clinical Trial Due to Risk of Heart Rhythm Problems,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, July 1, 2020, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-drug-safety-podcasts/fda-cautions-against-use-hydroxychloroquine-or-chloroquine-covid-19-outside-hospital-setting-or.

- 9 Eli S. Rosenberg et al., “Association of Treatment With Hydroxychloroquine or Azithromycin With In-Hospital Mortality in Patients With COVID-19 in New York State.”

- 10 Libby Cathey, “Timeline: Tracking Trump alongside Scientific Developments on Hydroxychloroquine.”

- 11 Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, “FDA Cautions against Use of Hydroxychloroquine or Chloroquine for COVID-19 Outside of the Hospital Setting or a Clinical Trial Due to Risk of Heart Rhythm Problems.”

- 12Michael Lui, Theodore Caputi, and Mark Dredze, “Internet Searches for Unproven COVID-19 Therapies in the United States,” JAMA Internal Medicine 180, no. 8 (April 29, 2020): 1116–18, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1764.

STAGE 5: Adjustments by campaign operators

There has been no adaptation to this particular campaign, but HCQ advocates continued to iterate after Trump’s prominent amplification of the .

It appears that Todaro and Rigano have not pushed hydroxychloroquine as a remedy since the summer of 2020. Rigano’s last tweet about it was on May 4. On August 2, he appeared on Charlie Kirk’s show to discuss hydroxychloroquine. On August 8, he made the case for hydroxychloroquine as a guest on Steve Bannon’s War Room: Pandemic1 (Bannon appeared in an August 5 YouTube video promoting both the drug and his upcoming episode).2 His last tweet about HCQ was posted on August 12. Since then, he has pivoted to tweets that sow doubt about the coronavirus vaccine.3

Even without the influence of Todaro and Rigano, however, politically adopted support for HCQ and chloroquine continued to resurface. The Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, for example, held a hearing about HCQ on November 19, which included several HCQ advocates.4 At the time of writing, pro-HCQ content can still be found on social media.5

On the second day of the Biden administration, Dr. Fauci closed the chapter on hydroxychloroquine as a coronavirus cure. During a White House press briefing on January 21, 2021, he said, “Obviously I don't want to be going back over history, but it was very clear that there were things that were said — be it regarding things like hydroxychloroquine and other things like that — that really was uncomfortable because they were not based on scientific fact.”6

- 1 “Ep 324- Pandemic: National Town Hall, The Case for Hydroxy Pt. 2 (Dr. James Todaro, Dr. Elizabeth Vliet, Dr. Li Meng Yan, and Senator Ron Johnson) - OFFICIAL Steve Bannon’s War Room: Pandemic,” War Room: Pandemic, August 8, 2020, https://pandemic.warroom.org/2020/08/08/ep-324-pandemic-national-town-hall-the-case-for-hydroxy-pt-2-dr-james-todaro-dr-elizabeth-vliet/.

- 2 G TV, The War between Zeng and Xi Will Be the Most Horrifying Political Warfare in Chinese History; Americans Named Dr. Yan “Captain Marvel” [English Subtitles] (YouTube, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mVrCRm-KXvE.

- 3James Todaro (@JamesTodaroMD), “For Anyone Considering the Pfizer Vaccine, Know That You Are Getting an EXPERIMENTAL Vaccine. You Are Participating in a Study Looking for Adverse Events Think Twice If You Are under 50 Yrs Old with an IFR under 0.02%. Image below from the FDA’s EUA for the Pfizer Vaccine. Https://T.Co/MggbV8PBe5,” Twitter, December 14, 2020, https://twitter.com/JamesTodaroMD/status/1338591290410332160.

- 4According to Dr. Ashish Jha, who also spoke at the hearing, “Neither Ron Johnson, the Wisconsin Republican senator who is the chairman of the committee, nor his chosen witnesses — three doctors who have pushed hydroxychloroquine — displayed more than a passing interest in evidence.” In arguing for continued public health protections while we wait for mass vaccination, Dr. Jha was condemned by right-wing publications for using evidence as his argument. Source: Ashish Jha, “Why Is Congress Still Discussing Hydroxychloroquine?,” The New York Times, November 24, 2020, sec. Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/24/opinion/hydroxychloroquine-covid.html.

- 5 “HCQ - Twitter Search,” Twitter, March 5, 2020, https://twitter.com/search?q=hcq.

- 6Alana Wise, “After Sparring With Trump, Fauci Says Biden Administration Feels ‘Liberating,’” NPR, January 21, 2021, https://www.npr.org/sections/president-biden-takes-office/2021/01/21/959378061/after-sparring-with-trump-dr-fauci-says-biden-administration-feels-liberating.

Cite this case study

Joan Donovan, Jennifer Nilsen, Gabrielle Lim, Nikhil George, Danielle Levin, and Jessica Leon, "Trading Up the Chain: The Hydroxychloroquine Rumor," The Media Manipulation Case Book, August 12, 2021, https://casebook-static.pages.dev/case-studies/trading-chain-hydroxychloroquine-rumor.