Networked Harassment: How a Hashtag Campaign Targeted AOC in the Wake of the January 6 Capitol Riots

Overview:

Nearly one month after a violent mob stormed the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez took to Instagram Live to share a detailed, emotional account of her experience being evacuated by Capitol police from her office during the insurrection. This testimony prompted news articles as well as reactions from the public. During the February 1 social media broadcast, Ocasio-Cortez also revealed that she is a survivor of sexual assault. Almost immediately after the livestream, critics of Ocasio-Cortez began to publicly question the validity of the representative’s story across social media platforms, suggesting that she had exaggerated her experience on January 6—and in some instances, that she had fabricated the sexual assault claim. Campaign operators shared misinfographics as evidence that Ocasio-Cortez was not in harm’s way on January 6 as well as viral slogan hashtags and memes in order to spread the campaign across social media platforms. The campaign managed to trade up the chain via right-wing media influencers and partisan media in the days that followed, resulting in recognition by the target and political adoption on the part of at least one Republican representative. In reaction to the criticism, Ocasio-Cortez’s supporters waged a counter hashtag campaign on Twitter, attempting to drown out users who disputed Ocasio-Cortez’s experience or questioned the sincerity of her testimony. This case demonstrates the power of community mitigation in disrupting the cycle of . Whereas organized, top-down efforts aren’t always effective at mobilizing supporters online, this case shows that organic can be a powerful force against manipulation campaigns.

Background:

Ocasio-Cortez has been a pioneer in Congress for using social media—including Live—for testimonials and connecting with constituents.1 As one of the youngest members of Congress, a woman of color, and a high-profile member of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, Ocasio-Cortez has amassed a large online following,2 and has become a frequent target for harassment and ire from her ideological opposites and those who express prejudice against women or people of color.3

Online disparagement of Ocasio-Cortez often takes the form of (sometimes racist and/or sexist) .4 Images of the representative crying during a 2018 protest in Tornillo, Texas are regularly shared and edited as memes in an effort to prove that Ocasio-Cortez is a liar who uses her emotions for political gain.5 The image displayed in figure 1, for example, has been the subject of several fact-checks from Snopes and other debunking ,6 after a 2019 rumor suggested that the photo had been “staged” by Ocasio-Cortez as a political stunt to raise awareness about family separation and the detainment of migrant children at the Southern US border.7

- 1Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Black Lives Matter Instagram Live | Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, , 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L1OYbwfUGaM; Tayla Minsberg, “How Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Is Bringing Her Instagram Followers Into the Political Process,” The New York Times, November 16, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/16/us/politics/ocasio-cortez-instagram-congress.html; Antonio García Martínez, “How Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Shapes a New Political Reality,” Wired, January 9, 2019, https://www.wired.com/story/how-alexandria-ocasio-cortez-shapes-new-political-reality/.

- 2Analysis by Chris Cillizza Editor-at-large CNN, “The Absolutely Remarkable Social Media Power of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez | CNN Politics,” CNN, July 24, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/24/politics/aoc-ted-yoho-cspan/index.html.

- 3Jane Coaston, “Why Conservatives Love to Hate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez,” Vox, August 20, 2018, https://www.vox.com/explainers/2018/8/20/17674910/conservatives-republicans-ocasio-cortez-democratic-socialist-2018-midterms.

- 4Lam Thuy Vo, “Why Is Everyone So Obsessed With AOC? Let’s Analyze The Memes,” BuzzFeed News, May 3, 2019, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/lamvo/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-aoc-conservatives-liberals-meme.

- 5“AOC Visiting Migrant Detention Facility,” Know Your Meme, accessed July 26, 2021, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/aoc-visiting-migrant-detention-facility.

- 6Bethania Palma, “Does an Image Show AOC Fake-Crying at a Migrant Camp?,” Snopes.com, July 1, 2019, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/aoc-empty-parking-lot/.

- 7Lukas Mikelionis, “AOC’s Office Denies Claims That Photos near Migrant Detention Center Were Staged: ,” Fox News, June 27, 2019, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/ocasio-cortez-mocked-staged-emotional-photoshoot-detention-facility; Ciara O’Rourke and Stefanie Pousoulides, “No, This Isn’t a Photo of Alexandria Ocasio Cortez Crying over a Parking Lot,” PolitiFact, July 22, 2019, https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2019/jul/22/viral-image/no-isnt-photo-aoc-crying-over-parking-lot/.

Her supporters and detractors alike often call Ocasio-Cortez by her acronymized nickname: AOC, which in its own way functions as a unique keyword on social media and as a catchy meme in both visual, written, and oral content.

STAGE 1: Manipulation Campaign Planning and Origins

On February 1, 2021, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez broadcasted an Instagram Live video in which she gave a detailed account of her experience during the insurrection at the US Capitol three weeks earlier, on January 6.1

Many of the Capitol rioters left digital footprints of their behavior that day2 —from tweets to Zello chat logs3 to livestream videos.4 Contained within this ephemera is evidence that people on the ground were looking for AOC specifically during the storming of the main Capitol building.5 Since AOC has been a regular target of from the right, many in both the media and the public who watched in real time had voiced their concerns online over her safety on the day of the insurgency.6 On the evening of the attack, she announced that she was safe and that she would say more later.7 After the event, interest grew in hearing her full account of the day.

“I’m hopping on Live today to talk about what happened at the Capitol,” she told her audience on February 1. “A lot went on, a lot led up to what went on, and I think it’s important to talk about it.”8

During the February 1 broadcast, Ocasio-Cortez gave an emotional personal testimony describing hiding from insurrectionists in her office during the storming of the Capitol, hearing men’s voices outside the door asking where she was, and being terrified for her life.

“The reason I think it’s important to share is because so many of the people who helped perpetrate and who take responsibility for what happened at the Capitol are trying to tell us to move on...We cannot move on without accountability. We cannot heal without accountability,” she said.

Before her retelling of the insurrection, she revealed that she is a “survivor of a sexual assault,” and that the events of January 6 “triggered” feelings of trauma associated with that assault.

“The reason I'm getting emotional in this moment is because these folks who tell us to move on, that it's not a big deal, that we should forget what's happened, or even telling us to apologize, these are the same tactics of abusers,” she said. “And I'm a survivor of sexual assault, and I haven't told many people that in my life, but when we go through trauma...Trauma compounds on each other.”

Ocasio-Cortez continued, “The reason why I have hesitated to tell this story has to do with some of that trauma...As a survivor, I struggle with the idea of being believed. And what's odd is that I am in a job where people are constantly calling me untruthful or that I'm exaggerating etc., so there's a great irony in that.”9

The rest of her 90-minute-long testimony focused specifically on what she had experienced on January 6, which included hearing someone—who she later realized was a Capitol police officer helping with the evacuation—forcing their way into her office while she hid in a bathroom.10

During and in the hours after the livestream, short clips featuring the most emotional and harrowing moments from Ocasio-Cortez’s testimony immediately began to circulate and go viral on Twitter.11 Written summaries of her account,12 along with posts praising Ocasio-Cortez for her bravery and calls for accountability quickly became the most common reaction to her testimony on the platform.13

However, at the same time, a smaller number of Twitter users—many of them with fewer than a hundred followers—began questioning the veracity of Ocasio-Cortez’s recollection of events,14 sometimes using hashtags meant to undermine her credibility.15

The heightened attention paid to specific details from the testimony, such as her exact location at the time of the storming, and whether she actually believed her office had been breached by rioters, may be—at least in part—due to the decontextualized and sensationalized nature of the viral clips being shared by her supporters. Although the full, unedited broadcast was uploaded to Ocasio-Cortez’s Instagram account and YouTube channel shortly after the livestream ended,16 the viral Twitter clips separated her words from their original context, thus creating confusion around certain details and claims from her testimony.

Two of the earliest hashtags employed by Ocasio-Cortez’s critics, #AlexandriaOcasioSmollet and #AOCSmollett, compared Ocasio-Cortez to actor Jussie Smollett, who had previously been embroiled in a scandal related to his claims about being the victim of a hate crime, which were later discredited when a concluded that Smollett had fabricated the incident.17

Although these hashtags would later be adopted by prominent right-wing social media and amplified, the Technology and Social Change team is not aware of any strategic or coordinated amplification of the campaign on the part of unverified, relatively small Twitter accounts.

Meanwhile, on 4Chan’s Politically Incorrect board (/pol/), anonymous users also began to invalidate or question the veracity of Ocasio-Cortez’s testimony almost immediately. In the case of /pol/, instead of taking issue with specific details pertaining to the congresswoman’s retelling of events on January 6, /pol/ anons began questioning the motivations behind Ocasio-Cortez’s self-identification as a victim of sexual assault. Many anons expressed that they didn’t believe her story,18 suggesting she had fabricated the sexual assault in order to ”play the victim” and garner media attention.19

Within 24 hours of the original Instagram livestream, more than 20 threads dedicated to her testimony had been created on the /pol/ board, containing more than 300 posts in total.20 Some posts were blatantly racist and misogynist,21 suggesting that Ocasio-Cortez’s claims were proof women should not hold public office,22 and professing outrage that she would “use sexual assault” to drum up sympathy.23

“Is there anything she won’t say to get attention?” wrote a /pol user in one of the earliest relevant threads from the day of the livestream.24

“I was wondering when she was gonna play this card,” wrote another anon on February 2.25

For /pol/ regulars, her livestreamed testimony was just the latest topic of interest in an on-going discussion related to Ocasio-Cortez. On the board, anons regularly scrutinize her politics,26 as well as her physical appearance.27 It is not uncommon for anons to post about their desire to have sex with her,28 sexually assault her,29 or physically harm her.30

The stark difference in simultaneous critique’s of AOC’s testimony on Twitter and /pol/ is indicative of a cultural divide that exists between the two platforms. Whereas 4chan generally—and /pol/ especially—has a long history of distrusting victims of sexual assault and making light of violence against women in general,31 Twitter—the original platform of the #MeToo Movement—tends to have a more liberal user base, and though Twitter conversations about the particularly potent wedge issue of sexual assault take place on the platform, the culture is not overwhelmingly tolerant of sexist or violent rhetoric.32

- 1Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, What Happened at the Capitol Instagram Live | Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (YouTube, 2021), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fWNWoNaImQA.

- 2Sara Morrison, “The Capitol Rioters Put Themselves All over Social Media. Now They’re Getting Arrested.,” Vox, January 7, 2021, https://www.vox.com/recode/22218963/capitol-photos-legal-charges-fbi-police-facebook-twitter.

- 3“The Zello Tapes: The Walkie-Talkie App Used During The Insurrection | On the Media,” WNYC Studios, January 15, 2021, https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/otm/segments/zello-tapes-walkie-talkie-app-used-during-insurrection-on-the-media.

- 4Philip Bump, “Analysis | The Capitol Mob Recorded Its Own History. Now, Volunteers Are Trying to Preserve the Record,” Washington Post, January 7, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/01/07/capitol-mob-recorded-its-own-history-now-volunteers-are-trying-preserve-record/; Kat Tenbarge, “White Nationalist Baked Alaska Livestreamed Himself from inside the US Capitol as He Joined Rioters,” Insider, January 6, 2021, https://www.insider.com/washington-dc-protest-livestream-baked-alaska-us-capitol-riot-trump-2021-1.

- 5Jaclyn Peiser, “Capitol Rioter Garret Miller Threatened to Assassinate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Feds Say,” Washington Post, January 25, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/01/25/aoc-garret-miller-capitol-riot/.

- 6Kristin (@kristinbig1), “I’m Worried about @AOC, @Ilhan, @CoriBush, @RashidaTlaib, @AyannaPressley. How Can Any of the Feel Safe in Their Workplace Going Forward? How Do They Know Which Capitol Police Will Protect Them & Which Will Open the Barricades for the Mob?,” , January 6, 2021, https://twitter.com/kristinbig1/status/1347087883753156608; Megan (@DMeganR Rutherford, “Where Is @aoc and Please Update Her Status. I Am so Effing Worried about Her and Her Compatriots.,” Twitter, January 6, 2021, https://twitter.com/DMeganR/status/1346921043747770369.

- 7Alexandria (@AOC) Ocasio-Cortez, “I’m Okay.,” Twitter, January 6, 2021, https://twitter.com/AOC/status/1346968581741928451".

- 8 Ocasio-Cortez, What Happened at the Capitol Instagram Live | Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

- 9Ibid.

- 10Ryan (@ryepastrami) Khosravi, “.@AOC Telling a Story about Someone Literally Banging on Her Office Door, Screaming ‘Where Is She?’ While She Hid.(1/2) Https://T.Co/ORgrjNWhlY,” Twitter, February 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/ryepastrami/status/1356441140455739392.

- 11grant🧔🏻 (@urdadssidepiece), “This Was One of the Most Heartbreaking Moments of AOC’s IG Live,” Twitter, February 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/urdadssidepiece/status/1356444065370427394; Ryan (@ryepastrami) Khosravi ✨, “.@AOC Telling a Story about Someone Literally Banging on Her Office Door, Screaming ‘Where Is She?’ While She Hid.(1/2) Https://T.Co/ORgrjNWhlY,” Twitter, February 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/ryepastrami/status/1356441140455739392; PatriotTakes 🇺🇸 (@patriottakes), “.@AOC Describes Her Thoughts about Dying as She Hid from a Domestic Terrorist Who Had Breached Her Office and Was Screaming, ‘Where Is She? Where Is She?’ Https://T.Co/FTLzfwJysZ,” Twitter, February 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/patriottakes/status/1356438574212743168; Robin (@robinkelly1) Kelly 😷, “‘I Started to Hear These Yells, “Where Is She? Where Is She?” And I Thought to Myself “They Got inside”. I Thought I Was Going to Die.’ @AOC on the Trauma of the Fascist Insurrection That’s Being Downplayed by @GOP and Far-Right Media. Https://T.Co/C7JMv7pkrf,” Twitter, February 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/robinkelly1/status/1356497582713958408.

- 12Carlos (@carloseats) Hernandez, “AOC Is Saying on IG Live She Received Messages from Other Member of Congress That They Knew and Were Hearing from Trump People and Republicans That There Was Violence Expected on Wednesday (Jan. 6).,” Twitter, February 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/carloseats/status/1356426580290121729.

- 13Kathy (@kathygriffin) Griffin, “Watched This Whole @AOC Live IG. Grateful for Her Honesty and Bravery.,” Twitter, February 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/kathygriffin/status/1356471945047339008; David (@davidmweissman) Weissman, “After Hearing AOC’s IG Tonight, I’m More Furious That Kevin McCarthy Has yet to Expel Majorie Taylor Greene & Lauren Boebert for Their Incitement. As an Army Veteran Who Took an Oath to Defend the Constitution; I Demand That @GOPLeader Upholds His Oath & #ExpelTheSeditionists.,” Twitter, February 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/davidmweissman/status/1356464552259563520.

- 14Kimberly (@kimKBaltimore) Klacik, “I Am Not Calling @AOC a Liar, I Just Want to Point out the Contrast from Her Statement on Twitter the Day of the DigginDave142 (@Dave142Diggin), “@fransquishco @AOC Wow It’s Impressive How Quickly She Can Make up a Lie to Put Her Back in Front of the Camera’s, Obviously This Poor Child Was Starved for Attention!,” Twitter, February 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/Dave142Diggin/status/1356559368846794755; KAD (@KSLAKLD), “@HathorGoddess @CNN Sorry I Just Don’t Believe @AOC She Is so Self Centered & Self Absorbed That Everything Is Big Drama. Mothers in Yemen Cannot Feed Their Children, Think about the Mothers in Syria. @AOC Always Drama,” Twitter, February 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/KSLAKLD/status/1356572941119483907; Clay (@Clayton78153433), “@People4Bernie @AOC One of Our Overloards Playing the Victim Card. I Find It Insulting That She Compares Herself to the Real Victims, Rape Victims, Violence Victims. She Heard People Bearing on the Door While Surrounded by Her Armed Security. Don’t Fall for This Shill,” Twitter, February 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/Clayton78153433/status/1356572929107050496; Hancho pancho (@robingreen12ws), “I Think She Lying so Am Not Frustrated…,” Twitter, accessed via Wayback Machine, February 2, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20210202115906/https://twitter.com/robingreen12ws/status/1356572762073096192; Capitol Riot to Now, Almost a Month Later. A Much Different Picture Painted. Https://T.Co/86B5Ylb6Ta,” Twitter, February 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/kimKBaltimore/status/1356685385074696198..

- 15The Illegitimate Demented Quisling (@TheIllegitimat1), “I’m Thinking She’s Earned It This Time, Perhaps Twice over. #AlexandriaOcasioSmollett,” Twitter, February 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/TheIllegitimat1/status/1356850405620203523; FugitiveMama (@fugitivemama), “November 6. It’s Almost as If She Had a Premonition. Her Talents Are Many. #AOCSmollett Https://T.Co/FHWdW8F2Ox,” Twitter, February 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/fugitivemama/status/1356476906875416576.

- 16Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, “What Happened at the Capitol.,” Instagram, February 1, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CKxlyx4g-Yb/?hl=en; Ocasio-Cortez, What Happened at the Capitol Instagram Live.

- 17Ben Kesling and Erin Ailworth, “Actor Jussie Smollett Indicted on Charges of Faking Hate Crime,” The Wall Street Journal, February 11, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/actor-jussie-smollett-charged-again-with-faking-hate-crime-in-chicago-11581460576.

- 18Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306224959,” , accessed via 4plebs, February 2, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/306224959/#q306227408.

- 19Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306224959,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, February 2, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/306224959/#306229744; Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306197211,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, February 1, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/306197211/#306197211.

- 20Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Searching for Posts That Contain ‘AOC’ and Posts after 2021-02-02 and Posts before 2021-02-03.,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, accessed July 26, 2021, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/search/text/AOC/start/2021-02-02/end/2021-02-03/.

- 21Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306246397,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, February 2, 2021, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/306246397/#306274746; Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306246397,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, February 2, 2021, http://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/306246397/#306246619.

- 22Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306197211,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, February 1, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/306197211/#306217403.

- 23Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306246397.”

- 24 Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306197211.”

- 25Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306224959,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, February 2, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/306224959/#q306227094.

- 26Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306180123,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, February 1, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/306180123/#306180123.

- 27Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #303085400,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, January 16, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/303085400/#q303085400; Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #297430988,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, December 18, 2020, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/297430988/#297430988; Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #303745496,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, January 19, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/303745496/#q303745496.

- 28Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #297471422,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, December 18, 2020, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/297471422/#q297471482.

- 29 Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #305610438,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, January 28, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/305610438/#q305611980.

- 30Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #274292824,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, August 26, 2020, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/274292824/#274293326.

- 31Melanie Ehrenkranz, “Inside 4chan’s Campaign to Expose the ‘next Fake Trump Victim,’” Mic, October 13, 2016, https://www.mic.com/articles/156697/next-fake-trump-victim-4chans-campaign-to-smear-trumps-accusers; Angela Nagle, “The New Man of 4chan,” The Baffler, no. 30 (2016): 64–76.

- 32Monica Anderson and Skye Toor, “How Social Media Users Have Discussed Sexual Harassment since #MeToo Went Viral,” Pew Research Center, October 11, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/10/11/how-social-media-users-have-discussed-sexual-harassment-since-metoo-went-viral/.

STAGE 2: Seeding Campaign Across Social Platforms and Web

On February 3, right-wing media influencer Jack Posobiec tweeted an article from the partisan website redstate.com with the headline “AOC Wasn't Even in the Capitol Building During Her 'Near Death' Experience.”1 The article called Ocasio-Cortez’s account of the Capitol riots an “overreaction,” and pointed out that her office is located in a separate building from “where all the action was going down.”

The article does not acknowledge, however, that during her Instagram Live broadcast, Ocasio-Cortez never actually claimed to have been in the Capitol Building at the time of the insurrection. The article cites two short clips from the broadcast uploaded to Twitter,2 but neither clip contains the section of the livestream where Ocasio-Cortez says that she was, in fact, in her office in the Cannon Building.3 This suggests that the viral Twitter clips served as recontextualized media that may have contributed to Ocasio-Cortez’s claims being removed from the larger context of her original testimony, and interpreted incorrectly by those looking to characterize her words as a politically-motivated exaggeration of events.

Adopting the claims made in the article, Posobiec also tweeted an annotated map of the Capitol Complex (figure 2) intended to highlight the distance from the Cannon Building, Rep. Katie Porter’s office (where Ocasio-Cortez said she hid after being evacuated from her office by police), and the main Capitol building, where the majority of rioting took place on January 6. The exact origin of the image is unknown.

Posobiec labelled the map as a “fact-check,” suggesting that the distances indicated in the image reveal that Ocasio-Cortez was not actually in danger on the day of the insurrection.4

- 1Jack (@JackPosobiec) Posobiec, “AOC Wasn’t in the Capitol Building During Her ‘Near Death’ Experience Https://T.Co/VoJHtRAKYW,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/JackPosobiec/status/1357017857943601153; Nick Arama, “AOC Wasn’t Even in the Capitol Building During Her ‘Near Death’ Experience,” redstate.com, February 3, 2021, https://redstate.com/nick-arama/2021/02/03/321029-n321029.

- 2grant🧔🏻 (@urdadssidepiece), “This Was One of the Most Heartbreaking Moments of AOC’s IG Live.”

- 3Ocasio-Cortez, What Happened at the Capitol Instagram Live.

- 4Jack (@JackPosobiec) Posobiec, “Fact-Check Https://T.Co/TLoJ3HxcQP,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/JackPosobiec/status/1357028286728187906.

Less than an hour after Posobiec tweeted the image, the same annotated map was posted on /pol/,1 where anonymous users continued to suggest that Ocasio-Cortez had lied about her alleged sexual assault.2 In addition to those doubts, /pol/ users also began discussing the notion that she had lied about her whereabouts and proximity to the riots during the insurrection itself for political gain, a narrative that originated on Twitter.3

In the days that followed, several larger right-wing Twitter accounts and conservative media influencers began using the Smollett-related hashtags on Twitter,4 TikTok,5 and other social media platforms. Some also tweeted the hashtag #AOCLied,6 which predated this specific incident and had been used occasionally on Twitter to attack Ocasio-Cortez’s credibility since 2019.7

Several users, including political commentator Candace Owens, posted images of an emotionally overcome Ocasio-Cortez—taken during a 2018 protest against the detainment of migrant children at the US Mexico border—to suggest that the representative had a history of using emotion to garner media attention.8

- 1Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #306432650,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, February 3, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/306432650/#306432650.

- 2Anonymous, “/Pol/-Politically Incorrect » Thread #306432650.”

- 3Ibid.

- 4Catturd TM (@catturd2), “#AlexandriaOcasioSmollett,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/catturd2/status/1357049674297970691; Benny (@bennyjohnson), “So Important, #AOCSmollett MEME: @grandoldmemes Https://T.Co/SJnTAFWQ8N,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/bennyjohnson/status/1357354441234673665; Charlie (@charliekirk11) Kirk, “If AOC Was a Republican She Would Be Banned from Social Media after Telling Such a Bold-Faced, Dangerous Lie But Because She’s Not, She Doesn’t Even Get a Fact Check. Liberal Privilege Is a Real Thing.,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/charliekirk11/status/1357523496645980160.

- 5Rachel (@rachel_amethyst), #greenscreen #AlexandriaOcasioSmollett 💀💀💀😂😂😂 #funny #sorrynotsorry #gottalaugh #trump #imisstrump #ThisorThatSBLV ( , 2021), https://www.tiktok.com/@rachel_amethyst/video/6925189912887151877?_d=secCgYIASAHKAESMgowV6Z%2FasTx1snuoEpKOLwhInYZC56RJ3wJtvSq6Qu3ZyK0PW4Ibqu4KpHb7EMedH0wGgA%3D&checksum=433a15e4a746b0dc543dd1fd2267b4fe2e06896ad83b12b9e6a85c91e01dee67&language=en&preview_pb=0&sec_user_id=MS4wLjABAAAAjPm8NN1775h-HxFyDF7VF8eabZ0d2chxG2Yxn9o1sBYisYWo3vBgZSDLGNMTjaiY&share_app_id=1233&share_item_id=6925189912887151877&share_link_id=4931697d-5473-43db-86fd-21e340a35a1f&source=h5_m×tamp=1626672240&u_code=dia5eki9lgbg66&user_id=6956698020201579525&utm_campaign=client_share&utm_medium=android&utm_source=copy&_r=1.

- 6#ThePersistence (@ScottPresler), “AOC Wasn’t Even in the Capitol Building during Her ‘near-Death’ Experience. One Big Lie. #AlexandriaOcasioSmollett,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/ScottPresler/status/1357101819718164480; KEEM 🍿(@KEEMSTAR), “I Would like to Remind All the YouTubers & Twitch Streamers That Promoted AOC You’re Just a Stupid as She Is! “AOC Was Not in the U.S. Capitol Building during Her ‘near Death’ Experience. She Was in the Cannon Building. ‘ Rioters Did Not Breach the Cannon Building.’ Https://T.Co/HMcb7nWr90,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/KEEMSTAR/status/1357174472386748423.

- 7Cindy4FreeSpeech (@nalley_a), “@jh45123 #AOCLied She Is a Media Whore. Sure Wish They’d Stop Giving Her Publicity,” Twitter, July 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/nalley_a/status/1146150915914600449.

- 8Candace (@RealCandaceO) Owens, “On a Day in Which #AlexandriaOcasioSmollett Is Trending, Please Never Forget the Time That @AOC Staged a Photo Shoot Dressed in All White at a Parking Lot to Spread Lies about Immigrant Children in Cages. Faking Her Own Attempted Murder Was the next Logical Step. Https://T.Co/Y8mNNowMGy,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/RealCandaceO/status/1357078980197810179.

Owens employed the #AlexandriaOcasioSmollett hashtag on February 3 in a tweet that also asked, “How many men has @AOC falsely accused of heinous acts against her? She seems disturbed.”1

In a now-deleted tweet featuring the #AOCLied hashtag from the same day, former Trump administration strategist and radio talk show host Sebastian Gorka wrote, “She lied about where she was on January 6th. She lied about being in danger. @AOC will lie about anything.”2

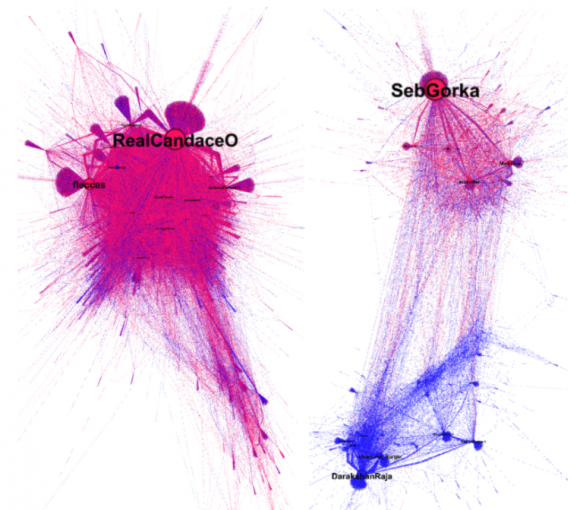

Analysis conducted by the Technology and Social Change team shows that Owens and Gorka received 23.58 percent and 14.57 percent, respectively, of the total retweets containing those specific hashtags. This data suggests that an outsized proportion of the attention paid to this manipulation campaign on Twitter is attributable solely to these two accounts.

- 1Candace (@RealCandaceO) Owens, “Since #AlexandriaOcasioSmollett Is Trending, Let Us All Be Reminded of the Time Ben Shapiro Challenged Her to a Debate, and She Falsely Accused Him ‘Cat-Calling’ Her with ‘Bad Intentions’. How Many Men Has @AOC Falsely Accused of Heinous Acts against Her? She Seems Disturbed. Https://T.Co/Z5prax8WbI,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/RealCandaceO/status/1357177824461881344.

- 2Sebastian (@SebGorka) Gorka DrG, “She Lied about Where She Grew up. She Lied about Where She Was on January 6th. She Lied about Being in Danger. @AOC Will Lie about Anything. #AOClied #AOCisAFraud #ExpelAOC,” Twitter, accessed via archive.is, February 4, 2021, http://archive.is/EuWqG.

Figure 4: Twitter retweet networks for #AlexandriaOcasioSmollett (left) and #AOCLied (right). Each node is a Twitter account, each line connecting nodes is a retweet, and nodes appear larger if they garnered more retweets. Red nodes are confirmed to have participated previously in amplifying claims of electoral fraud during the October-December 2020 period. Credit: Alexei Abrahams.

On the evening of February 3, as Gorka’s tweet went viral, #AOCLied became the top trending hashtag on Twitter, a fact which Jack Posobiec pointed out to his followers,1 effectively signalling that the campaign was successfully gaining traction sitewide.

Over the next two days, the campaign made its way to other social media platforms, and traded up the chain from social media to tabloid news outlets, right-wing media, and eventually mainstream news publications.

For example, on February 4, a New York Post article containing an annotated map of the Capitol complex similar to the one posted by Posobiec was shared to the conservative group “The Silent Majority 2,” which has more than 44,000 followers.2 3 As of writing in June 2021, this particular Facebook post has been shared more than 450 times.4 Similar articles were published by Brietbart,5 the Daily Wire,6 and other right-wing media websites, beginning on February 3.7

The Daily Stormer, a well-known neo-Nazi blog and message board, also published an article featuring another annotated map of the Capitol complex.8

On Reddit, a February 3 post on r/conspiracy containing an embedded tweet from conservative social media personality Samantha Marika claimed that Ocasio-Cortez had been “exposed for lying” about her experience at the Capitol. This post garnered nearly 400 comments in less than 24 hours.9

Also on February 3, the campaign to discredit AOC’s testimony reached Telegram. Several prominent extremist groups,10 alt-right influencers,11 and conspiracy communities12 on Telegram began to accuse Ocasio-Cortez of lying about her experience during the insurrection, oftentimes sharing the annotated map of the Capitol Complex originally posted by Posobiec,13 or a YouTube video titled “Twitter EXPOSES AOC For LYING About the Capitol Riot, SHE WAS NOT IN THE BUILDING,” which, as of July 2021, has garnered more than 109,000 views.14

By February 4, right-wing YouTube personalities Steven Crowder and Tim Pool both posted lengthy videos in which they outlined the “evidence” that Ocasio-Cortez had exaggerated her claims—including the annotated map.15 16 At the time of publishing, Crowder’s video, titled “#AOCLied and I'll Prove it…” has amassed more than 1.3 million views.17

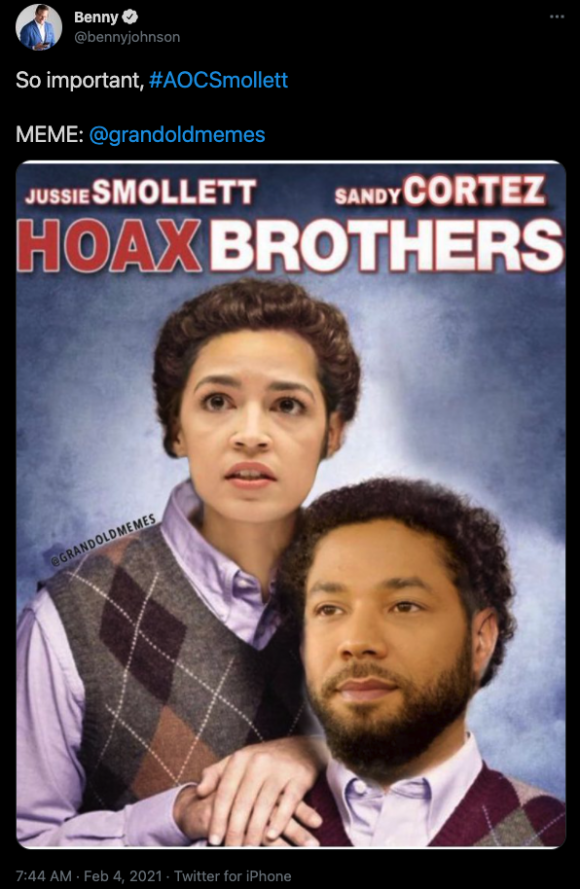

Political cartoons and memes inspired by the viral hashtags also began to bubble up on February 4. Figure 4 displays one such meme—posted by right-wing columnist Benny Johnson on Twitter—which draws on the comparison to Smollet, and was retweeted more than 900 times.18

- 1Jack (@JackPosobiec) Posobiec, “BREAKING: #AOClied Is Now the #1 Trend in the United States Https://T.Co/Z5vCXO4j3T,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/JackPosobiec/status/1357208068480720896.

- 2Emily Jacobs, “AOC Blasted for Exaggerating Her ‘Trauma’ from Capitol Riot Experience,” New York Post, February 4, 2021, https://nypost.com/2021/02/04/aoc-blasted-for-exaggerating-capitol-riot-experience/.

- 3“The Silent Majority 2,” Facebook, accessed July 29, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/The-Silent-Majority-2-297320404365324/.

- 4The Silent Majority 2, “Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Is Being Dubbed ‘Alexandria Ocasio-Smollett’ as Details Emerge That She Exaggerated the Extent of Her ‘Trauma’ from the Capitol Riot, given That She Was Not at the Site of the Siege, but in an Office Building Nearby...,” Facebook, February 4, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=882975962466429&id=297320404365324.

- 5Matthew Boyle, “AOC: Riot Story Challengers ‘Manipulating’ People Over Capitol Complex,” Breitbart, February 4, 2021, https://www.breitbart.com/politics/2021/02/03/aoc-those-challenging-riot-story-manipulating-people-who-dont-know-the-layout-of-capitol-complex/.

- 6Amanda Prestigiacomo, “Report: AOC Was Not Inside Capitol Building During Breach; AOC Responds: Report ‘Manipulative,’” The Daily Wire, accesed via archive.is, February 3, 2021, http://archive.is/U7XVL.

- 7Joel Abbott, “Remember How AOC Said She Was Hiding in Her Office Bathroom While Someone Was Banging on the Door? Turns out It Was Capitol Police.,” Not the Bee, February 3, 2021, https://notthebee.com/article/remember-how-aoc-said-she-was-hiding-in-her-office-bathroom-while-rioters-were-banging-on-the-door-turns-out-she-wasnt-even-in-the-capitol-building.

- 8Andrew Anglin, “AOC Says the Cops Securing Her Office Building Were Part of the ‘Attack’ Conspiracy,” Daily Stormer, February 4, 2021, https://dailystormer.su/aoc-says-the-cops-securing-her-office-building-were-party-of-the-attack-conspiracy/.

- 9Normiesreeee69, “AOC Gets Exposed for Lying about Her *near Death Experience* She Claims to Have Been in Her Office, Which Is Located in the Cannon Building. Rioters Didn’t Breach the Cannon Building.,” Post, R/Conspiracy, February 3, 2021, www.reddit.com/r/conspiracy/comments/lbuqbl/aoc_gets_exposed_for_lying_about_her_near_death/.

- 10@TheWesternChauvinist, “All Commie Bitches Know How to Do Is Take Selfies with They Cell Phone, Eat Hot Chip, and Lie. @TheWesternChauvinist Https://Breaking911.Com/Aoc-Called-out-for-Claim-She-Was-Nearly-Assassinated-during-Capitol-Siege-She-Hits-Back-Saying-It-Was-Actually-Worse/,” , February 2, 2021, https://t.me/TheWesternChauvinist/7206.

- 11@MiloOfficial, “Big Lies Are Easy to Tell and Easy to Recover from. But When You Get Caught Making up Little Details, You Never Recover from It. AOC Could Have Said She Was Scared. Maybe She Was, Looking out of the Window at Something Happening a Couple of Blocks Away. But She Just Had to Take It That Little Bit Further and Say She Saw Someone Stealing Her Shoes. That’s Why She’s Sunk. Pathological Liars Always Add These Little Color Details and It’s the Details That Get You.,” Telegram, February 3, 2021, https://t.me/MiloOfficial/23421.

- 12@HereJoeM, “AOC Lied about Being in the Capitol on January 6th, If You Haven’t Heard. She’s a Complete Fraud and Delusional. I Believe She’s Mentally Ill. 🇺🇸 t.Me/JCMiller,” Telegram, February 4, 2021, https://t.me/HereJoeM/1044.

- 13@disclosetv, “NEW - AOC Was Not in the U.S. Capitol Building during Her ‘near Death’ Experience. She Claims to Have Been in Her Office, Which Is Located in the Cannon Building. Rioters Did Not Breach the Cannon Building. @disclosetv @disclosetv_chat,” Telegram, February 3, 2021, https://t.me/disclosetv/525.

- 14@WEARETHENINETYNINEPERCENT, “Https://Youtu.Be/8SPpBEc6TIk,” Telegram, February 3, 2021, https://t.me/WEARETHENINETYNINEPERCENT/73842.; MR. OBVIOUS, “Twitter EXPOSES AOC For LYING About the Capitol Riot, SHE WAS NOT IN THE BUILDING” (YouTube, 2021), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8SPpBEc6TIk.

- 15StevenCrowder, “#AOCLied and I’ll Prove It... | Louder with Crowder” (YouTube, 2021), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MKxGp8jQzps&t=3s.

- 16Timcast, “I Have PROOF AOC Lied About Her Capitol Story, Its Way WORSE Than You Thought (MAJOR UPDATE)” (YouTube, 2021), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prlmJQAf1ns&t=1s.

- 17StevenCrowder, “#AOCLied and I’ll Prove It... | Louder with Crowder.”

- 18Benny (@bennyjohnson), “So Important, #AOCSmollett MEME: @grandoldmemes Https://T.Co/SJnTAFWQ8N,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/bennyjohnson/status/1357354441234673665.

Meanwhile, on TikTok, several users posted short videos between February 3 and February 6 mocking Ocasio-Cortez’s emotional testimony and calling for her removal from office.1 Many incorporated clips from the livestream and the annotated map that Posobiec had posted on Twitter into their videos.2

Notably, skepticism about the authenticity of Ocasio-Cortez’s sexual assault remained almost exclusive to the /pol/ board on 4chan.

- 1Zoe (@itszoetoyou), Practice Makes Perfect! #aoclied #trump2020 #draintheswamp #aoc #liberal #conservative (TikTok, 2021), https://www.tiktok.com/@itszoetoyou/video/6925944378624068870?_d=secCgYIASAHKAESMgowlggdWMk6aJgj%2BGQVPh1npzav9NRSlJnbrFoMO4ugkEugOUu3aRg49W9gyFc0clbxGgA%3D&checksum=3c85c262637f85e6fd6ff937059d742e1dd307d02c6c57524d66940fd96a79d0&language=en&preview_pb=0&sec_user_id=MS4wLjABAAAAjPm8NN1775h-HxFyDF7VF8eabZ0d2chxG2Yxn9o1sBYisYWo3vBgZSDLGNMTjaiY&share_app_id=1233&share_item_id=6925944378624068870&share_link_id=cd10515c-52d1-476c-a7ba-8454966032ad&source=h5_m×tamp=1622822341&u_code=dia5eki9lgbg66&user_id=6956698020201579525&utm_campaign=client_share&utm_medium=android&utm_source=copy&_r=1; Melissa (@melissa_b98), #greenscreen #aoclied (TikTok, 2021), https://www.tiktok.com/@melissa_b98/video/6925757464394681605?_d=secCgYIASAHKAESMgow4OuF0U42BQuYhZI3ddqmvyoduPuoxtX0rnfn40bcEdofD5U3ozGVdj03uq1DmbRrGgA%3D&checksum=480d1b431f63fe782a4a63d5c61ce22e0c9c39409d7b5485c66e74dbbecbb0cc&language=en&preview_pb=0&sec_user_id=MS4wLjABAAAAjPm8NN1775h-HxFyDF7VF8eabZ0d2chxG2Yxn9o1sBYisYWo3vBgZSDLGNMTjaiY&share_app_id=1233&share_item_id=6925757464394681605&share_link_id=44244d17-fdb8-4fb2-9ca9-d7db83febda9&source=h5_m×tamp=1622822226&u_code=dia5eki9lgbg66&user_id=6956698020201579525&utm_campaign=client_share&utm_medium=android&utm_source=copy&_r=1.

- 2@ralphs_trucking, #stitch with @ralphs_trucking #greenscreen #aocfanclub #aoclied #truthhurts #aocliedjan6 #fypシ #fyp #demoncratsfraud #jan62021 #aoc #dc (TikTok, 2021), https://www.tiktok.com/@ralphs_trucking/video/6925395281987046661?_d=secCgYIASAHKAESMgowTUVxoJ4sNmmkUErIZmq%2B0wCtfl8nwJLroxQaDPcLqb1aRYTMZzoKtxqdUYg6pRFCGgA%3D&checksum=deef1dae5e001beee967009c187c9c5c31920f9dfef74857b471eaf4bc14dc16&language=en&preview_pb=0&sec_user_id=MS4wLjABAAAAjPm8NN1775h-HxFyDF7VF8eabZ0d2chxG2Yxn9o1sBYisYWo3vBgZSDLGNMTjaiY&share_app_id=1233&share_item_id=6925395281987046661&share_link_id=f701af20-a55e-434c-81eb-2cfff0df922d&source=h5_m×tamp=1622140270&u_code=dia5eki9lgbg66&user_id=6956698020201579525&utm_campaign=client_share&utm_medium=android&utm_source=copy&_r=1.

STAGE 3: Responses by Industry, Activists, Politicians, and Journalists

On February 2, the day after her Instagram Live, headlines such as “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Opens Up About Trauma in a Moving and Powerful Instagram Live,”1 ran across the web and were shared widely on social media.2 Her entire testimony received media exposure, much of it laudatory from the mainstream press,3 and left-of-center influencers.4

The revelation of her sexual assault also generated its own news coverage, inspiring headlines such as “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Speaks Out About Surviving Sexual Assault.”5

Later on February 2, Representative Nancy Mace (SC-R)—whose office is located near Ocasio-Cortez’s in the Cannon Building—disputed AOC’s January 6 story, resulting in political adoption of the manipulation campaign. Using her congressional Twitter account, Mace tweeted, “My office is 2 doors down. Insurrectionists never stormed our hallway. Egregious doesn’t even begin to cover it. Is there nothing MSM won’t politicize?”6

In the same tweet, Mace included screenshots from a February 1 Newsweek article that falsely reported that Ocasio-Cortez had claimed “rioters had actually entered her office” during her Instagram Live broadcast.7 Newsweek issued a correction on February 3, but the screenshot containing the false claim remains available on Mace’s Twitter account at the time of publishing.8 In spite of the correction, Mace repeated her dispute of AOC’s story on February 4, using her personal Twitter account.9

As the campaign continued to spread, Ocasio-Cortez responded to several prominent critics in real time.

In a public reply to Posobiec’s February 3 tweet containing the annotated map, Ocasio-Cortez wrote, “This isn’t a fact check at all. Your arrows aren’t accurate. They lie about where the mob stormed & place them further away than it was. You also fail to the convey *multiple* areas people were trying to storm. It wasn’t 1. You also failed to show tunnels. Poor job all around.”10

Ocasio-Cortez addressed the manipulation campaign more generally on Twitter that same day, saying, “This is the latest manipulative take on the right. They are manipulating the fact that most people don’t know the layout [of] the Capitol complex. We were all on the Capitol complex - the attack wasn’t just on the dome. The bombs Trump supporters planted surrounded our offices too.”11

Ocasio-Cortez also replied to Mace on February 4, tweeting, “This is a deeply cynical & disgusting attack, @NancyMace. As the Capitol complex was stormed & people were being killed, none of us knew in the moment what areas were compromised. You previously told reporters yourself that you barricaded in your office, afraid you’d be hurt.”12

In a separate thread, AOC continued to address Mace directly:

“@NancyMace who else’s experiences will you minimize? Capitol Police in Longworth? Custodial workers who cleaned up shards of glass? ...All I can think of w/ folks like her dishonestly claiming that survivors are exaggerating are the stories of veterans and survivors in my community who deny themselves care they need & deserve bc they internalize voices like hers saying what they went through ‘wasn’t bad enough.’”13

On February 5, Mace—who, during a 2019 debate about a South Carolina abortion bill, disclosed that she had been raped at age 1614 —tweeted a link to an opinion piece published in conservative news outlet the Washington Examiner with the headline, “AOC attacks GOP rape survivor Nancy Mace for silencing rape survivors.”15 16

The same day, Representative Katie Porter came to Ocasio-Cortez’s defense during a CNN interview with Chris Cuomo, calling disputes of the representative’s account “absolutely untrue,” and confirming that she and AOC had sheltered in place together on the day of the insurrection and had, in fact, been afraid for their lives.17

“We had no way to know if and when the people who had penetrated the Capitol were coming through the tunnels to get us,” Porter told Cuomo. “No way to know if the voices that we heard in the hallway were those of police officers or those of the mob.”18

- 1The Editors, “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Gives Brave Instagram Live About Trauma,” Marie Claire, February 2, 2021, https://www.marieclaire.com/politics/a35388201/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-instagram-live-january-6/.

- 2“Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Opens Up About Trauma - Twitter Search / Twitter,” Twitter, accessed July 29, 2021, https://twitter.com/search?q=Alexandria%20Ocasio-Cortez%20Opens%20Up%20About%20Trauma%20.

- 3Alexi McCammond, “AOC Tutors Dems on Mastering Social Media,” Axios, February 2, 2021, https://www.axios.com/aoc-instagram-social-media-b1caf529-601a-4820-97ab-5be73bc50185.html; William Ramsey, “AOC on Instagram Live: Recounting Jan. 6 Attack Details Draws More than 160K Viewers,” The News Leader, February 1, 2021, https://www.newsleader.com/story/news/2021/02/01/aoc-instagram-live-recounting-jan-6-attack-details-draws-more-than-100-k-viewers/4349979001/.

- 4Fran (@fransquishco) Tirado, “AOC Just Came out as a Survivor of Sexual Assault and Pushed through Her Tears to Seamlessly Draw Comparison to the Systematic Abuse of the Right Wing. *That* Is a Warrior. Thank You, @AOC. 💔 Https://T.Co/AcFSATXrGU,” Twitter, February 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/fransquishco/status/1356428456892850178.

- 5Emma Specter, “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Speaks Out About Surviving Sexual Assault,” Vogue, February 2, 2021, https://www.vogue.com/article/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-surviving-sexual-assault.

- 6Nancy (@RepNancyMace) Mace, “.@AOC Made Clear She Didn’t Know Who Was at Her Door. Breathless Attempts by Media to Fan Fictitious News Flames Are Dangerous. My Office Is 2 Doors down. Insurrectionists Never Stormed Our Hallway. Egregious Doesn’t Even Begin to Cover It. Is There Nothing MSM Won’t Politicize? Https://T.Co/Tl1GiPSOft,” Twitter, February 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/RepNancyMace/status/1356677360507052034.

- 7Jeffery Martin, “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Hid in Bathroom during Capitol Riot and Thought She Was Going to Die,” Newsweek, February 1, 2021, https://www.newsweek.com/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-hid-bathroom-during-capitol-riot-thought-she-was-going-die-1565977.

- 8Nancy (@RepNancyMace) Mace, “.@AOC Made Clear She Didn’t Know Who Was at Her Door. Breathless Attempts by Media to Fan Fictitious News Flames Are Dangerous. My Office Is 2 Doors down. Insurrectionists Never Stormed Our Hallway. Egregious Doesn’t Even Begin to Cover It. Is There Nothing MSM Won’t Politicize? Https://T.Co/Tl1GiPSOft.”

- 9Nancy (@NancyMace) Mace, “I’m Two Doors down from @aoc and No Insurrectionists Stormed Our Hallway... Https://T.Co/PAuLh4Vvam Https://T.Co/XRV4qqY7Qs,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/NancyMace/status/1357310744048640000.

- 10Alexandria (@AOC) Ocasio-Cortez, “@JackPosobiec This Isn’t a Fact Check at All. Your Arrows Aren’t Accurate. They Lie about Where the Mob Stormed & Place Them Further Away than It Was. You Also Fail to the Convey *multiple* Areas People Were Trying to Storm. It Wasn’t 1. You Also Failed to Show Tunnels. Poor Job All Around.,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/AOC/status/1357037568966217728.

- 11Alexandria (@AOC) Ocasio-Cortez, “This Is the Latest Manipulative Take on the Right. They Are Manipulating the Fact That Most People Don’t Know the Layout the Capitol Complex. We Were All on the Capitol Complex - the Attack Wasn’t Just on the Dome. The Bombs Trump Supporters Planted Surrounded Our Offices Too. Https://T.Co/JI18e0XRrd,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/AOC/status/1357025133219700737.

- 12Alexandria (@AOC) Ocasio-Cortez, “@NancyMace This Is a Deeply Cynical & Disgusting Attack, @NancyMace. As the Capitol Complex Was Stormed & People Were Being Killed, None of Us Knew in the Moment What Areas Were Compromised. You Previously Told Reporters Yourself That You Barricaded in Your Office, Afraid You’d Be Hurt. Https://T.Co/N4yoBXAUal,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/AOC/status/1357351611979423745.

- 13Alexandria (@AOC) Ocasio-Cortez, “Wild That @NancyMace Is Discrediting Herself Less than 1 Mo in Office w/ Such Dishonest Attacks. She *went on Record* Saying She Barricaded in Fear. @NancyMace Who Else’s Experiences Will You Minimize?Capitol Police in Longworth? Custodial Workers Who Cleaned up Shards of Glass?,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/AOC/status/1357364139023335428.

- 14Julie Carr Smyth and Christina A. Cassidy, “Female Lawmakers Speak about Rapes as Abortion Bills Advance,” AP NEWS, May 19, 2019, https://apnews.com/article/39d0aec6a7174d77bbf3353d2a8ba709.

- 15Nancy (@NancyMace) Mace, “‘... But to Accuse an Actual Rape Survivor, and One Who Used Her Experience to Vouch for Other Rape Survivors, of Silencing Other Survivors Is Appalling...’ @AOC Attacks GOP Rape Survivor Nancy Mace for Silencing Rape Survivors Https://T.Co/EGyRsLBle2,” Twitter, February 5, 2021, https://twitter.com/NancyMace/status/1357646825461866504.

- 16Tiana Lowe, “AOC Attacks GOP Rape Survivor Nancy Mace for Silencing Rape Survivors,” Washington Examiner, February 4, 2021, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/aoc-attacks-gop-rape-survivor-nancy-mace-for-silencing-rape-survivors.

- 17“Rep. Katie Porter Defends Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez for Capitol Riot Account,” MSN, February 5, 2021, https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/opinion/rep-katie-porter-defends-alexandria-ocasio-cortez-for-capitol-riot-account/vi-BB1dpELS.

- 18“Rep. Katie Porter Defends Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez for Capitol Riot Account.”

STAGE 4: Mitigation efforts

The dispute about AOC’s experience during the Capitol insurrection—and her public responses to critics—inspired a great deal of news coverage from the mainstream media,1 as well as fact-checks published by Reuters2 and Snopes.3

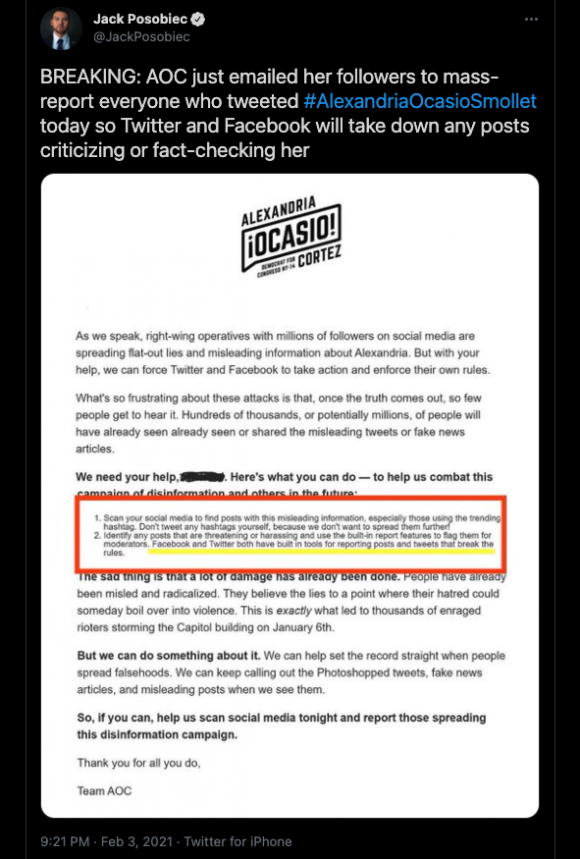

On the evening of February 3, as the #AOCLied hashtag was gaining popularity on Twitter, Jack Posobiec and other critics of Ocasio-Cortez began tweeting screenshots of what appeared to be an official email from the Ocasio-Cortez campaign team, informing her supporters about the hashtag and requesting that they “help us scan social media tonight and report those spreading this disinformation campaign.”4

- 1Lauren Frias, “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Condemned Critics Who Accused Her of Lying about Her Experience during the Capitol Siege,” Insider, February 4, 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/aoc-condemned-people-accused-her-lying-capitol-siege-2021-2; Lydia Wang, “Conservatives Are Now Attacking AOC’s Capitol Siege Story On Twitter,” Refinery29, February 4, 2021, https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2021/02/10294522/aoc-candace-owens-republicans-twitter-capitol-attack-timeline; Graeme Massie, “AOC Hits Back at Claims She Lied about Capitol Assault Ordeal,” The Independent, February 3, 2021, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/aoc-capitol-riot-claims-b1797224.html.

- 2Reuters Staff, “Fact Check: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Did Not Claim That She Was in the Capitol during Siege, nor That Rioters Entered Her Office,” Reuters, February 5, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-factcheck-aoc-instagram-live-video-idUSKBN2A51RK.

- 3Bethania Palma, “Did AOC Exaggerate the Danger She Was in During Capitol Riot?,” Snopes.com, February 3, 2021, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/aoc-capitol-attack/.

- 4Jack (@JackPosobiec) Posobiec, “BREAKING: AOC Just Emailed Her Followers to Mass-Report Everyone Who Tweeted #AlexandriaOcasioSmollet Today so Twitter and Facebook Will Take down Any Posts Criticizing or Fact-Checking Her Https://T.Co/ITsAAUWplt,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/JackPosobiec/status/1357197628677701632; Fiorella (@Fiorella_im) Isabel, “If You Still Don’t Understand AOC Is Controlled Opposition Used by the Dem Party to Rebrand Progressives as the New Liberals Here Is What She’s Focused on Ínstead of Helping People. Https://T.Co/YgmxWK6o5H,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/Fiorella_im/status/1357184339289669632; Ryan (@RealSaavedra) Saavedra, “This Email Is Allegedly from ‘Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez for Congress’ It Instructs People to: -Find Social Media Posts with ‘Misleading’ Info -Not Use Trending Hashtags -Report Posts to the Platforms It Comes after AOC Had 2 Negative #1 Trending Hashtags over the Last 24 Hours Https://T.Co/RSbUgYMhxv,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/RealSaavedra/status/1357238014221512705.

The specific screenshot posted by Posobiec, which featured yellow, red, and black annotations, was reposted to several Telegram channels on February 4,1 including that of Disclose.tv, which has more than 289,000 subscribers as of July 2021.2

Also on February 4, Fox News reported that a spokesperson for Ocasio-Cortez had confirmed the authenticity of the email screenshots.3 It is unclear how many people received this email, but several partisan reported on the mitigation effort, including Independent UK,4 and The Daily Caller.5

The email specifically instructed Ocasio-Cortez’s supporters not to use the hashtags in their own posts. “Don’t tweet any hashtags yourself, because we don’t want to spread them further!” the email read.

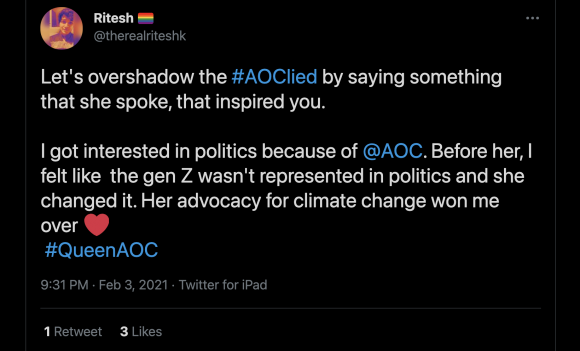

Despite this instruction, shortly after the email was reportedly sent on February 3, many of Ocasio-Cortez’s online supporters participated in a decentralized community mitigation effort to “take over” the #AOCLied hashtag on Twitter. Seemingly unprompted by any campaign organizers, several unverified users began encouraging their (relatively few) followers to post unrelated images, pop culture references, and feel-good messages alongside the #AOCLied hashtag, in order to drown out any disputes of Ocasio-Cortez’s account.

“Let’s overshadow the #AOClied by saying something that she spoke, that inspired you,” instructed one user. “I got interested in politics because of @AOC. Before her, I felt like the gen Z wasn’t represented in politics and she changed it. Her advocacy for climate change won me over [heart emoji] #QueenAOC.”6

- 1@TheWesternChauvinist, “Big Titty Commie Bitches Always Lie. @TheWesternChauvinist Https://T.Me/Disclosetv/537,” Telegram, February 4, 2021, https://t.me/TheWesternChauvinist/7213; @stormypatriotjoe21, “Most Conservatives Aren’t Even on Twitter AOC Fakes Being in Danger Then Puts out a Letter Showing Twitter and Facebook Use Tools to Censor Conservatives It’s Almost like We Are Using Her as a Weapon to Expose (Them) Https://T.Me/Disclosetv/537,” Telegram, February 4, 2021, https://t.me/stormypatriotjoe21/489; @SSG_Cue, “Now AOC Is Telling Her Supporters to Search for and Report Misleading Content.,” Telegram, February 4, 2021, https://t.me/SSG_Cue/285.

- 2@disclosetv, “NEW - AOC Just Emailed Her Followers to Mass-Report Everyone Who Tweeted #AlexandriaOcasioSmollet Today so Twitter and Facebook Will Take down Any Posts Criticizing Her. @disclosetv @disclosetv_chat,” Telegram, February 4, 2021, https://t.me/disclosetv/537.

- 3Michael Ruiz, “Ocasio-Cortez Campaign Urges Supporters to Report Critics to Twitter and Facebook,” Fox News, February 4, 2021, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/ocasio-cortez-critics-twitter-facebook.

- 4Justin Vallejo, “AOC Calls for Supporters to Mass Report Posts to Twitter and Facebook as Fans Spam Hashtag with Pet Photos,” The Independent UK, February 5, 2021, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/alexandria-ocasiocortez-us-capitol-riot-b1797918.html.

- 5Virginia Kruta, “Ocasio-Cortez Enlists Followers To Report Anyone Calling Her ‘Ocasio Smollett,’” The Daily Caller, February 4, 2021, https://dailycaller.com/2021/02/04/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-enlists-followers-report-calling-ocasio-smollett/.

- 6Ritesh 🏳️🌈 (@therealriteshk), “Let’s Overshadow the #AOClied by Saying Something That She Spoke, That Inspired You. I Got Interested in Politics Because of @AOC. Before Her, I Felt like the Gen Z Wasn’t Represented in Politics and She Changed It. Her Advocacy for Climate Change Won Me over ❤️ #QueenAOC,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/therealriteshk/status/1357200048359022593.

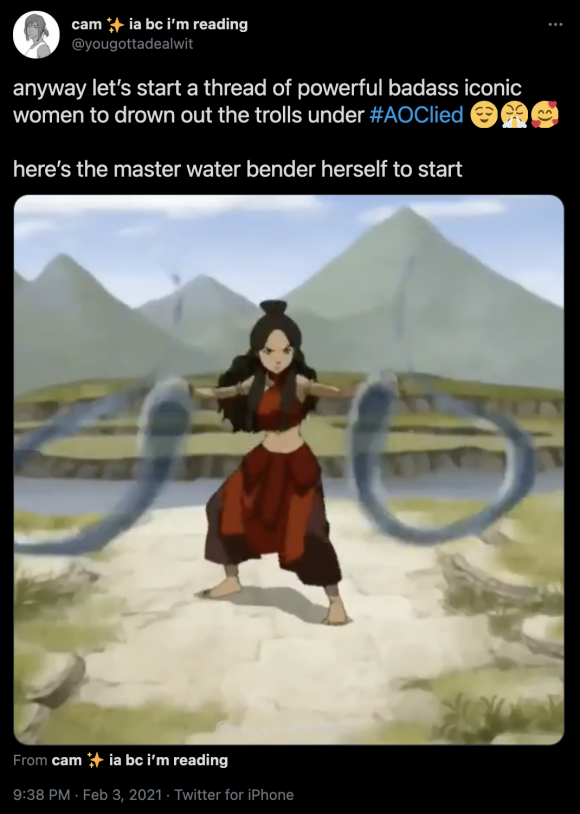

“anyway [sic] let’s start a thread of powerful badass iconic women to drown out the under #AOCLied,” posted another Ocasio-Cortez supporter, alongside a video featuring a character from the Nickelodeon cartoon, Avatar: The Last Airbender.1

- 1cam ✨ ia bc i’m reading (@yougottadealwit), “Anyway Let’s Start a Thread of Powerful Badass Iconic Women to Drown out the Trolls under #AOClied 😌😤🥰 Here’s the Master Water Bender Herself to Start Https://T.Co/IUooX1X89p,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/yougottadealwit/status/1357201742673420289.

“#AOCLied Do you have any fun or cute ACNH pictures y’all?” wrote another AOC supporter, referring to the video game Animal Crossing: New Horizons. “I think this is a great hashtag to share them on~!”1

- 1🐸𓆏Adon+Team Cyberpunk𓆏🐸 (@greaserparty), “#AOClied Do You Have Any Fun or Cute ACNH Pictures Ya’ll? I Think This Is a Great Hashtag to Share Them On~! Or You Can Share Them on My Post. I Bet @AOC Has Some Cute ACNH Pictures Https://T.Co/Ul0Uzxm8ew,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/greaserparty/status/1357230467490189314.

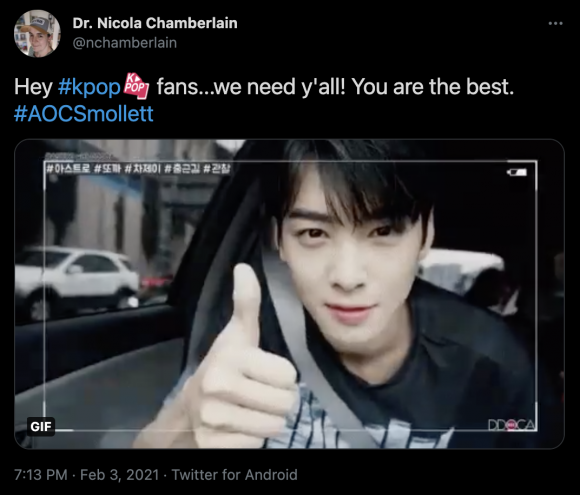

Some users began to call upon K-Pop fans—who have been known to organize and mobilize online around political causes in the past1 —to aid in the hashtag “takeover.”2

- 1Grady McGregor, “How K-Pop Fans Are Wielding Their Organizing Power against Donald Trump,” Fortune, June 22, 2020, https://fortune.com/2020/06/22/kpop-fans-trump-rally-crowd-size/.

- 2Nyxon (@Nyxioto), “#AOClied Have the Kpop Stans Raided This Hashtag yet? If Not Get to It y’all. We Need You Rn,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/Nyxioto/status/1357193288302927874; Dr. Nicola (@nchamberlain) Chamberlain, “Hey #kpop Fans...We Need y’all! You Are the Best. #AOCSmollett Https://T.Co/AVBXqytTVN,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/nchamberlain/status/1357165351008694273; Shamarah (@MsShamarah) Diana 7, “KPOP Stans, We Are Once Again Summoned 🥰 So Enjoy the Aesthetic Queen Ryujin #MIDZY #ARMY #STAYS #ONCES #AOCSmollett Https://T.Co/EuEyZveoCG,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/MsShamarah/status/1357175969828675584; OT Genesis Looks Like a Ninja Turtle (@JamSaidThat), “#AOCSmollett #kpopstans #kpop Can y’all Do That Thing y’all Be Doin,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/JamSaidThat/status/1357185711842226178; Jeanne (@bulmasan) Burch, “#AOClied Time for #KPoP Fans to Take over This Hashtag Https://T.Co/Fy2uSyIZVV,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/bulmasan/status/1357194753830359040; AMs (@chaplin8383), “#AOClied. Yeah, Right. Hit Us with More of Your Heartlessness and Your Hurtful Comments about a Woman Who Is Trying to Help All of Us. #Kpop #kpopstans Let’s Defeat the Hate. Https://T.Co/GnW2IKMfEK,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/chaplin8383/status/1357209002262880256; Ellis (@Ellis_Crane) Crane, “#AOClied Can We #Kpop This into the Ground Please? Educating People on the Layout of the Capitol Complex Doesn’t Seem to Be Enough Tonight. Let’s #Blink Them out of Existence. Https://T.Co/TzWO8gCBP1,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/Ellis_Crane/status/1357224189468446721; Miastarr 7⟬⟭ ⟭⟬ 💛 (@Miastar), “Oh Let’s Bring out the Big Guns Here’s Multi Talented International Superstar Jeon Jungkook Because #AOClied Is Bogus Https://T.Co/4eegUC78v2,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/Miastar/status/1357203710254850048.

As a result, the hashtag quickly became overwhelmed with posts containing gifs and videos of K-Pop stars.1

Meanwhile, other Ocasio-Cortez supporters began posting pictures of their pets or cute animals alongside the #AOClied hashtag, sometimes with encouraging words directed towards the representative.2

- 1Lorraine🦇 (@plaguebabe), “Let Me Just Flood This Political Hashtag with Some Kpop #AOClied Https://T.Co/MXP6JgyZOP,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/plaguebabe/status/1357197126187454465; jo (@@tasteofjoji), “#AOClied Never. Https://T.Co/FeAsXu4XMr,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/tasteofjoji/status/1357183783326408704; Kentucky (@KMegachurch) Megachurch 💜🧈, “#AOClied? Ha Ha Every Time I See the Hashtag I Immediately Think ‘AOOOOO! Lee Chae-Rin!’ Https://T.Co/WJEg83LUb4,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/KMegachurch/status/1357312591316484096; MK (@armymom_bts), “#AOClied Nope She Didn’t. Https://T.Co/HgRNQsU8G6,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/armymom_bts/status/1357177678130995201.

- 2Ellie (@ekl817) Lamkin, “#AOClied Don’t Worry, Girl. We’ve Got Your Back. @AOC Https://T.Co/WmDFj5Mt1b,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/ekl817/status/1357416624500924416; Mychal (@mychal3ts), “I Love the Internet’s Takeover of ‘#AOClied’ with Pets. Bravo 👏🏽 Https://T.Co/VZbG2bICcT,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/mychal3ts/status/1357339216837943299; Cici (@CiciRydaa), “#AOClied Is Trending so I Clicked on It and It’s All Pictures of Peoples Pets. And Who Says the Internet Doesn’t Bring People Together? 🤣 Https://T.Co/5WZ6OZudxV,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/CiciRydaa/status/1357386735848718338; Philippe (@LeftyShifty) Gaulier Farlout Loenclathiclese al Diabli, “@davidmweissman @AOC @IlhanMN @RepSwalwell @JoyAnnReid @Alyssa_Milano @ChrisCuomo @AuthorKimberley @Goss30Goss She’s a Strong, Courageous, Inspiring Truth-Teller. All Qualities That Make the Right EXTREMEly Nervous. Love That Their Hashtag #AOClied Is Getting Flooded with Beautiful Pet Pics. Here’s My Contribution, Queen Victoria. Https://T.Co/NVRxi0QSCn,” Twitter, February 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/LeftyShifty/status/1357547002557530112; Blair 🔺 (@iilluminaughtii), “I See That #AOClied Is Trending Bc People Are Trying to Dismiss Her Sexual Assault Claim. We Stand with Survivors. Here’s Casper for Support! Https://T.Co/D7LJ9xv07d,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/iilluminaughtii/status/1357346962987651074; Monika (@MizPeltz) Peltz, “#AOClied Actually No She Didn’t but Here Is a Pic of My Elderly Beagle with a Puppy Who Wanted to Join Him in His Crate. Https://T.Co/LX7Ua8MHwe,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/MizPeltz/status/1357312616129957890.

The timing and sheer number of tweets posted as part of the community mitigation suggest that Ocasio-Cortez’s supporters may have contributed significantly to the rapidly rising popularity of the #AOClied hashtag, inadvertently helping it push to the top of the Trending list on the evening of February 3.

By the next day, February 4, several news outlets—including Buzzfeed,1 Newsweek,2 and The Huffington Post3 —published articles about the counter campaign, featuring headlines such as, “AOC Supporters Are Flooding The #AOCLied Hashtag With Adorable Pet Photos,” and “K-Pop Fans Hijack 'AOCLied' Hashtag in Defense of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.”

That same day, Ocasio-Cortez acknowledged the counter campaign by tweeting, “Thank you for all your puppy content today!” along with a video of her own dog.

- 1Lauren Strapagiel, “AOC Supporters Are Flooding The #AOCLied Hashtag With Pet Pictures,” BuzzFeed News, February 4, 2021, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/laurenstrapagiel/aoc-supporters-are-flooding-the-aoclied-hashtag-with-pets.

- 2Seren Morris, “K-Pop Fans Hijack ‘AOCLied’ Hashtag in Defense of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez,” Newsweek, February 4, 2021, https://www.newsweek.com/k-pop-fans-hijack-aoclied-hashtag-defense-alexandria-ocasio-cortez-1566730.

- 3Lee Moran, “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Defenders Hijack Insulting Hashtag In The Cutest Way,” HuffPost, 56:16 500, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-hashtag-hijacked_n_601cf1dec5b68e068fbd326c.

STAGE 5: Adjustments by campaign operators

While the original media manipulation campaign mostly waned on Twitter after February 4, TikTok and YouTube users continued to post videos undermining Ocasio-Cortez’s claims in the weeks that followed, and /pol/ continues to discuss her sexual assault claims—as well as her physical attractiveness—on a regular basis.1 2

In July 2021, the #AOClied and #AlexandriaOcasioSmollett hashtags were still being used occasionally on Twitter.3 For example, a handful of users have employed #AOClied while criticizing the AOC’s stance on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.4

On July 27, 2021, the group Project Veritas—well known for its media manipulation campaigns in which its journalists claim to go undercover to reveal liberal fraud or bias and then release edited videos to discredit their targets—attempted to redeploy the manipulation campaign. Project Veritas released what it described as snippets from a CNN documentary that had not yet aired, in which Ocasio-Cortez talked about her January 6 experience and her sexual assault claims. Project Veritas described the video as a “leak,” and pointed out to its viewers that Ocasio-Cortez had compared the insurrection to her alleged sexual assault.5 The timing of this redeployment was likely strategic, given that the Project Veritas video was published on the same day as the first hearing for the select congressional committee investigating the events of January 6.6

The YouTube video was quickly spread by right-wing influencers like Dinesh D’Souza, who tweeted it and uploaded the video to the hosting site Rumble.7 YouTube removed the video, reportedly after being asked to do so by CNN, but clips are still available on various alt-tech sites, embedded in right-wing news sites like Post Millennial,8 and on Twitter. When the post was removed from YouTube, Project Veritas Chief of Staff Eric Spracklen tweeted, “Big tech is colluding with @CNN to take down the #BeingAOC leak / This is as Orwellian as it gets.”9

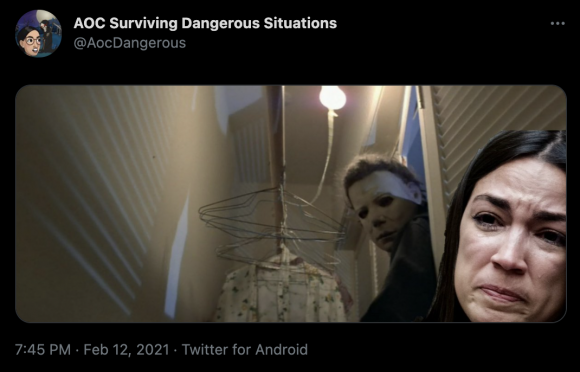

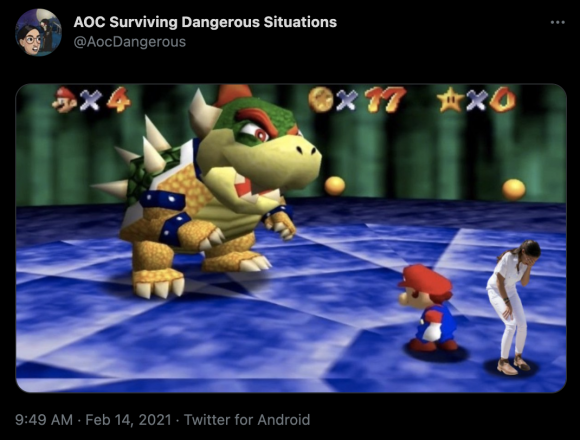

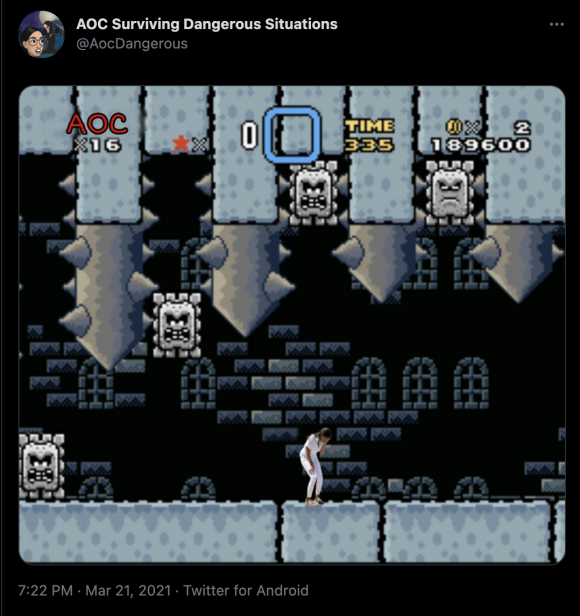

In addition, the manipulation campaign inspired several satirical political cartoons,10 memes,11 and even a crowd-sourced parody Twitter account where users share photoshopped images of Ocasio-Cortez—including the image from the 2018 protest—inserted into scenes from famous horror movies, video games, and other “dangerous situations.”12

- 1Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #315002225,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, April 3, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/315002225/#315002461.

- 2Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #319292303,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, April 29, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/319292303/#319292303; Anonymous, “/Pol/ - Politically Incorrect » Thread #316319851,” 4chan, accessed via 4plebs, April 11, 2021, https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/316319851/#316319851.

- 3Don_Vito 🇺🇸(@Don_Vito_08), “What a Disgrace to All the Constituents of #Queens #Bronx and #NYC #AOC #AOClied #MiddleEastConflict,” Twitter, May 16, 2021, https://twitter.com/Don_Vito_08/status/1393913307774570497; M.Savagefan (@Boabbysam), “I’m Sure @AOC Has Been Crying for Hours. #BidenBorderCrisis #AOClied #AOCcried #KidsInCages #BREAKING,” Twitter, March 27, 2021, https://twitter.com/Boabbysam/status/1375826508078587909; Rob (@rob_rosta) Stanley, “@christineyeargs @AOC AOC Is a L I A R ! ! #AOClied .... Again.,” Twitter, May 17, 2021, https://twitter.com/rob_rosta/status/1394464983975608321; human Intelect (@bleednshiver), “Man These Lefty Bitches Sure Are Scared of @mtgreenee , They’re Sure Talking a Lot of Unsubstantiated, Unverified, Possibly Liable, Covington Grade Bs. Almost as Scared as #AOC to Debate, like She Was of @benshapiro 🐥bok Bok. Oh Yeah, Never Forget #AOClied,” Twitter, May 13, 2021, https://twitter.com/bleednshiver/status/1392802223399202817; dizznmo (@dizznmo2), “@AOC Climate Change Is as Big a Lie as Global Warming Was but Made Made Al Gore a Billionaire, Hmmm? Seems You AOC Are Following in His Footsteps. Shame on You for Pushing Fear to Get Rich! Wake up America, It’s a Big Fat Lie!!#THE BIG LIE #ClimateCrisis #AOClied #ACCOUNTABILITY,” Twitter, May 3, 2021, https://twitter.com/dizznmo2/status/1389275801858809858.

- 4Johanna (@JohannaRose2020) Rose, “Israel Includes Arabs in the Government and Judiciary. Hmmm How Does That Compute with Any Claim That Israel Is an Apartheid State? #AOC #AOClied Https://T.Co/AyXY3KjkC2,” Twitter, May 25, 2021, https://twitter.com/JohannaRose2020/status/1397263994809851906; Geometric Magician (@GeometricMagic1), “@jPra825 @TheBullRun2021 @SenTedCruz Please Explain the below Then. Maybe Stop Having the Media Skew Your Views! Thx! #israel #AOClied #aocsupportsterror Https://T.Co/D6dNOCi7b0,” Twitter, May 25, 2021, https://twitter.com/GeometricMagic1/status/1397299293548126208; Sam (@te99goat), “Which Injustices Are We to Stand up to @AOC? Are We to Tell Israel to Not Defend It’s People, While You Cannot Defend Jews in the United States Who Are Being Harmed. IN YOUR CITY. Don’t Try to Hide It You Are Anti-Semitic. #StopJewishHate #stopAOC #AOClied #JewishLivesMatter Https://T.Co/FS8nYrQNhw,” Twitter, May 25, 2021, https://twitter.com/te99goat/status/1397336110645215235.

- 5“BREAKING: Unreleased CNN Documentary Featuring Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez LEAKED … Compares January Sixth ‘Insurrection’ with Sexual Assault … ‘White Supremacy and Patriarchy Are Very Linked…There’s a Lot of Sexualizing of That Violence,’” Project Veritas, July 27, 2021, https://www.projectveritas.com/news/breaking-unreleased-cnn-documentary-featuring-congresswoman-alexandria/.

- 6Melissa Macaya et al., “July 27, 2021 House Select Committee Hearing on Capitol Riot,” CNN, July 27, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/politics/live-news/jan-6-house-select-committee-hearing-07-27-21/index.html.

- 7Dinesh D’Souza, Project Veritas Releases Undercover Video of CNN Drooling Over AOC (Rumble, 2021), https://rumble.com/vkehtf-project-veritas-releases-undercover-video-of-cnn-drooling-over-aoc.html.

- 8Hannah Nightingale, “Project Veritas Leaks Unreleased CNN ‘documentary’ Celebrating AOC,” The Post Millennial, July 27, 2021, https://thepostmillennial.com/project-veritas-leaks-unreleased-cnn-documentary-celebrating-aoc.

- 9[email protected]🇺🇸(@EricSpracklen), “Big Tech Is Colluding with @CNN to Take down the #BeingAOC Leak This Is as Orwellian as It Gets,” Tweet, Twitter, July 27, 2021, https://twitter.com/EricSpracklen/status/1420066143419699209.

- 10stonetoss comics (stone_toss), “… ,” Twitter, accessed via Wayback Machine, February 4, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20210204150948/https://twitter.com/stone_toss/status/1357344863230955528.

- 11 Madarab, “AOC Riot Liar,” Imgflip, 2021, https://i.imgflip.com/4x2oz5.jpg.

- 12“AOC Surviving Dangerous Situations (@AocDangerous),” Twitter, accessed July 29, 2021, https://twitter.com/AocDangerous. ; AOC Surviving Dangerous Situations (@AocDangerous), “Https://T.Co/ARQsgVwssN,” Twitter, February 13, 2021, https://twitter.com/AocDangerous/status/1360434810611773447; AOC Surviving Dangerous Situations (@@AocDangerous), “Https://T.Co/BM2wu1Kqqq,” Twitter, February 14, 2021, https://twitter.com/AocDangerous/status/1361009589437792257; AOC Surviving Dangerous Situations (@AocDangerous), “Https://T.Co/0aneLSEmCG,” Twitter, March 22, 2021, https://twitter.com/AocDangerous/status/1373822249879408640.

Conclusion:

This case study illustrates the ways in which media manipulation campaigns can be used as tools of harassment aimed at public figures. Memes play a key role in this effort, because they allow a campaign to be adapted for a broader audience and provide fodder for future campaigns. Combined with a deliberate hashtag campaign, this form of networked harassment can carry on long after an event’s initial coverage. In this particular case, despite the news cycle pertaining to AOC’s livestream having long passed, memes about Ocasio-Cortez’s experience on January 6 have continued to circulate on social media, along with the original hashtags used to discredit her account.

This case also demonstrates the power of community mitigation in disrupting the cycle of media manipulation. Whereas organized, top-down mitigation efforts aren’t always effective at mobilizing supporters online or stopping the spread of a specific message, this case shows that organic community mitigation can be a powerful force against manipulation campaigns.

Cite this case study

Kaylee Fagan and Emily Dreyfuss, "Networked Harassment: How a Hashtag Campaign Targeted AOC in the Wake of the January 6 Capitol Riots," The Media Manipulation Case Book, August 12, 2021, https://casebook-static.pages.dev/case-studies/networked-harassment-how-hashtag-campaign-targeted-aoc-wake-january-6-capitol-riots.